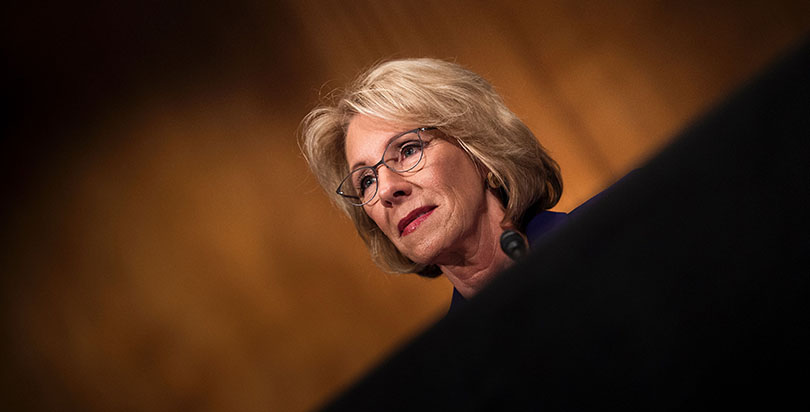

The First 100 Days for the New Education Secretary: How DeVos Stacks Up Against Her Predecessors

Instead, like so much of the lightning-rod secretary’s first 100 days in office, the May 10 speech became a media flashpoint. Students booed throughout her speech; some stood and turned their backs on her. The university president interrupted DeVos’s speech and threatened to mail students’ diplomas rather than continue with the ceremony.

“I have respect for all those who attended, including those who demonstrated their disagreement with me. While we may share differing points of view, my visit and dialogue with students leaves me encouraged and committed to supporting HBCUs,” DeVos said in a statement released after the ceremony.

No small part of the opposition was of her own doing: One of her earliest blunders was the comment that historically black colleges and universities — a consequence of Jim Crow segregation — were “real pioneers of school choice.” (She later wrote a series of tweets backtracking from that sentiment.)

DeVos has seemed to lurch from one PR disaster to another, starting with her late-January confirmation hearing. Yet for all of the chaos and hyped-up scrutiny, the Michigan billionaire and former GOP party leader has actually done very little, observers say, as she approaches her 100th day in office this Thursday — including on her signature issue, school choice.

“There’s just not a lot coming out at this point for us to react to,” said Gary Henry, a professor of education and public policy at Vanderbilt University.

That stands in contrast to Arne Duncan, Barack Obama’s first education secretary, and Rod Paige, who served during George W. Bush’s first term, both of whom had extensive experience in public education and oversaw huge legislative initiatives.

“Relative to certainly all of the commotion, and relative to what one might have expected, not much has happened so far,” said Rick Hess, director of education policy studies at the American Enterprise Institute, a conservative think tank.

The secretary has said her first months in office have “been like drinking from a fire hose in many respects.” The Education Department did not respond to a request for comment. There are no public events on the secretary’s schedule this week.

Her confirmation process became instantly contentious — and earned her a comedic skewering at the hands of Saturday Night Live — when she remarked that perhaps guns would be needed at a school to protect from grizzly bears.

“I do think that her whole confirmation process set her back. It was so bruising. The fact that she had to have the vice president step in and vote for her not only spoke volumes, but I think damaged her politically from the start,” said Elaine Weiss, national coordinator of the Broader Bolder Approach to Education, a project of the liberal Economic Policy Institute.

(The 74: DeVos Confirmed as Ed Secretary After Historic Tie-Breaking VP Vote, Unrelenting Opposition)

The opposition has been unrelenting.

DeVos’s first school visit, to Jefferson Middle School in Washington, D.C., was initially blocked by protesters; she then criticized the school’s teachers as being in “receive mode.” Protesters have continued to demonstrate at most of the 16 school visits she has made as of May 12, including a joint one with American Federation of Teachers President Randi Weingarten.

Generally speaking, she’s made few friends, sometimes even among other school choice advocates. At one point, DeVos criticized Denver’s extensive school choice system as inadequate because it didn’t have private options.

Meanwhile, a public opinion poll released Monday found that most people didn’t know anything about school choice, but the issues of vouchers and other private school choice options that DeVos has championed are increasingly dividing the education reform movement, The Associated Press reported.

To be sure, DeVos, an outside-the-Beltway figure who has pledged to shrink the size of the federal education department while shifting power to the states, does have some support.

Conservatives have praised her hands-off approach to implementing the Every Student Succeeds Act, the new K-12 federal education law.

John Booy, the superintendent of The Potter’s House, a Christian school in Michigan the DeVos family has long supported, said DeVos is exhibiting the same type of leadership as secretary as she did at church and nonprofit organizations in Michigan.

She values listening and building relationships, something she’s done through visits to Education Department staff and to schools, Booy said.

