The Mystery of Ryan Walters: How a Beloved History Teacher Became Oklahoma’s Culture-Warrior-in-Chief

The state schools superintendent has become known for his relentless fight against “woke ideology.” Former students call his transformation dizzying.

By Linda Jacobson | October 5, 2023Ryan Walters was one of the most well-liked teachers at McAlester High School.

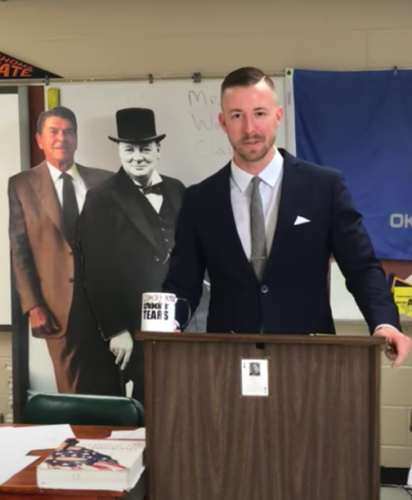

A history teacher and 2016 finalist for Oklahoma teacher of the year, he encouraged vigorous debates on pivotal moments like Roe v. Wade and, closer to home, the forced relocation of Native Americans known as the “Trail of Tears.”

During homecoming week, students gently mocked him on “Dress Like Ryan Walters Days,” sporting his signature slim-fitting suits, skinny ties and color combinations that didn’t always blend well.

Life-size cut-outs of Winston Churchill and Ronald Reagan in his classroom spoke to his conservative values. But if he was a firebrand, none could tell.

“He made us feel validated. He never told us that we were wrong,” said Starla Edge, who had Walters for homeroom, history club and classes each year she was in school. Having come out as queer in eighth grade, she served as president of the school’s Gay-Straight Alliance junior year. But she never felt shunned by her favorite teacher. “I got excited when he went into politics, because I thought, ‘This is my voice.’ ”

Now Edge barely recognizes the man who was elected Oklahoma’s state superintendent last November. In selfie videos from his car, Walters denounces “woke ideology” and frequently accuses teachers of pushing a radical agenda based on atheism, racial justice and gender identity. In a series of provocative statements, he’s called the state’s teachers union a “terrorist organization” and dismissed the separation of church and state as a liberal “myth.”

The relentless focus helped push the small-town teacher who never ran a school or a district into the national spotlight. In July, he spoke along with other conservative luminaries at a summit in Philadelphia held by the right-wing parent group, Moms for Liberty — a platform for several GOP presidential hopefuls.

To Edge and many of Walters’s former students and colleagues, the transformation is dizzying.

“This is not the man that I knew for a large chunk of my life,” she said.

To supporters in blood-red Oklahoma, however, it’s not Walters who’s changed, but the education system that’s gone off the rails.

“We want our teachers to teach … reading, writing and arithmetic,” said Wade Burleson, a retired Baptist minister who ran unsuccessfully for Congress last year and met Walters on the campaign trail. Burleson also wants school prayer and to display the Ten Commandments in every classroom — key tenets of a faith committee Walters formed in June. He called the state chief “one of those rare individuals who will do exactly what he said he was going to do.”

Walters declined interview requests from The 74. But as the 38-year old builds his national profile, he’s coming under increasing scrutiny at home. Following his recent threats to take over the Tulsa Public Schools and a social media post that sparked bomb threats in a neighboring district, Democrats stepped up calls for his impeachment. They cite investigations into his handling of COVID relief funds and a “pattern of inflammatory language.”

Even some Republicans think his rhetoric has gone too far.

“This guy cares more about getting on Fox News than he does about doing his job,” said Republican state Rep. Mark McBride, who leads a House education subcommittee. “Someone has whispered in his ear that he could be governor or … secretary of education.”

Religious upbringing

Walters may not have set out to become a culture warrior, but his values and politics, like those of many in McAlester, reflect a deep religious upbringing.

Nestled between an Army munitions plant and a state prison, the former coal mining center some 91 miles south of Tulsa is a town of 18,000 residents and more than 60 churches.

