The Path to Excelencia: In Los Angeles, One School Leader’s Mission to Motivate English Language Learners to Succeed

This article was produced in partnership with LA School Report.

Ruben Alonzo’s English learners in his Texas classroom were thriving. He believed in their potential the same way a teacher had once believed in him — a third-generation migrant worker who went on to MIT, Harvard, and Columbia University.

His students were two miles from the Mexican border in Rio Grande, at an independent charter school in the IDEA Public Schools network. Many were not proficient in English, but 98 percent passed their state algebra tests.

“That tells you that regardless of their English proficiency, in the areas of math and science, our English learner students can succeed,” Alonzo said.

Because his life’s passion was to help students with similar backgrounds as his own, Alonzo’s wife, Cynthia, a California native, challenged him to bring his vision to even more students, where historically schools have been failing them.

“We both asked ourselves, ‘Where we can make the greatest impact?’ The answer was Los Angeles, East L.A., and we said, ‘Let’s go!’ ”

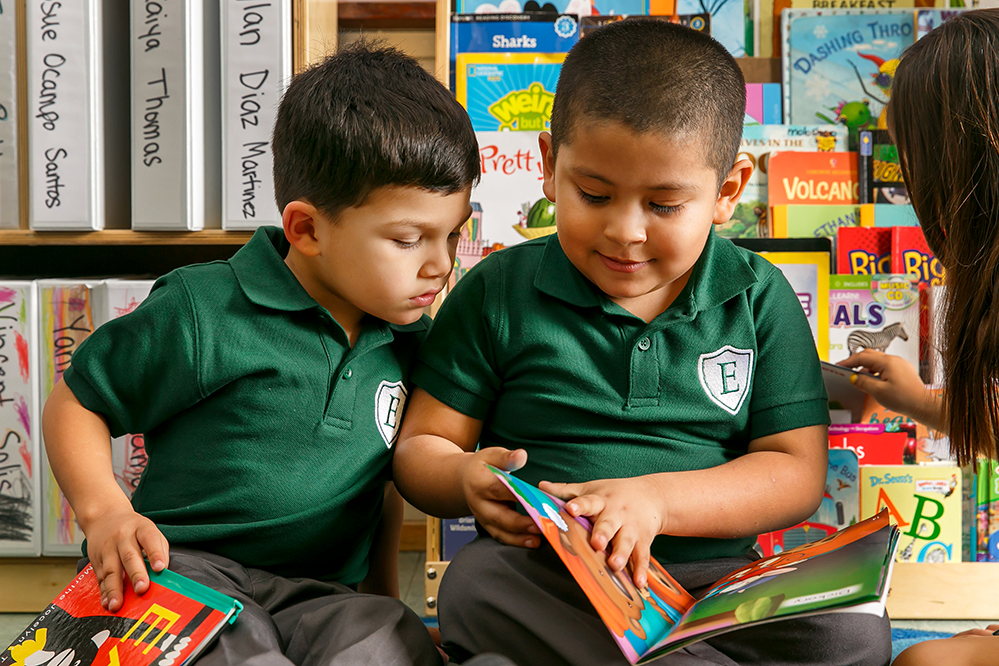

In August, Alonzo will open Excelencia Charter Academy. The independent charter elementary school will start with 120 seats for transitional kindergarten through first grade, with an innovative teaching model for English learners. It will grow to serve students through eighth grade.

“Unfortunately, too many schools here are not proving that their success is possible. We want to prove it, we want to be a bright spot in the city of L.A., in the state of California. We can show ELs can succeed across all subject areas, and just watch us!”

A Vision for Excelencia

Alonzo said his vision for Excelencia grew out of his own experience, working hard in the Texas fields during summers and excelling in school the rest of the year. His father died when he was only 12 years old, and his brother was incarcerated a couple of years later.

Without much guidance about his future, he had decided to join the military after high school, Alonzo recalls, when his calculus teacher, Irma Martinez, said to him, “Absolutely not! You’re not joining the military. You will go to MIT. You can apply to the best school in the world, and I know you can get in.”

“I was an 18-year-old boy, with limited options, whose brother was in prison, whose father passed away, living in poverty, but this one teacher had such a high bar of excellence for me,” Alonzo said.

His teacher helped him fill out and submit his application to the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. When he got in, that was “the moment that completely changed my life, and that’s what Excelencia is about.”

“Excelencia takes that message and that vision that my calculus teacher gave me, and now I want to share it with my students — 4-year-olds, 5-year-olds. When they’re going into first grade, I want them to have that vision that they are going to college, surrounded by adults in school that know that’s the goal,” Alonzo said.

