The 74 Interview: Political Scientist Heath Brown on COVID-19 and the Politics of Homeschooling

See previous 74 interviews, including former U.S. Department of Education assistant secretary for civil rights Catherine Lhamon, Indiana educator Earl Phalen and former U.S. Department of Education secretary John King. The full archive is right here.

Since the arrival of the COVID-19 pandemic, millions of parents have been forced into part-time roles as teachers, helping their kids manage online coursework as they juggle professional responsibilities of their own. They are, in effect, participating in a kind of homeschooling.

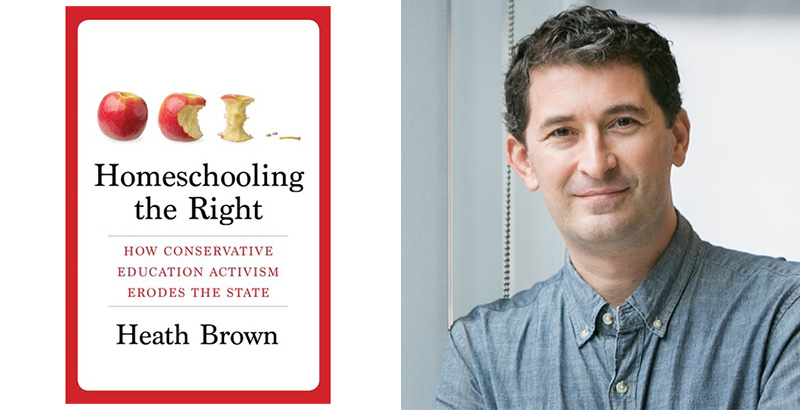

But not entirely, if you ask Heath Brown. A professor of public policy at CUNY’s John Jay College of Criminal Justice, he has spent years studying the history and politics of homeschooling over the past half-century. In his upcoming book Homeschooling the Right, which will be released in January by Columbia University Press, he explores how the issue has been adopted by conservatives as a front in the culture wars — one in which they’ve won consistent victories over several decades.

The ad hoc move to instruction at the dinner table is a gargantuan challenge, Brown told The 74, but there are limits to what parents can learn from committed homeschoolers, many of whom have spent years curating curricula and perfecting field trip itineraries. That’s because so much of successful homeschooling relies on publicly available educational resources — museums, libraries and public parks — that are currently off-limits to students.

In fact, the homeschooling movement and its millions of practitioners play a much more active role in the wider education debate than is generally understood. Homeschool families network, organize and lobby like the veteran constituency they are — especially when they perceive a threat. “The biggest misconception about the homeschooling world is that it’s isolated, cut off from the public conversation,” Brown said.

The willingness of the homeschool community to participate in that conversation has been underscored over the past few months. An explosive debate was triggered in April by the commentary of Harvard Law School professor Elizabeth Bartholet, who has advocated for a “presumptive ban” on the practice and claimed that homeschooled children are in greater danger of suffering abuse or neglect. Giving parents “24/7, essentially authoritarian control over their children,” Bartholet argued, is “dangerous.”

The provocative language, and a planned June conference on the subject at Harvard, drew a furious backlash in the conservative press (one headline characterized Bartholet’s remarks as “an assault on parenting”). The summit was postponed within days, though the stated reason was concern over the coronavirus.

In an interview with The 74, Brown touched on homeschooling’s history, its place within American politics and the change it has seen in recent years. In all, he said, “homeschooling has been as successful a political movement as any other in education policy in the last 30 or 40 years.”

This conversation was edited for length and clarity.

The 74: It must be surreal to have spent years writing a book about homeschooling and then have this emergency necessitate a form of universal quasi-homeschooling in the months before its release.

Heath Brown: Homeschooling in the popular imagination has operated for a long time at the periphery of the educational system. Even in places where homeschooling has thrived, it has remained something that people think of as so different that it’s not part of the wider educational conversation. What COVID has done is raise awareness of the reality of trying to educate students at home, and it has pushed it from the periphery to the center of the conversation about education in this country.

