The paper also found that despite some improvements, charter schools in the state do not outperform district schools on average — indicating that academic performance may not be the driving force behind the white flight to charters.

“Our findings indicate that charter schools in North Carolina are increasingly serving the interests of relatively able white students in racially imbalanced schools,” wrote authors Helen Ladd, Charles Clotfelter and John Holbein of Duke University.

Charter schools in North Carolina originated in legislation passed in 1996 as a compromise between Republicans pushing for vouchers for private schools and Democrats who opposed them. The state capped the number of charter schools at 100, and by 2002, 93 charters were operating in the state, a number that stayed fairly flat for several years.

However, by 2011, spurred in part by federal Race to the Top dollars, a Republican-controlled legislature eliminated the cap with strong bipartisan support and the signature of the Democratic governor. Since then, charter schools have grown rapidly: As of the 2014–15 school year, 153 charters were operating or set to open, according to the paper. Currently, the North Carolina Department of Public Instruction lists 167 charters in the state.

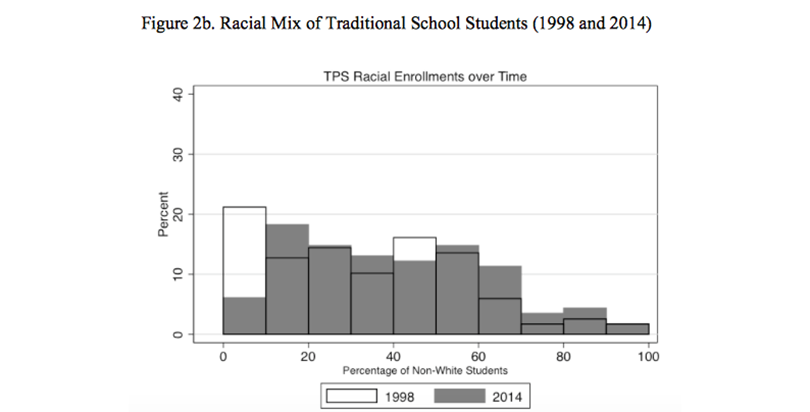

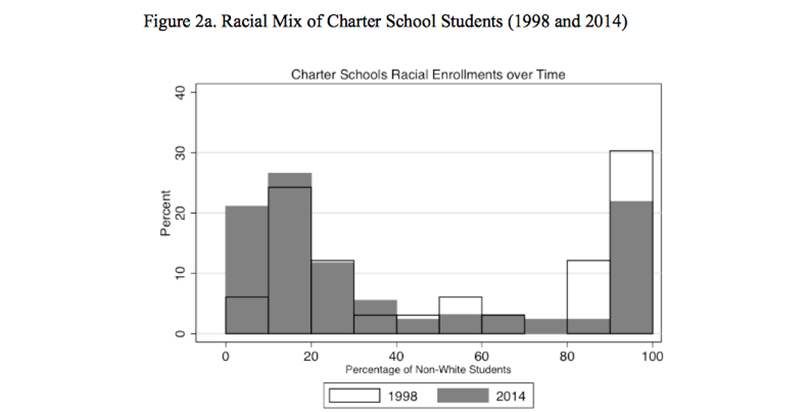

Using data through 2014, the study — originally published as a working paper last year — examined the racial makeup of charter and traditional public schools and found that charter schools are significantly more likely to be composed either largely of white students or largely of non-white students.

For instance, more than one in five charters have student bodies that are more than 90 percent white; in contrast, only about one in 20 district schools has such a large white population. This is a significant shift from 1998, when there were far fewer predominantly white charter schools, though more charters serving mostly students of color.

An important limitation of the study is that it cannot examine the net impact of charters on school segregation in the state as a whole. Co-author Helen Ladd said that because charters make up only a small fraction of student enrollment in the state (3.6 percent in 2014), the net impact on the system was probably relatively small, though likely larger in certain cities.

Ladd said other research she has done showed that when North Carolina students move from district schools to charters, the effect is to create more segregation because white students usually switch from a more integrated traditional public school to a more heavily white charter, while students of color are more likely to move to a charter with more non-white students.