His father was a bank executive and his mother worked at a local college. Both remain active in the North Town Church of Christ, where he is a minister and she is elementary education director. Like them, Walters attended Harding University, a conservative Christian college in Searcy, Arkansas. His brother and sister also attended.

In a 2021 video honoring him as an “outstanding young alumnus,” Walters, who is married and has four children under age 10, said he chose the school for its “Christian mission.”

Harding students take mandatory Bible classes and attend chapel daily. Its student handbook explicitly forbids same-sex relationships and maintains that “gender identity is given by God and revealed in one’s birth sex.”

It’s an atmosphere that contrasted sharply with the McAlester Walters returned to in 2011.

His eight-year tenure at the high school coincided with greater visibility by the LGBTQ community. In 2015, students at the high school founded a Gay-Straight Alliance. Based on 2016 guidance from the Obama administration, the district also set aside a “family” restroom for transgender students to use.

Brenda Calahan, a retired art teacher who served as the GSA’s first adviser, said many in the community didn’t welcome the developments.

“It was rough for those kids,” she said.

Members of the wrestling team threatened to hurt one of the club’s founding members, setting up a point system for everything from slashing his tires to killing him, said Debra McDaniel, his mother. He left soccer practice one day to find screws stuck in the tires of his car.

The principal at the time told Calahan to remove students’ LGBTQ-themed artwork from a display case near the front of the school. Some students petitioned the school board to disband the club, which still operates today.

Edge remembers overhearing a “few grumpy teachers” complain about the gender-neutral bathroom. Not Walters. Other staff members, she added, made crude references to the GSA, mocking it as “gay shits allowed.” But Walters, she said, “would have shut that down.”

‘There was no black or white’

That view is widely held among former students at McAlester, where Walters taught three Advanced Placement courses — U.S. history, world history and government — and also coached boys basketball and girls tennis.

Former students interviewed by The 74 admired his approachability and sense of fun. When Edge struggled to grasp the finer points of Islam during his AP World History class, for example, he offered to lend her his own copy of the Quran. For another class, he took students to McAlester City Hall, where they took over for the day, playing the roles of mayor and department heads. In a mock council meeting, they voted in favor of allowing residents to own a potbelly pig as a pet.

“When we got done, I was pushing that we needed to do it again,” said Mayor John Browne, a Democrat who is now roundly critical of Walters. “When I found out that he was going to be running [for superintendent], I thought, ‘He’ll be good.’ ”

During classroom debates — with desks pushed to either side of class — Walters critiqued each side’s argument and expected students to back up their claims with evidence.

Shane Hood, another former student, remembers a classroom discussion of the Indian Removal Act, which President Andrew Jackson signed in 1830. Students split over whether the law was racially motivated and unjust or actually benefited Native Amerians. While giving students their say, Hood said, Walters held firmly that white expansionism caused the suffering and death of tribes as they traveled 1,200 miles to what would later become Oklahoma.

“He was much more nuanced,” said Hood, who, like Edge, took all three of Walters’s AP courses. He now attends Oklahoma State University in Stillwater and credits Walters with inspiring him to study political science. “In his classroom, there was no black and white. It was all shades of gray. Now it’s, ‘I’m right and you’re wrong.’”

That reticence in the classroom stood out in a town where 74% of voters chose former President Donald Trump in 2016. Some teachers, Hood remembers, wore MAGA hats in the classroom and let student slurs like “libtard” go unchallenged. But not Walters. Some students even questioned if he was a “closeted Democrat,” Edge said.

Tennis and politics

If his students were ignorant of Walters’s private views, that was intentional, according to those who know him. “No one knew if he was a Democrat or a Republican, and that’s why they loved him so much,” said Chad Waller, a friend and former head coach of the girls tennis team.

After tournaments, Waller remembers the young educator grading papers past midnight. Walters, he said, gets a “bad rap.”

“The man eats, sleeps and breathes education,” he said.

But it was tennis that paved the way for his friend’s foray into politics.