But what millions of families are trying to do now, in coordination with their public or private school, is very different from what parents are doing who made the explicit decision to homeschool back in September. Those families arrived at educating at home in a very different way, so it’s hard to compare what they took on from what the majority of families are doing right now. They look similar, but I’d argue that they’re incredibly different.

What drew you to the history and politics of homeschooling?

I did research in graduate school on the charter school movement, which has its own interesting history. But over time, as I drifted from that study of charter schools, I was fascinated by the contentiousness of the politics of charter schools compared to the lack of policy change that you see in the homeschool world. And I tried to understand why that might be, because from a distance, these two education reforms have a lot in common. They both stand under the umbrella of school choice, but the way the politics have progressed over the last 30 or 40 years has been so divergent. So the aim of the book is in part to understand why what looks so similar has actually turned out so differently.

One difference between the two would be that widespread homeschooling goes back to the 1970s, whereas the first charter school law was passed in 1991. And yet the charter sector has accounted for a greater number of students — something like 6 percent of all K-12 students — in a shorter period of time. Maybe that’s part of what triggered the backlash against charters?

I’d modify that. While homeschooling has its roots in the 1970s, the actual homeschooling policy movement — state legislatures taking this up as an issue — really only goes back to the 1980s. It’s then that you see states beginning to formalize homeschooling and make it acceptable. It had previously been largely non-policy-directed and, in some cases, illegal. But that still precedes the adoption of charter school policies by about a decade.

For a long time, as a result of that, the number of students being homeschooled surpassed the number that were charter schooled, in part because charters weren’t available in all states. It’s only relatively recently that the charter enrollment figures have surpassed the homeschooling figures, and only as we got to the point at which a sufficient number of states allowed homeschooling and the infrastructure was built to permit it.

That’s related to the much more extensive regulatory regime that charter schools operate in compared with home schools. Many charters started as a single grade and grew over time as students progressed in age. Within homeschooling, the regulations have always been so much less involved, and the process of doing it has been much easier for families, and the levels of growth reflect that. We’re now at a point where the infrastructure to do charter schooling is so well developed that their numbers now surpass the homeschooling numbers.

Even the least regulated state for charter schooling still has many, many more requirements on the operators of charters than even the most highly regulated homeschool state. And they’re hard to compare, but on things like testing, teacher qualifications, and subject matter, the charter schools still abide by dozens of regulations — some of them educational, but many non-educational. COVID has made us so much more aware of the public health and civil rights rules that charters are required to abide by.

What do we know about the demographics of homeschoolers? Who makes up this group of families?

The available research suggests that homeschool families are more likely to be white, though that trend has shifted over time, and that world is becoming increasingly racially and ethnically diverse. Twenty years ago, homeschooling was more homogeneously white than it is now. Over time, where it had been largely middle-to-upper-class families doing this, that’s also changed somewhat. Homeschooling has been prominently, though not exclusively, a suburban and rural phenomenon; percentage-wise, more students are homeschooled outside of cities.

So, on average, homeschooling families have been whiter and more affluent overall, though that has changed over the last decade or so.

One factor you didn’t mention is religion. There’s an assumption that homeschooling is largely the refuge of Christian families who want to educate their kids outside the secular school system. Would you say that’s accurate?

From the research I’ve done, the original homeschooling movement in the 1970s and ’80s was a quite varied group of educational thinkers, ideologically and politically. They shared a common interest in parents being given the legal right to educate their kids at home, but they probably didn’t agree on much else.

Over time, that original coalition of libertarians, progressives and conservatives has fractured. And while there are now many parents of diverse political views who homeschool, the political movement behind homeschooling really is situated in the conservative wing of politics. That doesn’t mean there aren’t many liberal or progressive parents who decide to homeschool, but the mobilization and organization of homeschool families is much more prominent on the right.

The evidence suggests that a large portion of families who decide to homeschool do so because of an interest in infusing religion or morality into the curriculum. But it’s not universal, and there are many homeschoolers whose motivations are primarily pedagogical or stem from other reasons within the family. The universe of parents who homeschool is more varied than people understand. The universe of vocal advocates is more homogenous; it’s dominated by conservative groups.

