The Special Relationship: Parents and Teachers Are Critical Partners in the Work of Social-Emotional Learning

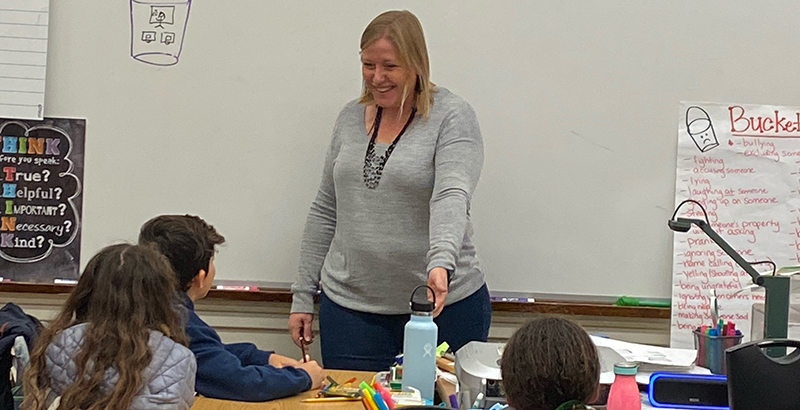

On “meet the teacher night” at the start of school, Franklin Avenue Elementary School teacher Amber Barth leads parents and children through a social-emotional learning exercise that demonstrates the power of finding “commonality with those around us.”

She has her fifth-graders play a bingo game that requires them to find people who share common interests and life experiences. While the kids do this, she instructs the parents to watch for how the kids’ faces light up when they discover that they share hobbies, habits and favorites. Students assume they are very different, Barth explains, so her goal is for them to unearth points of connection. She then lets parents know that she will be counting on them to reinforce these ideas at home, enlisting them as partners from day one.

She remembers what it was like stepping into a system where such partnerships did not exist.

When she first started teaching in Los Angeles Unified School District 15 years ago, Barth said, she felt compelled to change the way her students felt about school. In her former high-poverty Title I school, she could see the demoralization on students’ faces. As soon as she called their names, she said, the students “assumed they were in trouble.”

In that environment, Barth said, phone calls home just turned into parent apologies — not a productive discussion of how to help the students.

So she started looking for “backstory,” she said, the reason for behaviors. Parents are critical to discovering backstory, and Barth could also share her pieces of the puzzle in return. It became about understanding, problem-solving, and empathizing between the parent, the student and the teacher. With a team of coordinated adults seeking to understand and support them, Barth said, students are quicker to accept help and quicker to resolve conflicts instead of getting defensive.

“They know they are not alone,” Barth said.

Who owns the knowledge

Parent-teacher relationships can be challenging for both parties, especially when trying to get to the bottom of a student’s academic or behavioral challenges. When these important adults get locked into a blame game, power struggle or cultural disconnect, it’s the students who lose, experts say.

However, when teachers and parents dig deeply into social-emotional development as partners, research shows that they strengthen the educational experience not only for individual kids but for whole schools as students grow in self-awareness, self-management, social awareness, relational awareness and responsible decision-making.

Those five skills are known as the “competencies” promoted by the growing field of social-emotional learning, or SEL. More schools are adopting social and emotional learning practices like restorative justice circles, “soft skills” training and mindfulness exercises, all aimed to help students succeed and thrive in a complex, interconnected world. However, unlike academic curricula, social-emotional learning is happening all the time — at school, at home, with friends, with teammates — and more research has emerged to support the idea that parents may have a critical role to play.

Some are even hopeful that when teachers enlist parents as partners in specific, highly valued social and emotional work, parents will be more engaged than if they are merely asked to volunteer for events or fundraisers. To not do so, argues researcher Jennifer Miller, would rob teachers of a deep repository of insight into their students, some of which could be key to their success. Parents, Miller said, “are the owners of the knowledge.”

Susan Ward-Roncalli is the social-emotional learning facilitator for LAUSD’s Division of Instruction. Her department places a strong priority on parent engagement when selecting curricula and developing services. Parents of students in grades 4-12 are surveyed on their experience with their school, including their student’s social and emotional well-being while there. Those surveys provide valuable guidance, Ward-Roncalli said: “We don’t want to put our resources behind something parents aren’t [behind].”

Her departments keeps parents informed through newsletters and initiatives that involve at-home conversation starters, but it’s difficult to scale such things or quantify their effectiveness. Social-emotional learning initiatives involve relationship building and systems change that can be slow. Explicit social-emotional instruction is beginning to spread throughout the roughly 486,000-student district, Ward-Roncalli explained, and it has also been integrated into other services, especially special education interventions.

Because social-emotional learning works best when done systemwide, there’s no reason to stop at just parents and teachers, experts say. The New York State Education Department issued a guidance document in March 2019 that pulls custodial staff, administrators, bus drivers and cafeteria staff into the mission of social-emotional learning.

At Franklin, the whole school feels highly relational, says Catherine St. George, a single mother of two daughters. This school year is the first one in 11 years that St. George has not had a child at Franklin, a high-performing K-6 school that serves around 500 students in the Los Feliz neighborhood of Los Angeles. Her daughters were there from 2008 to 2019, and in that time she said she never had a bad experience — or at least not one that she and her daughters didn’t learn from.

