Texas AFT Email Reveals ‘Dirty Tricks’ Campaign to Sabotage District/Charter Partnership, Oust Superintendent

In the run-up to the El Paso school board’s November meeting, the teachers union circulated a questionnaire to several people who had been nominated to fill a vacant seat on the board. As one might expect, most of the questions went to where the would-be board member stood regarding things that matter to the union.

No. 4, though, diverted: “It is very likely you will be participating in a superintendent search in the next eight to 12 months. What are your professional (technical), ethical and priority expectations of a superintendent?”

The notion of a superintendent search likely caught the candidates by surprise. In January, Superintendent Juan Cabrera signed a new, five-year contract that included a $45,000 raise approved by a pleased school board, bringing his annual pay to more than $348,000. He’s supposed to serve through 2022.

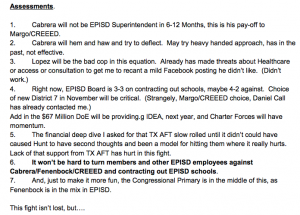

The questionnaire is one of two El Paso Federation of Teachers documents obtained by The 74 that suggest the union, one of two that represent teachers in the 60,000-student district, hopes to put Cabrera on the rails. The document outlines a number of tactics to block any possible future partnership between El Paso Independent School District and charter schools.

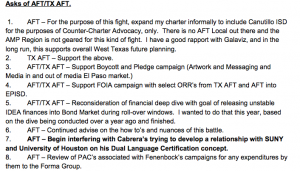

Sent by union president Ross Moore, the email asks the national American Federation of Teachers to “begin interfering with” the superintendent’s relationship with the universities training El Paso’s in-demand, dual-language teachers, to cause problems in the bond market for the nonprofit IDEA Public Schools charter network and to “turn members and other EPISD employees against Cabrera.”

“None of the teachers I know would support this,” says Cabrera. “I want state and national [AFT] leadership to come to the table and show me there’s a path forward, because under this leadership, I don’t see it.”

Moore did not respond to requests for comment, nor did Texas AFT President Louis Malfaro or Secretary-Treasurer Ray McMurrey, who were copied on the email.

AFT President Randi Weingarten, however, defended the missive.

“It shouldn’t be surprising that our members and our affiliates are doing everything they can to fight back against the attacks on public education,” she said in a statement to The 74. “We know from news articles and their own comments that [Education Secretary] Betsy DeVos, the Koch brothers and their ilk are running campaigns in D.C. and across the country to defund public schools, attack unions and turn education into a commodity. Our leadership in El Paso is standing up for kids and teachers and the great neighborhood public schools they need.”

In the email, Moore himself describes his union work in a district with a reform-minded superintendent as “a textbook exercise in damage control … Tap-dancing on a razor blade while juggling hand-grenades.”

The documents have surfaced as the El Paso district is finally closing the door on eight years of turmoil that included an academic cheating scandal that brought criminal charges, a state takeover, and a wholesale change in leadership.

A campaign to destabilize the district threatens hard-won progress, says Dori Fenenbock, who resigned as school board chair in August to run for Congress.

“It has taken years and years of very hard work to turn this district around, and we have done it,” says Fenenbock. “To have the leadership of our teachers organization knowing this, knowing how hard we have worked, trying to destabilize the district for purely political reasons is unacceptable.”

The overarching goal described in the email is to stop the expansion of public charter schools in greater El Paso, which Moore warns “will eviscerate from west to east” the area’s “Big Five” traditional school districts.

Right now, 2 percent of El Paso’s school-age children attend charter schools, the lowest percentage of any large Texas city. Civic leaders have launched a push to open new charter schools in the area.

In September, the three-year-old Council on Regional Economic Expansion and Educational Development (CREEED) hosted an education summit as part of its effort to attract charter schools to the area. IDEA Public Schools and Harmony Public Schools are among the networks that have begun opening charter schools in El Paso, a city in far western Texas on the U.S./Mexico border.