Because homeschooling is a fairly small phenomenon, and perhaps because it’s not well represented in popular culture, it seems poorly understood. Would you agree that there are a lot of misapprehensions out there?

The biggest misconception about the homeschooling world is that it’s isolated, cut off from the public conversation. In fact, what I’ve observed is that homeschooling families are closely connected in strong networks, supported by hundreds of organizations across the country. They’re also very politically energized. If there’s an issue that might tangentially affect homeschooling law in a state, parents are really eager to voice their support or opposition.

I’d attribute that mainly to the effect of local, state and national organizations that have recognized that, though small in number, the motivations of this community makes their voice much louder than their numbers would suggest. And that’s the key misperception: that this is a community that educates at home and remains at home. That isn’t true either pedagogically or politically.

Some of that political vigilance seems to arise from a conviction that homeschooling is a besieged movement, and detractors are trying to curtail the rights of families. Is there a kind of organizational defensiveness at work there?

One thing I’ve observed is that homeschooling becomes for many a prominent part of their identity. And a part of that identity is the perception of a threat, or a sense that the freedom to take this unconventional approach is potentially going to be taken away. That wariness of an attack is part of the identity of homeschoolers, and as a consequence of that, threats and attack appear at the horizon in some cases when they’re not actually there. There are countless cases of legislators introducing bills that probably wouldn’t ever affect how families homeschool their children, but the benefit of the doubt is rarely given, and even the smallest potential of impact on homeschooling is perceived as more significant.

That all goes back to the identity that’s been formed around what it means to homeschool. And it hasn’t always formed organically — it’s been developed by many of the organizations that have helped to serve homeschool families in a variety of ways. Those feelings of independence and liberty are bound up in what it means to homeschool, and they can sometimes lead to overreactions to what might not be an actual threat.

One manifestation of that dynamic has been the huge controversy over the work of Harvard Law School professor Elizabeth Bartholet, who has mused about banning homeschooling. How do you view that dust-up?

The planned conference and the associated article in Harvard Magazine presented homeschooling in a way that sounded inaccurate. But the incredibly loud reaction to the conference seemed, to me, an even greater overreaction. What you’d take away from the critics of this conference is that homeschoolers have been under attack, and that they’ve long been the political losers of the culture wars; they’ve lost more ideological battles than they’ve won, and this conference was further evidence that elites are out to get them.

The political history of this suggests anything but that. There are few examples of homeschool policies reverting back to what they’d been previously. There are few battles that the homeschool communities have lost, and there’s been good reporting of the fear legislators have of even stepping close to homeschooling laws or policies. For the last few years, the homeschool community has been a repeated political winner. They have been much more successful than the advocates of charter schools. On issues like caps on charter school growth, state laws have frequently moved from deregulated to more regulated. This has happened across the country frequently when it comes to charter schools, but it hasn’t been the case with homeschool policies, which have mostly become more supportive and made it easier to homeschool.

For that reason, the reaction of advocates of homeschooling — that this conference is, yet again, an attack on what homeschooling is all about — is somewhat overblown. Homeschooling has been as successful a political movement as any other in education policy in the last 30 or 40 years.

It does seem as though homeschooling doesn’t have many natural opponents, perhaps because the perception of threat is asymmetrical: Stakeholders in the traditional school system — families, teachers, elected officials — often view charter schools as a unique danger to public schools. But homeschooling is seen as a much smaller phenomenon unfolding in red states somewhere else.

There hasn’t been an organized constituency in opposition to homeschooling since the early 1980s. Certainly there are groups that are not in favor of homeschooling, and the Democratic Party has never advocated for it, but it’s never been a big part of their agenda. That’s very unlike charter schooling, where you had prominent Democrats and Republicans advocating for charters until the consensus sort of broke down recently.

Most of these political battles have been one-sided, and few of the powerful organizations that have opposed charter schooling have opposed homeschooling.

There were some specific worries laid out in Bartholet’s article. One was that homeschooled kids are sheltered from social engagement and democratic values. The other suggested that they’re more vulnerable to abuse at home, without teachers as outside adults watching out for them. What do you make of those claims?