When her younger daughter was being bullied by a girl who had once been a close friend, St. George felt her mom instincts kick in. But she knew that if she stepped in on behalf of her daughter, she would likely be in opposition to the other child, a little girl she had known for years. That didn’t feel right. Luckily, St. George trusted Barth, her daughter’s teacher.

She mentioned the situation to Barth, who shared that she’d noticed some tension between the girls. “Ms. Barth is so in tune with her students,” St. George said.

Barth had taught St. George’s older daughter in fourth grade seven years prior, and they had developed such a rapport that St. George knew she could trust the teacher to guide the girls to a mutually beneficial outcome.

“I left a lot of it with Ms. Barth,” St. George said, “It could not have gone better.”

Barth would often share insights about the students with their parents, St. George said, but never in a way that overstepped the boundary between a teacher’s expertise and a parent’s.

‘Cultural humility’

The careful negotiation of sharing but not overstepping is something Miller and her research partner Shannon Wanless have examined in depth. The two study parent-teacher relationships, particularly around teaching social-emotional skills. Miller is the author of Confident Parents, Confident Kids, and Wanless directs the Office of Child Development at the University of Pittsburgh School of Education.

In October, the pair presented some ideas for how this might look during a daylong seminar at the first-ever Social and Emotional Learning Exchange hosted by the Collaborative for Academic, Social, and Emotional Learning in Chicago.

Ultimately, a successful parent-teacher partnership requires “cultural humility” on the part of the teacher, Miller said, because a child’s development is first shaped by their neighborhood, family structure and culture.

Whether teachers are trying to teach explicit lessons around social-emotional learning or incorporate it into their classroom throughout the day, they will be more successful if they know what messages the students are getting at home, the researchers explained.

“We tend to look at parents at receivers of our expertise,” Miller said during the seminar. “If we’re going to develop an authentic partnership, then schools have to be receivers of parental expertise as well.”

Cooperation, self-expression, standing up for oneself and many other interpersonal skills are developed at home first in ways that are “culturally specific,” Wanless said. When teachers know how students relate to their parents and siblings, they can adapt their classroom expectations and instruction.

During the seminar, participants brought up different scenarios where changes in language might help parents see the value of social-emotional learning. Switching from words that sound like New Age or psychological jargon to more familiar terms — e.g., “self-control” as a more mainstream version of “self-regulation” — might help parents realize that they already value the concepts at home.

Others noted that behaviors mean different things in different cultures. For instance, one teacher noted, while eye contact is a sign of respect and attentiveness that many teachers try to instill in their students, in some cultures, particularly in Asia, it is more respectful for children to avoid eye contact with their elders.

Adapting, Wanless said, is different than abandoning. The research is clear that social-emotional development is beneficial for every child, and she sees no need to withhold that from a child altogether just because skills like empathy and emotional expression look different in their home.

While parents are the keepers of their children’s foundational learning, Miller explained, teachers often have more access to scientific, developmental expertise than parents do. Rather than taking a know-it-all approach, she said, their knowledge should make them more nimble and flexible with the curriculum, and able to find a middle ground with parents.

This is where kids get the best results, Miller said. The alignment and common messaging shared by these two important adults helps them feel at ease in the classroom and develop stronger attachment to their teacher. This will help them in all subjects, not just social-emotional learning. Students also see the relevance of what they hear at school when it is echoed at home.

Building these connections usually requires some proactivity, Miller said, but that can be difficult.

“I think it is scary for teachers to reach out to parents,” she said, because what comes back may be skepticism, criticism or daunting challenges at home. Even so, she said, it’s better to make first contact on a positive note than to wait for a tense moment when the stakes are high — like a pending disciplinary action or a failing grade.

Some districts encourage teachers to reach out to parents early in the school year, just to say “Hi,” and to share one positive thing the teacher has noticed about their children. It’s a great goal, Miller said, but very few do it in practice.

That doesn’t mean the chance for a relationship has passed, she said, or that the door is shut on enlisting the parent as a partner.

SEL not like math

The partnership of Bath and St. George began when the latter’s older daughter Aurora started fourth grade in Barth’s class. Mother and daughter were constantly “butting heads,” St. George said. She shared this new and unnerving dynamic with Barth during their first parent-teacher conference, and she was surprised at how much insight the teacher could offer into Aurora’s developmental stage, her unique personality and how best to navigate the choppy preteen years ahead.

“She shared things I never would have thought of,” St. George said. Even better, St. George said, she followed up. The two developed an open line of communication, filling in helpful observations as Aurora moved between home and school.

Social-emotional development is not like math, Wanless points out, where kids learn everything they need to know at school. No curriculum can cover the wide range of skills required for successful relationships throughout life. During the Chicago conference event, researchers emphasized this repeatedly. Teaching and measuring SEL must take context into account.

For example, practicing self-regulation in the classroom is different than doing so with siblings in the family den. While the structure of a classroom should support a student’s efforts to heed the rules, sibling dynamics in unstructured playtime make it much more likely that at some point someone is going to cross a line.

Emotional expression with a teacher asking “How are you feeling right now?” is different than emotional expression when facing down a bully on the playground — in one case it is safe to show vulnerability, and in the other it might be wise to be more restrained.

Miller’s and Wanless’s research shows that parents and teachers can collaborate to cover more of these bases than either can do alone. Working together, Miller said, they reinforce a system of support and cohesion for each other and the children they love.

“There is not ‘them,’” she said. “There is only ‘we.’”

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)