Excelencia will offer a unique “regrouping” model where students, even in the earliest grades, are taught by teachers in different specialties, like in high schools. The two-teacher program is tailored to support English learners.

What’s innovative about Excelencia’s teaching model is that teachers for even the youngest learners will be able to specialize in what they’re best at, said Alonzo, who honed his model the year before Excelencia’s charter was approved, during a Building Excellent Schools training program in urban charter school creation and leadership.

“We will focus on literacy and the best mathematical practices — guided reading, phonetic development, writing, listening, speaking, and cognitively guided instruction. It’s designed to promote small group instruction so students are receiving the individual attention they require on a daily basis, so every teacher can identify the students’ needs and areas of growth.”

A Home for Excelencia

But while his academic vision was crystal clear, Alonzo knew that opening his school on an under-enrolled Los Angeles Unified School District campus wouldn’t be easy to navigate. State law requires school districts to offer unused space to charter schools, but the process is fraught with conflict and called broken by charter leaders and district officials alike.

Alonzo applied for a site in East Los Angeles, where he had approached nearly 1,000 families, ending up with a list of 175 who intended to enroll. He lost many of them in February, however, when L.A. Unified designated classroom space for Excelencia in a totally different neighborhood, at Sunrise Elementary in Boyle Heights.

Most charter schools don’t get their first choice when seeking space on a traditional school campus, said Ebony Wheaton, director of facilities in Los Angeles for the California Charter Schools Association. And there’s no transparency about how L.A. Unified determines which schools to offer, she said. When charters make their requests, “they do it blindly,” without knowing if a school is at capacity or how many unused rooms it has.

However, the district and the charter community are moving toward more cooperation. A resolution passed in April sets up a working group that brings together district, charter, and community representatives to address issues of mutual concern, including the co-location process. It also allows the school board to vote on policy changes to the charter renewal process. Two days after the vote, the charter association dropped two lawsuits it had filed against L.A. Unified regarding its co-location process.

Alonzo said the distance between where he hoped to be sited in East L.A. and the Boyle Heights location is only 2 to 3 miles, but for many families that was enough to look for other options.

Some families have enrolled their children at Excelencia despite the new location. Others turned to Excelencia when they didn’t get into other high-performing schools.

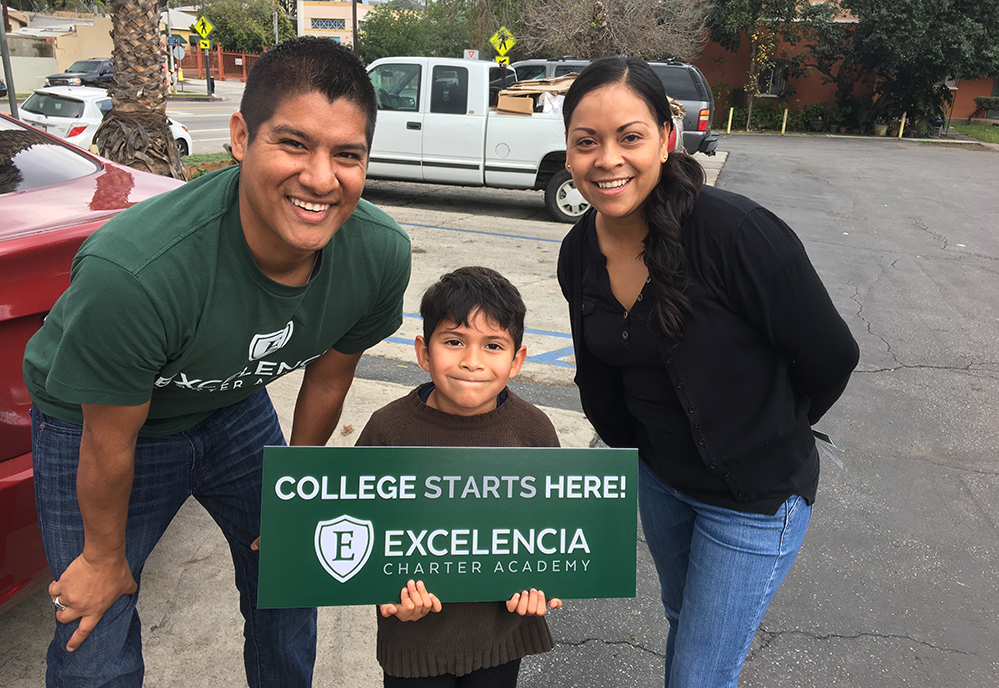

That was the case for Freddy Terrazas. He and his wife had hoped their son could attend KIPP Promesa, but he was placed on a waiting list of 175 students. In the lottery, his son was number 60, and Terrazas gave up hope of getting in. Earlier this year, the six KIPP schools in East Los Angeles had 1,461 students on waiting lists.