Her policy priorities have stayed the same, too, he said.

“She hasn’t changed her emphasis. Her emphasis for the last 20 years has been to try to empower parents to make the best educational choices for their children,” he added.

Hess said there are some areas where he’d like to see some additional rollbacks by the federal government, but a reprieve from federal activity might not be a bad thing.

“Honestly, given that I’m somebody who thinks the hyperactivity of the Obama years was not all that constructive, I’m OK with the fact that we seem to be looking at a respite,” he said.

DeVos’s lack of activity stands in stark contrast to the two preceding presidents’ first education secretaries — Duncan, who served through much of Obama’s two terms, and Rod Paige, secretary under Bush from 2001 to 2005.

Duncan spent most of his first 100 days in office implementing the massive federal stimulus program designed to stanch the bleeding economy after the 2008 recession. In education, that meant $77 billion in pre-K–12 funding, including what would become the competitive Race to the Top and Investing in Innovation grants.

“That absorbed all the energy, for good or bad,” in the early Obama years, Hess said. “When your parents give you the credit card, it’s easy to cause a big ruckus. We needed to grade on a curve. Even people who are excited about the federal role needed to be very conscious that was kind of a one-time opportunity.”

Paige spent his early days focused on the law that would become No Child Left Behind, one of Bush’s key campaign pledges to close the achievement gap between white and minority students.

Bush unveiled the plan on Jan. 24, 2001, and it was progressing through the Senate by March of that year.

“Things moved very quickly through that period. You could see the stamp of accountability and what [Paige] brought as a former superintendent to try to put accountability forward,” said Henry, the Vanderbilt professor.

Although negotiations surrounding the law would later stall, and a final compromise wasn’t reached until after the September 11 attacks, “they were off and running by the first 100 days,” Hess said.

Comparisons to Duncan, who ran the Chicago Public Schools, and Paige, who served as a university administrator and the superintendent of the Houston Independent School District, highlight another important distinction of DeVos’s leadership that could affect her ability to push through ambitious policy changes. She is not an educator and has not come up through the administrative ranks or ever been in charge of a school system, large or small.

Duncan and Paige also had the benefit of working for presidents who were sharply focused on education and had stronger relationships with Congress than President Trump. His tenure has been marked by endless external crises, like ongoing investigations into Russian meddling in the 2016 campaign, and often-contentious dealings with his own party, even when working toward shared goals, like reforming Obamacare.

Other than a bully pulpit campaign in favor of school choice, most of the actions DeVos and others in the Trump administration have taken on K-12 education revolve around ending Obama-era policies.

So far that has included significantly reducing the federal oversight of states’ ESSA plans and rescinding guidance requiring schools to allow transgender students to use bathrooms and locker rooms matching their gender identity. Spurred by an executive order from Trump, she’ll also begin a broad review of the federal role in K-12 education with an eye toward retracting guidance and regulations that are seen as usurping state-level decision-making.

“She has not done things that would be good for kids and families, and [has] done things that are harmful,” said Scott Sargrad, managing director of K-12 education policy at the Center for American Progress, a liberal think tank that has emerged as a key Trump antagonist.

Generally speaking, liberals criticized her moves to roll back ESSA rules, particularly after the Obama administration put such an emphasis on equity and accountability.

“They’re blowing it on ESSA,” Weiss said.

She also has yet to fill almost all of the key assistant secretary positions, staff who will be critical to proposing new initiatives and advancing policy.

(The 74: With No Senate-Confirmed Appointees, Who’s Helping DeVos Run the Education Department?)

Besides the president’s “skinny budget” proposal, there has been little action on a big school choice proposal. DeVos said last week at an event in Utah that specifics will be coming “in the not-too-distant future,” Education Week reported.

“You get the idea that if they actually were really eager and insistent on moving some of these other pieces, that they might’ve been inclined to move faster to get people in place,” Hess said.

That budget proposal, which DeVos backed, also garnered criticism. Trump proposed cutting $9 billion from the Education Department’s budget for fiscal 2018 while adding $1.4 billion in new money for school choice, proposals panned by Democrats and education groups.

John Helmholdt, a spokesman for the public schools in Grand Rapids, DeVos’s hometown, said the district is “deeply concerned about the current direction of the administration.” DeVos and her husband Dick supported the district financially, and DeVos tutored students there.

Officials weren’t surprised by DeVos’s actions, he said — they had disagreements with the policies she advocated while working in Michigan.

Grand Rapids Public Schools just had their first enrollment increase in 20 years, he said.

But budget cuts, particularly to Title II grants, which support teacher training salaries, and to 21st Century Community Learning Centers, which fund after-school programs, could undercut those gains.

“Our greatest concern is what comes out of Washington has the potential to greatly disrupt our success,” he said.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)