Another study Ladd co-authored found that “schools in [the district of] Durham are more segregated by race and class as a result of school choice programs than they would be if all students attended their geographically assigned schools.”

Charter schools in North Carolina, like elsewhere in the country, are legally required to be open to all students — but that doesn’t mean all of them are open in practice. For instance, charters in the state do not have to provide transportation or subsidized school lunches. In fact, although most charter schools promised to do so in their initial applications, as of 2011 only about one third offered transportation1 and about 40 percent provided federally subsidized school lunches.

“Charter schools that do not offer such services are not likely to attract disadvantaged students, many of whom are racial minorities; instead, they are likely to attract a disproportionately white middle-class group of students,” the Duke study stated.

The research compared charter schools to traditional markets for goods or services under a theory — part of the intellectual foundation for school choice, popularized by libertarian economist Milton Friedman — that suggests firms, or schools, “that are well-run and that satisfy customer preferences will tend to expand or be replicated, while those that are less successful … will not attract and keep customers and consequently go out of business.”

But in some respects, the theory could break down when applied to public education, which is designed to serve a common good. One problem, the study highlights, is that “in choosing schools, parents care not only about the quality of education being offered, but also the mix of students in a school.” This seems to be playing out in North Carolina, as charters appear to be “competing” on the basis of offering white families a less integrated educational environment. This is in line with market theory — but not in a way charter school advocates might have hoped.

Of course, affluent parents can also use housing markets to sort themselves into certain schools designated by neighborhood. But in North Carolina, charter schools may undermine district efforts to ensure racial and socioeconomic integration by, essentially, giving affluent parents another escape hatch.

“In Wake County, which has made a strong and nationally recognized effort over time to keep its traditional public schools racially balanced, children in the mainly white charter schools are much more likely to return to the charter school the following year … than are the children in the few, mainly black charter schools,” the authors wrote. “This pattern provides support for the conclusion that the whiteness of many of the charters is likely to be one of the reasons for their appeal.”

The American Prospect reported earlier this year that efforts to reintegrate schools in the Charlotte-Mecklenburg district had run into “the threat that parents may send their children to private schools or charter schools if their traditional public schools no longer seem desirable.”

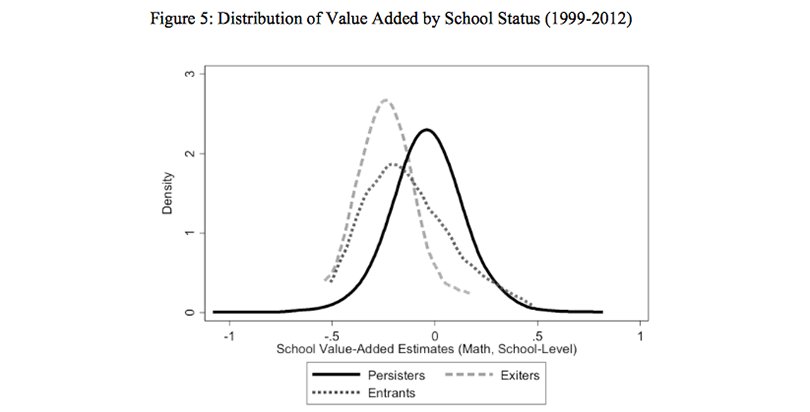

In other respects, though, the market theory in favor of school choice receives more support from the study. The researchers found significant improvement in the quality — as measured by standardized test scores — of North Carolina’s charter schools over time, through 2012. However, charters still perform only about as well as the state’s traditional public schools — and no better, on average — when examining students who move between the sectors.

“Consistent with the prediction of a market model, the North Carolina charter schools have indeed become somewhat more effective over time. It is simply that they started out so weak that the improvements have still not made them more effective on average than the traditional public schools,” the paper said.

Charter schools in the state seem to have improved substantially because many of the lowest-performing ones have closed down, while newer charters have been relatively better. Notably, about one third of schools that shut down did so because of underenrollment, while most of the others closures were due to financial irregularities or mismanagement. The study reports that only one school has been forced to close for poor performance.