“Excelencia became our best option after that,” he said. “All I want is a good school for my son and something convenient for my family. I also liked seeing that Ruben was very connected with us and understood our needs.”

When he met Alonzo and learned Excelencia would be opening next door to his Boyle Heights workplace, he felt it was the perfect match. His son is at a private preschool, and they wanted him to receive a good education at a school with a full-day schedule. Excelencia “offers a full-day program that works perfectly for me and my wife, as we were already worried about him attending a half-day kindergarten program and finding someone to pick him up,” Terrazas said.

Even though his workplace is next door to Sunrise, he said he initially only considered KIPP and the private school his son is attending, but its schedule was problematic for Terrazas. “We were looking for the best schools near home or work, so we only considered KIPP Promesa” and his private school. “We heard from other families KIPP schools were the best.”

Last year, 26 percent of Sunrise students were proficient in English, compared with 40 percent districtwide. In math, 28 percent were proficient, compared with 30 percent in the district.

Pushback against Excelencia

Like many other charters seeking space on district campuses, Excelencia has been targeted by protests by the teachers union, United Teachers Los Angeles, or UTLA. Many charter school faculties are not unionized.

Expressing their concern to Alonzo, some parents have told him that a petition circulating in the community reads, “Sunrise Elementary is in danger! Say no to losing 7 classrooms next school year,” in both English and Spanish. And rumors have spread that Sunrise is at full capacity and therefore Excelencia shouldn’t be allowed there.

The enrollment at Sunrise has dropped from 519 students in the 2010-11 school year to 430 students last year, according to California Department of Education data.

The Excelencia board in a public meeting received a letter this spring saying members of the Sunrise school community “strongly oppose” the co-location because the school will “lose critical space.” The letter, which states that 700 signatures had been collected, was signed “Sunrise Elementary,” but the contact information is for Ilse Escobar.

Escobar confirmed in a phone call that she is not a Sunrise parent but is a UTLA community organizer — information that was not indicated in the letter. A UTLA video shows one of its protests at the school against Excelencia.

“I anticipated some struggles before opening the school,” Alonzo said. “But I never anticipated false information given to parents in the community.”

“The frustrating part is knowing that there are hundreds of kids attending low-performing schools in the neighborhood, whose parents now may have a false impression about our school before they could even hear from us, and that could prevent them from the benefit of the excellent education we’re trying to offer.”

But Alonzo says he’s undaunted. He has a vision in mind, to be a bright spot of success for English learners in Los Angeles, and so he is carrying on.

“My mind, my heart, my operation will always focus on the performance, the progress, and the reclassification of English learners. Unfortunately, in the area of East L.A. and Boyle Heights, if you look at the success rates of ELs, they are failing at alarming rates. In our charter petition, we outlined that we believe our model will change that.”

Alonzo said he expects that about 40 percent of his students will be English learners. “If English learners succeed, all of us are going to succeed.”

Bienvenidos to Boyle Heights

Excelencia will become the third charter elementary school in Boyle Heights.

“There’s just not enough high-performing schools in that [East L.A.] area,” said Myrna Castrejón, executive director of Great Public Schools Now, a nonprofit organization formed to fund high-quality schools. “There’s a sprinkling of high-quality options, districts and charters, but there’s still a high level of concentration of schools that are not meeting the marker.”

Enrollment grew by 20 percent — or 117 students — at the two charters between 2014 and 2017, while the eight district elementaries lost 329 students, or 7 percent of their total 4,330-student enrollment, according to data from the California Charter Schools Association.

In the 10 neighborhoods Great Public Schools Now identified as having the least access to high-quality schools, less than 20 percent of students were on grade level.

“South L.A. remains the area with the highest need, and East L.A. comes next,” including the Boyle Heights section, Castrejón said.

Alonzo now believes the Sunrise campus is where he wants to start building a path for his young students toward academic excellence.

“A school building will not define the kind of education we want to offer. You can be at a multi-million-dollar building or be co-located, but that doesn’t define the leadership, the staff, the vision of the kind of education we want to offer,” he said.

“This is where we want to spend the rest of our lives. I’m building a school for my own future children.”

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)