In 2018, Kevin Stitt, a mortgage company owner, became the GOP nominee for governor. At a tennis tournament that year, Walters met Stitt, who was cheering on his daughter, Natalie.

“We kind of struck up a friendship,” Stitt said in the Harding alumni video. After his victory, Stitt invited him to be part of an education working group that advised the incoming administration.

That year, Walters got busy shoring up his conservative bona fides. With no visible prior record of writing for national publications, he gave full-throated voice to views he’d long kept out of the classroom. In three commentaries for The Federalist, an influential conservative journal known for its vetting of federal judicial nominees, he warned of “runaway district courts” that would “undermine the will of the people.” Foreshadowing some of his future positions, he criticized the 2015 Supreme Court ruling establishing a right to gay marriage, saying it demonstrates why justices shouldn’t have final say on constitutional matters.

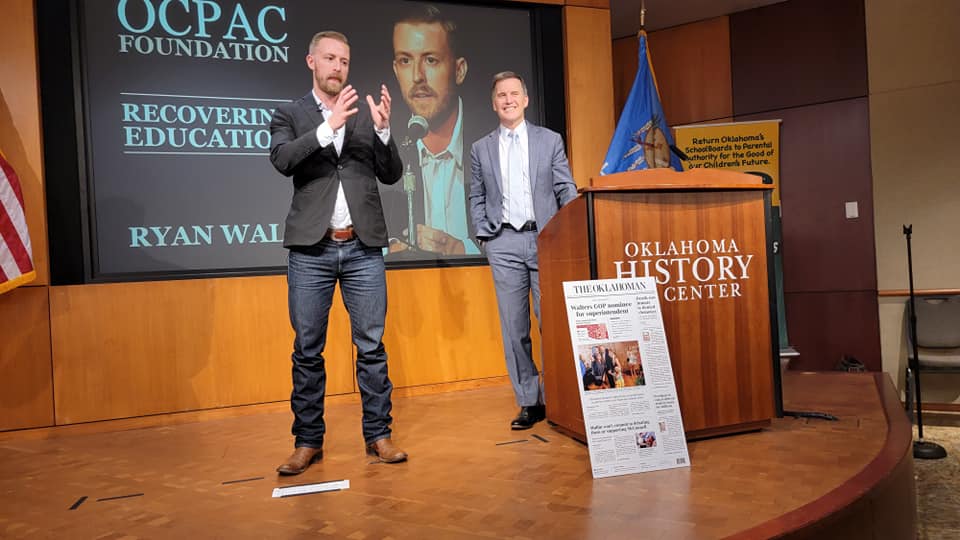

A year later, he landed a job running Oklahoma Achieves, the education arm of the State Chamber, a commerce organization that, like Stitt, supports school choice. The move more than doubled his teacher’s salary. As superintendent, he makes over $124,000.

His rise did not go unnoticed.

“This random, unknown, fresh-faced teacher from McAlester all of a sudden popped into the State Chamber spotlight,” said Erika Wright, founder of the Oklahoma Rural Schools Coalition, a nonprofit that opposes private school choice. “That is the moment where I first questioned ‘Who is this guy, and what’s the bigger plan?’ ”

‘Isn’t that a woke idea?’

At the time, those with more left-leaning views said they could still find common ground with Walters.

In 2019, Rep. Jacob Rosecrants of Norman, a Democrat and former Oklahoma City Schools teacher, began drafting a bill to preserve a “play-based” teaching approach in early-childhood classrooms. He and Walters agreed on the value of recess and hands-on learning.

“He didn’t spout the far-right talking points he does now,” Rosecrants said. Progress on the bill stalled in 2020, and by the time they spoke of it again the following year, Stitt had appointed Walters as his education secretary.

This time, Walters seemed skeptical. “I could hear his tone change, and he began to ask questions … like, ‘Isn’t that a woke idea?’ or ‘How is this not indoctrination?’ ” Rosecrants said. “Why? Because the words ‘social and emotional learning’ were in my bill.”