I can’t speak to the abuse dimension of this — it’s just not an area where I have enough expertise. But the claims about homeschooling hindering civic development aren’t reflected in the available research. The available research might not be perfect, but it definitely doesn’t suggest that children who have been homeschooled vote less, or participate in politics less, or are civically minded to any lesser extent than students who have attended public or private schools. The evidence is pretty convincing that, if anything, they’re slightly more involved.

With that said, it’s true that the institutional checks we have in place for public schools, including democratically elected school boards, are not in place for home schools. Whether those checks are working is another question, but it’s clear that homeschooling works outside the small-d democratic institutions that have been in place for public schools for going on 150 years. But there’s no evidence for any consequences from that for homeschooled students. They appear to participate in politics, they’re aware of the civic life outside their homes, and they’re connected socially with other families.

Now, it may be that the circles they operate in are closed in some ways to other families, and racial and ethnic patterns of segregation in neighborhoods may mean that they’re isolated in some ways. But that’s also true of public schools, which are prone to high levels of racial and social segregation as well.

You mentioned that there’s been a significant conservative activist tendency within homeschooling. How has that manifested in the past?

From the very early days, there were influential national political leaders who have been connected to homeschooling and seen it as integral to a larger conservative political movement. They don’t make up the whole universe of people interested in homeschooling, but it’s pretty clear that there were several conservative intellectual leaders who had a national platform and were connected to homeschooling.

Over time, that has led to candidates turning to homeschooling families to participate in elections. One of the first and most prominent was when George W. Bush was running in 2000, and there was an organized effort to rally homeschool families to support his campaign. That’s continued over time, and there’s been a tradition in the Republican Party, especially in Iowa and other early presidential states, to organize homeschool families that are conservative to go out and knock on doors. That happened prominently in Mike Huckabee’s Iowa campaign in 2008, it continued with Michelle Bachman four years later, and you saw it with Ted Cruz in the last election.

Conservative homeschool families have been eager to participate, and though there hasn’t been a prominent Homeschoolers for Trump movement, I’m very curious whether such a movement will form during the 2020 campaign.

With the exception of Bush in 2000, those were all pretty recent campaigns. Were those political currents there earlier, at the emergence of the homeschooling movement?

Phyllis Schlafly, who had such a long, important role in the conservative movement, was an advocate of homeschooling for a long portion of her career. She saw it as an important part of her agenda. She made those arguments through her longstanding newsletter and in public speeches. So she’d be a clear example of someone with global name recognition who was advocating for homeschooling long before it was considered significant. In terms of the star appeal of national advocates, it’s hard to think of anyone more prominent than Schlafly.

And if you look at priorities that have been embraced by American conservatives, you’re hard-pressed to find another issue where they’ve been as successful. School prayer has ultimately been a policy loss. For decades, the Right has lost the culture wars on LGBT issues. Though they’ve made some gains recently, they’ve largely lost battles over reproductive rights. Homeschooling has been perhaps the only consistent area of policy victory for the conservative movement. That’s in part because it’s remained somewhat under the radar, but also because there hasn’t been organized opposition in the way that there has been on school prayer and abortion and marriage equality.

What can most parents, newly forced into a kind of de facto homeschooling by COVID-19, learn from those who have been doing it all along?

Unfortunately, there’s less to be learned than you might think. In part, that’s because homeschoolers have generally used their communities as learning laboratories. They’ve relied on local libraries, museums, trips to nature, and generally used their communities as classrooms. That lesson will be lost on every family that is forbidden from going to libraries or community parks because of the restrictions put in place to keep people safe. So one of the cruel ironies of this period is that those things that have made homeschooling attractive for the last forty or so years are, in some ways, inapplicable now. It’s impossible to use the great resources that are available in places when they’re shuttered.

The other part of this is that, for the vast majority of homeschool families, there is a parent who is dedicated full-time to providing education in the home. This isn’t possible for most families now, who are trying to maintain work at home and simultaneously educate their kids. I don’t think there’s a homeschool family in the country that would recommend that arrangement, and it’s obviously a very, very difficult for every family attempting to do that right now. Even with school and teachers trying to provide help through technology, the vast majority of the burden of moving education along is falling on parents. There are just very few models to turn to.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)