The organization also announced that it had raised $20 million, $12 million of it a new gift from the Hunt Family Foundation, to support both the opening of new charter schools and district efforts to prime its teacher pipeline, including a scholarship fund for teachers to obtain master’s degrees to enable them to teach college-level “dual credit” classes to students still in high school.

CREEED’s CEO is Richard Castro, a Hispanic business leader who owns 21 McDonald’s in the El Paso area. A former elementary school teacher, Castro founded one of the country’s largest college scholarship programs for Hispanic students, awarding more than $22 million since 1985.

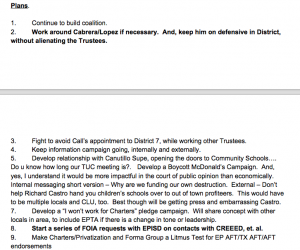

In his email, Moore pushes for a boycott of Castro’s fast food restaurants.

“Develop a Boycott McDonald’s Campaign,” he wrote. “And, yes, I understand it would be more impactful in the court of public opinion than economically. Internal messaging short version – Why are we funding our own destruction. External – Don’t help Richard Castro hand you children’s schools over to out of town profiteers. This would have to be multiple locals and CLU, (Central Labor Union) too. Best though will be getting press and embarrassing Castro.”

In addition to alerting state and national union officials to CREEED’s philanthropic effort, Moore’s email contained a link to a news story in which Cabrera said he is open to partnering with a nonprofit charter management organization such as KIPP to create in-district charter schools, a model that has helped to increase student achievement in Denver and some other large urban districts.

Cabrera was hired four years ago to lead the district out of a period of upheaval that began in 2009, when staff first complained that cheating on tests was taking place in some schools. In August 2011, then-Superintendent Lorenzo Garcia was arrested by the FBI on suspicion of steering a no-bid contract to his mistress. Ten months later, he pleaded guilty both to fixing the contract and to artificially inflating student test scores to game the federal school accountability system. He was sentenced to 3½ years in prison and served 11 months.

Chastising district leaders for their “utter disregard for the needs of students,” in December 2012, the Texas Education Agency stripped the El Paso school board of its power and appointed a board of managers to take its place. In 2015, the state returned control of the district to a local, elected school board. In June of this year, a mistrial was declared in the prosecution of five other administrators implicated in the cheating scandal, although prosecutors are pressing to retry the case.

Cabrera, an unconventional superintendent who taught before practicing education law, was hired in September 2013. The city’s schools lag behind state averages in academic achievement and graduation rates, and two-thirds of graduates need to repeat basic high school courses in college. The cheating rendered student performance data unreliable, but Fenenbock says board members are satisfied steady progress is being made.

Cabrera’s tenure also has attracted scrutiny. In August, the El Paso Times published a lengthy examination of his decision to hire a $1,500-a-day consultant who, among other things, referred the district to a company the consultant used to work for that was looking to handle the district’s $669 million bond issue. Cabrera defended the consultant’s hiring, say the district’s administrative staff did not have the needed capacity.

The paper also reported the district spent $90,000 on Cabrera’s travel from January 2016 to March 2017, far more than other area school chiefs. The superintendent countered that his contract requires him to network on behalf of the district in the interest of rebuilding its damaged reputation.

Last year, the state declared El Paso an innovation zone, giving Cabrera the freedom to try new strategies. Initially on the record opposing charter schools, last summer he said he supported the schools if they were part of the district.

In-district chartering is also favored by El Paso businessman Woody Hunt, whose family foundation has given away $52 million since 1985, including providing major funding for CREEED.

“CREEED’s intent is to work with the school board and the traditional district,” he says. “We would love to see them diversify their choice offerings by including some high-quality charters in the district. I think there’s a path forward that could be productive if everyone is willing to work together for the same outcomes.”

Like Cabrera, Hunt would rather EPISD oversee the charter schools. “The preference would be if that choice were within the traditional district,” he says. “It takes away the issue of charter schools taking money away from the traditional district.”

In-district charters often have freedom from provisions in union contracts that constrain how traditional schools are staffed and run. In some communities, their teachers may not elect to join the union. Moore’s federation is one of two unions present in El Paso, which is located in a right-to-work state. Because of this, labor disagreements that would be resolved by formal processes in other states often play out in the court of public opinion in Texas.