What happened? The pandemic, for one. The long closures that followed lockdowns in March 2020 mobilized parents, particularly those on the right. School board meetings became battlegrounds over decisions to keep schools closed and kids tied to their laptops. The timing coincided with a right-wing backlash over many aspects of classroom life. Many parents began demanding restrictions on everything from library books on gender and sexual issues to the teaching of racial discrimination in U.S. history.

Social-emotional learning — a decades-old practice associated with teaching kids resilience, empathy and self-control — got caught up in the fight. Some conservatives criticized its focus on identity and called it “too personal” and “too intrusive.”

Oklahoma was not immune. In 2021, it became one of the first states in the country to pass a law prohibiting teachers from offering lessons that suggest students should feel guilt or anguish because of their race. The following year, Stitt signed the “Save Women’s Sports Act,” which forbids transgender athletes from competing in girls’ sports.

With his young daughter Violet smiling and giving a thumbs up beside him, Walters made one of his earliest car videos to celebrate the law’s passage. “We are not going to fall prey to the far left,” he said.

Making the culture war personal

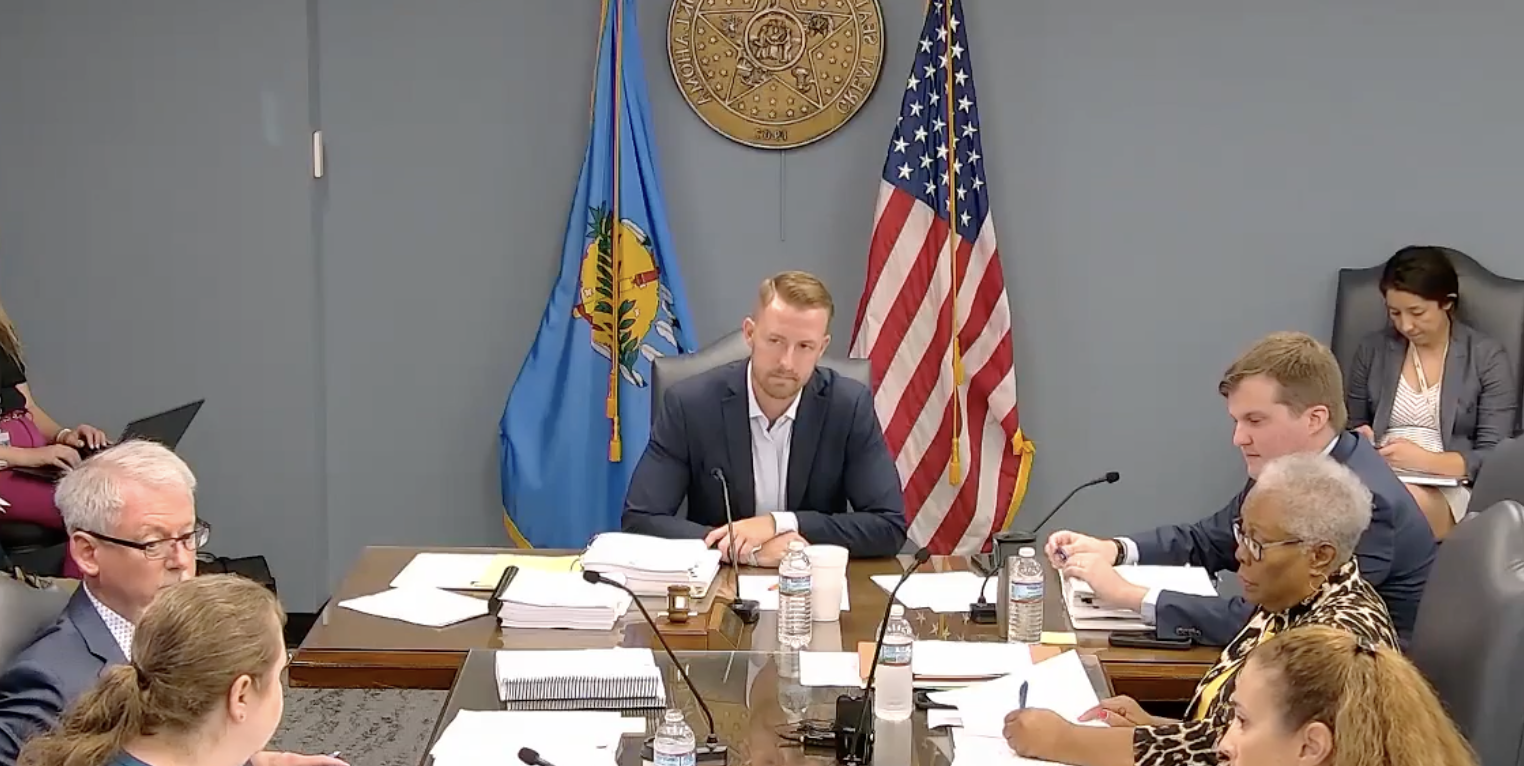

His November election as state superintendent allowed him to step outside Stitt’s shadow. Many hoped taking control of the department of education would mark a turn to more substantive matters, particularly in a state that saw among the largest drops in student performance nationally following the pandemic.

But if anything, Walters doubled down on his rhetoric.

He tried to revoke a teacher’s license after she protested the state’s divisive concepts law by giving students a link to banned books from the Brooklyn Public Library. She later resigned and is now suing him for defamation. More recently, he pressured the Western Heights district to fire a principal who performs as a drag queen on nights and weekends and launched an investigation into its hiring practices.

While other GOP education chiefs occasionally wade into the culture wars, Walters spends most of his time there. He’s established a “granular-level focus” on specific districts, teachers and principals that makes his sharp rhetoric seem personal, said Deven Carlson, a political science professor at the University of Oklahoma.

In a November interview with conservative talk show host Steve Deace, Walters acknowledged taking the host’s advice to make his campaign “a referendum on groomers.” Typically used to describe sexual predators, the term is often employed by conservatives to describe anyone who supports LGBTQ inclusion — potentially minimizing real threats of child sexual abuse, experts say, while demonizing non-heterosexuals.