The authors hypothesized that a 2006 rule “that required charter schools to delay opening for a year after their charter was approved” may have led to improved performance among new schools.

Lee Teague, executive director of the North Carolina Public Charter School Association, took issue with the study’s results.

He pointed to data showing that across several demographic groups, charter students have higher proficiency rates than district students. But the Duke researchers’ approach is much more sophisticated, since it controls for a greater set of variables that could affect student performance. The study also looks at students switching between charter and district schools.

Teague argued, “The ultimate judges of a school’s quality are the parents. Parents send their kids to a charter voluntarily and can pull them out at any time.” It is true that one important limitation of the study is that it looks only at performance on standardized tests, which are important but do not fully measure school quality. Insofar as parents judge schools by metrics beyond achievement scores, the study may understate (or overstate) charter performance.

Teague also said that by looking at statewide segregation figures, the study does not make fair apples-to-apples comparisons, since charters are located only in certain counties. In other words, if charter schools are more likely to exist in segregated areas, they may simply reflect the demographics of those districts.

But the data don’t bear this out when it comes to white students. Another report examined how the demographics of charters in North Carolina compared with the five nearest traditional public schools: 40 percent of charters enrolled substantially more white students and an additional 21 percent had somewhat more white students.

Teague said that many charter schools did not offer transportation because they don’t receive specific funding to do so. He said all charters were required to create some sort of plan to ensure that transportation is not a barrier to access, though the specifics of what that entails are vague.

As for subsidized school lunches, Teague said that some charter schools did not make them available because the paperwork to participate in the federal program is too cumbersome. He said he had heard of some schools that simply exempted poor students from having to pay for lunch, even if the schools were not part of the federal meals initiative. Other schools did not participate, he said, because they had very few economically disadvantaged kids who would qualify.

When the NAACP called for a national moratorium on new charter schools last summer, the civil rights group cited segregation as a key reason. The Duke study bears out this concern.

In some ways, though, North Carolina’s charter sector looks very different than charters elsewhere. There is huge variation from state to state, but overall nationwide, charter schools serve a greater share of black and Hispanic students, and fewer white students, than traditional public schools. In contrast, North Carolina charters serve a larger proportion of white students and very few Hispanic students.

Another study showed that on average, charter school students nationally start out with lower test scores than traditional public school kids. But in North Carolina, charter students started out much further ahead — more so than in any of the other 26 states examined in the report.

National studies also have raised concerns about segregation in charter schools, but the data are more mixed and differ from place to place.

(The 74: Are Charter Schools a Cause of — or a Solution to — Segregation?)

On the other hand, the performance of North Carolina’s charter schools is fairly consistent with national averages. As in some other states, such as Texas, North Carolina’s charters seem to have improved over time, and like charters nationally, they perform on average at a comparable level to traditional public schools.

North Carolina shows that a market-driven approach to education can have powerful effects, but not always in the way policymakers expect.

There are some obvious potential policies that might flow from the paper’s findings: requiring schools to offer transportation and subsidized lunches, incentivizing (or even mandating) racial and socioeconomic diversity, and reinstituting a cap on charter schools in the state.

Other research raises additional concerns, showing that certain North Carolina charter schools, though by no means all, are out of compliance with nonprofit law and have “hand[ed] the keys of the charter schools over to the for-profit” education management organizations — which can operate with limited oversight.

North Carolina’s likely new governor, Democrat Roy Cooper, wrote on his campaign website, “While some charters are strong, we see troubling trends, such as a resegregation of the student population, or misuse of state funds without a way to make the wrongdoers reimburse taxpayers. We need to manage the number of charter schools to ensure we don’t damage public education, and we need to better measure charter schools so we can utilize good ideas in all schools.”

However, Republicans in the state, who have supported charters, maintain strong majorities in both houses of the legislature.

State policymakers “have the authority to limit the number of entrants or alter the authorization and review processes,” the Duke paper concluded. “The question is whether they will use that authority to assure that the sector serves the public interest and not just the private interests of those who send their children to charter schools.”

1. A more recent survey of charters in the state found that about half reported providing transportation, though only about two thirds of charters responded to the survey. (return to story)

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)