Moore’s email circulated at a crucial juncture, says Fenenbock. “He mentions one of the ways to destabilize the district is to drive a wedge between the board and the superintendent,” she says. “That’s purely about power and has nothing to do with how you help children learn.”

Fenenbock is particularly concerned that the district’s effort to train enough teachers to offer every student bilingual services might be jeopardized. Dual-language instruction is a central piece of the district’s innovation plan, put together last year by a committee that included Moore. Some 83 percent of El Paso students are Hispanic, 65 percent are economically disadvantaged, and 26 percent are English language learners, according to school district data.

Both Spanish- and native English-speaking families asked the district for the bilingual, bicultural programs, she says: “They recognize that one of the strengths of El Paso is that we have the largest bilingual workforce in the Western Hemisphere.”

Traditionally, schools have focused on teaching students who speak another language enough English to keep up in a typical class. In dual-language schools, native speakers of different languages — in this case Spanish and English — are taught in a fully bilingual environment.

The approach has been shown to have what researchers have called “cognitive magic,” forging connections in the brain that contribute to greater literacy and other academic achievement. Student test scores in the dual-language programs Cabrera opened in El Paso are 30 percent higher than for similar students in other programs, Fenenbock says.

Because teachers trained in dual-language instruction are scarce, Cabrera says he hoped to partner with other large districts, including Houston and New York City, to create university programs to train them.

“We’ve had people come back from charters and private schools to enroll in our dual-language programs,” he says. “We’re getting a lot of positive feedback.”

In addition to throwing a wrench in the district’s plan to expand dual-language offerings, harming the university relationships in question would deprive presumed union members of dual-language training, Fenenbock notes.

“On the one hand, they purport to support those teachers,” she says. “On the other, they are taking steps to directly undermine them. It just makes no sense.”

In the email, Moore also discusses researching IDEA Public Schools’ funding “with goal of releasing unstable IDEA finances into bond market during roll-over windows.”

“The financial deep dive I asked for that TX AFT slow rolled until it didn’t could have caused Hunt to have second thoughts and been a model for hitting them where it really hurts,” he wrote. “Lack of that support from TX AFT has hurt in this fight.”

IDEA schools are among the highest performing in Texas, boasting a 100 percent college acceptance rate for graduates. Almost all of its 24,000 students are low-income Latinos living in Austin, San Antonio, or the Rio Grande Valley. The network plans to open its first two schools in El Paso in the 2018–19 school year.

IDEA founder and CEO Tom Torkelson says he is unclear what financial problems Moore believes the state union would be able to unearth. The nonprofit school network has a very healthy bond rating, Torkelson said, allowing it to borrow money at favorable rates. Only four other charter operators in the country are rated as strongly, the CEO said.

“To try to sabotage the financial operations of an organization, if not illegal, then is at least dirty tricks,” Torkelson said. “This is the sort of very sneaky political maneuvering that creates mistrust and that causes people to not want to be organized.”

Fenenbock says it’s not clear how much of the plan outlined in the email has been put into action. Moore proposed using public information laws to request district communications with CREEED; the number of records requests the district has fielded has more than doubled over the past five months, she says, requiring the hiring of an additional staff member.

“CREEED’s sole focus and intention is to improve education for children in El Paso,” she says. “I don’t know why someone would want to villainize that.

“We’ve always committed to trying new approaches,” Fenenbock concludes. “What we do know is if we keep doing what we’ve always done, we’ll keep getting what we’ve always gotten.”

On Nov. 9, the school board appointed Mickey Loweree, president of a district middle school PTA, to fill Fenenbock’s seat. The appointment is not expected to change the balance of power in the district.

For his part, Cabrera has said he hopes to have a district/charter partnership in place by the 2019–20 school year, AFT opposition notwithstanding.

“I’m greatly disappointed this email doesn’t talk about any partnerships going forward,” he says. “Instead, it talks about destabilizing the work we’re trying to do.”

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)