In May, he dropped a video portraying teachers unions as a threat to children’s safety because of their liberal views on LGBTQ issues.

For Walters, the fight is existential. “The forces that you all are fighting … want to destroy our society,” he said at the recent Moms for Liberty event in Philadelphia. “They want to destroy your family, and they want to destroy America as we know it.”

‘Let’s not tie it to skin color’

The rhetoric has many in McAlester wondering how well they actually knew the man who taught and coached their children for so many years.

Stacy Gorley Williams said her son, Vinny, who played small forward for McAlester High’s basketball team, thought Walters “walked on water.”

Walters’s wife Katie, a therapist, worked for Williams at a nonprofit providing mental health services, and the two often sat together during games. Williams, who chairs the county’s Democratic party and was a charter member of a local LGBTQ advocacy group, said if Walters had given her the impression that he was biased, she wouldn’t have let Vinny play for him.

“I have zero tolerance for people who don’t accept diversity,” she said.

The questions only compound when it comes to Walters’s handling of his area of expertise: U.S. history.

In July, during a Republican meeting at a library in Norman, he appeared to suggest that one of the most shameful events in the state’s history, the 1921 Tulsa Race Massacre, was not racially motivated. A white mob destroyed the thriving Black business district of Greenwood. The violence led to the deaths of an estimated 300 Black people, an episode that was suppressed in Oklahoma for decades.

An audience member suggested the state’s divisive concepts law put teachers in a tough spot: How can they discuss the Tulsa massacre without running afoul of its tricky requirement to shield students from distress?

As a teacher, Walters served on a committee that in 2018 confirmed the episode’s place in state standards, calling it one of many examples of “rising racial tensions” in the 20th century. At the Norman meeting, he insisted the massacre should be taught, but through the lens of individual responsibility.

“Let’s not tie it to skin color,” he said.

He later called the violence “racist” and “evil,” and said the media twisted his words.

Remembering how skillfully Walters handled the lesson on the Trail of Tears, not flinching from its racial dimensions, Hood, his former student, often wonders if Walters believes what he says.

“It’s too much of a transformation in my opinion to be natural,” he said.

@shane.hood Ryan Walters is not who you think he is. #RyanWalters #Oklahoma #Liberal #conservative ♬ original sound – Shane Hood

Branding and performing

For his part, Walters rejects the notion that he’s changed. Responding to a debate question during the campaign, he said, “The reality is my students didn’t know what my political background was.”

“I didn’t tell them what to think,” he said of his time in the classroom. “I challenged them to think.”

Regardless of his actual views, many of them — like his support for funding a religious charter school with public funds — go down well in a state where two-thirds of Republican voters favor candidates who talk about God and Christianity, according to a poll last fall.

Some see his tactics, like the car videos and steady stream of audacious statements, as elements of brand building and securing a base — perhaps in anticipation of a gubernatorial run when Stitt leaves office in 2026.

“He’s very ambitious, and I think that’s what took over,” said Rosecrants, the Democratic representative. “It leads me to believe that all of this is for a bigger purpose.”

Rick Hess, director of Education Policy Studies at the conservative American Enterprise Institute, compared Walters to another high-profile state leader with national aspirations — Democratic California Gov. Gavin Newsom. Last year, Newsom paid for billboards in seven red states promoting California as a sanctuary for those seeking an abortion.

“For an elected chief in blue and red states, unfortunately, the incentives are there to become a performer,” Hess said. “Walters is responding to the incentives, no matter how unhealthy they may be.”

But with his star on the rise, Walters faces mounting problems at home. The state ethics commission fined him for failing to report campaign contributions, including one from the conservative 1776 Project PAC. And two audits criticized his management of a federally funded program to help poor families while he was secretary of education. Over $650,000 in federal relief funds went toward TVs, arcade games and furniture instead of curriculum and tutoring. The Republican state auditor’s office and the FBI are also investigating.

In a podcast with 1776 Project PAC founder Ryan Girdusky, Walters called the attacks against him “absurd.” Dan Isett, department spokesman, said the Democrats’ calls for an impeachment inquiry “represent a direct threat to our democracy.”

Supporters say outrage from the left proves he’s been effective. “This is a man of principle. Has he made mistakes? Possibly,” said Burleson, the retired minister. “But when you are attacked by people unjustly, there’s a tendency to come out strong.”

Confrontation in Tulsa

This summer, he took his most aggressive stance yet against Oklahoma’s largest school system, the 33,000-student Tulsa district, and its former leader Deborah Gist.

He threatened a state takeover after Tulsa officials reprimanded a Moms for Liberty-backed board member who led a prayer at a graduation ceremony. He later accused Gist of failure to disclose how much the district was spending on diversity, equity and inclusion, which she’d described as a ”closely-held core value.”

To prevent the hostile action, she resigned Aug. 22. The state board accredited the district, but “with deficiencies,” noting low academic performance and poor financial oversight. Tulsa’s reading and math scores fell even more than Oklahoma’s overall. But students in the state’s second-largest district, Oklahoma City, lost just as much ground in math, and about 20 school districts rank lower than Tulsa overall.

The intensity of the fight worries observers in other districts, who see in Tulsa a harbinger of where the growing toxicity in education might lead nationally. “We’re now seeing partisan politics become retaliatory politics,” said Susan Enfield, superintendent of the Washoe County schools in Reno, Nevada. “This is ego-driven, reckless leadership.”

As the state board deliberated the Tulsa district’s future, events at the nearby Union Public Schools demonstrated how incendiary Oklahoma’s education politics had become. The district received bomb threats six days in a row after Walters shared a post from a far-right account featuring a local elementary school librarian. The threats continued well into September.

The librarian’s original TikTok video seemed to poke fun at Walters, saying her “radical liberal agenda is teaching kids to love books and be kind.”

Walters, who once got a kick out of reading his students’ mean tweets about his tight pants and patchy beard, apparently didn’t see the humor.

“Woke ideology is real and I am here to stop it,” he wrote.

Disclosure: Walton Family Foundation has provided financial support to Every Kids Counts Oklahoma and its predecessor Oklahoma Achieves, and currently provides support to The 74. Ryan Walters led both state advocacy groups.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter