IDEA Public Schools Proving the Impossible Is Possible in Guiding Texas Alumni Through College Graduation

This is one chapter in an ongoing multimedia series by Richard Whitmire called The Alumni, which focuses on the efforts being made by America’s top charter networks in guiding alumni to — and through — college. Read all our school profiles here, and be sure to visit The Alumni microsite to see other essays, videos, graphics, and profiles of the educators and students leading a college success revolution: TheAlumni.The74Million.org.

While that rate may be four times the national average for students from low-income families and rising (48 percent of the class of 2008 earned degrees), it is below some of the East Coast charter networks.

But reaching the conclusion that IDEA experiences only middling success would be a mistake.

In truth, what’s happening at IDEA may be the most successful and revolutionary charter school experiment in the country. This month, the network is launching IDEA-U, a way to give those who “stopped out” of college (the polite term of art for dropping out) a path to complete a degree. And that’s just the latest example.

Understanding all this requires understanding the environment in which IDEA operates, which calls for visiting the Rio Grande Valley, surely one of the most unique regions of the U.S.

Stepping off a plane in McAllen, Texas, everything appears familiar enough, with the usual assortment of chain restaurants and hotels that pop up in small cities. But what visitors don’t see at first is how they are in a kind of no-man’s-land along the Rio Grande, where there’s a tidal movement of people moving across the border — in both directions.

Immigration officials don’t even attempt identity checks until Falfurrias, which is 75 miles to the north. And IDEA is smack dab in the middle of all of this. Its Riverview campus is called that because it overlooks the Rio Grande. Students who live in Mexico cross the bridges twice daily to attend IDEA schools, and no one bats an eye.

Whether those students were all born in the U.S., however, is hard to answer precisely.

Unlike charter networks in New York, Boston, and Los Angeles, IDEA — being in remote McAllen — has a far harder time recruiting teachers by tapping into the network of fresh graduates from the nation’s top universities — a cornerstone for staffing charters in those cities. So instead of trying to compete in a field where IDEA is at a disadvantage, the network is turning to those whom it knows — and who know it — best: IDEA graduates.

At IDEA’s Donna school, a sixth of the staff are alumni, some of whom are not only alumni, but are also Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals beneficiaries.

Even the university options for IDEA students in the valley are radically different. There are no nearby elites like Columbia University, Georgetown University, or the University of California, Los Angeles, to send their graduates. And the small, liberal arts colleges in Ohio, Pennsylvania, and New York that successfully absorb many graduates from East Coast charter networks — colleges with graduation rates in the 90 percent range — are also very far away.

While IDEA students apply to and win acceptance at high rates to many of the nation’s most selective colleges, only about 18 percent end up on that path. Instead, a full half of each graduating class ends up at the local University of Texas Rio Grande Valley, where the graduation rate is a modest 40 percent, far below what students would experience at selective out-of-state colleges.

And there’s only one reason that happens: money. Any scholarship offer short of a completely full ride, including travel expenses, is both daunting and mostly unthinkable.

At UTRGV, the price is right, the students can live at home and hold down a job, and they can please their close-knit families by not leaving the Valley.

Given all that, IDEA’s college success rate of 35 percent seems far above middling.

Nowhere is the push to hire IDEA alumni more apparent than at IDEA Donna, where alumni make up a sixth of the staff.

One April afternoon in the pre-AP U.S. History class Ramiro Flores teaches, everyone is reviewing for an upcoming state test. On the wall next to Flores’s desk are three diplomas: The University of Texas Pan American (now University of Texas Rio Grande Valley), an International Baccalaureate diploma earned at IDEA, and an IDEA diploma.

That’s a reminder to every 13-year-old in the class: I know what it’s like to be you, to grow up in families like yours, and to attend high school at IDEA.

But there’s more that makes Flores relatable to many of the students. He was brought to this country from Mexico as a child and now works in the U.S. under DACA.

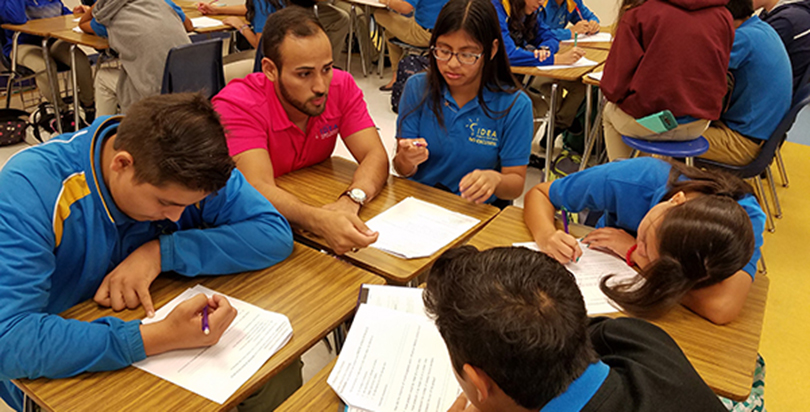

The students work in small groups, with Flores moving from group to group to assist, occasionally switching to Spanish. The students know all about the diplomas on the wall and Flores’s DACA status.

“Mr. Flores says history is mostly told from the white person’s perspective,” Emily Garza said, referring to a recent lesson on the Mexican-American War. “He likes to add the Hispanic perspective.”

Flores was born in Mexico and raised in Miguel Alemán, a tiny town of about 100 residents 160 miles northwest of McAllen, on the other side of the Rio Grande. But his parents didn’t think much of the Mexican schools. Plus, they wanted him to learn English. So every day, he commuted across the border to attend a private school stateside.

Flores and most of his family moved to the U.S. when he was in the ninth grade, and in 2007, he enrolled in IDEA Donna, hoping to receive a more rigorous education.

Flores never thought much about his legal status, and like all IDEA students he was told constantly he would enroll in a four-year college. During his senior year, Flores won a full scholarship to Wabash College in Crawfordsville, Ind. A week before he was supposed to leave to start his freshman year there, he heard from a college representative that scholarships were not available to students like him.

“I was kind of defeated. I had bought into this system of meritocracy,” Flores said. “Charter schools preach that if you are smart and hard-working you can go away to college and come back to serve. It was really a huge moment of depression in my life.”

Flores enrolled in then-UT-Pan American, and after a year attempted to transfer to American University in Washington, D.C., only to run into the same dilemma. So he continued at Pan American, where he earned two bachelor’s degrees in political science and economics in three years, and with a 4.0 GPA.

After graduation, Flores joined Teach for America as a corps member and went to Houston for training. He then ended up back at his alma mater, IDEA Donna.

Being an IDEA alum makes a difference to the students’ parents, as well.

“I had parents last year who were doubting whether their daughter could succeed in the IB program, so I sat them here and had them look back at my diplomas,” Flores said. “I let them know that when I was in eighth grade I couldn’t speak English, so in fact, their daughter was far ahead from where I started.”

Employing alumni brings authenticity to the IDEA program, Flores said.

“More than that, it shows that it is possible to succeed. I’m not going to solve the immigration issue today, or tomorrow, or at any point. But I’m at least able to have a very candid conversation about it with students who need to talk about it.”

IDEA college counselor Abby De Ochoa was born in the U.S. and grew up in Donna. Her parents came to the U.S. from Monterrey, Mexico, 150 miles southwest of McAllen. Her father is a carpenter; her mother is a business clerk. While her parents lack formal educations, they were insistent that De Ochoa’s educational experience would be different, which led to enrolling her in an IDEA charter in the sixth grade.

At first, the go-to-college emphasis at IDEA worried her parents, especially the push to look at colleges beyond the valley.

“In our background, it is not common for children to leave the house before marriage, especially as a young woman living by myself more than two hours away from home,” De Ochoa said.

But De Ochoa, who did well in both academics and sports, insisted on leaving the valley for college. She ended up at Kalamazoo College in Kalamazoo, Mich., with an aspiration to study engineering.

“I wanted to experience independence,” she said. “I also wanted to live through four seasons. Here in the valley, we don’t have four seasons.”

De Ochoa was recruited to play softball at Kalamazoo, which allowed her to attend all-expenses-paid. As part of her senior project for college, she did an internship with IDEA’s development team — a relationship that persisted and resulted in a job offer after graduation. When she decided she wanted more contact with students, she shifted to a college counselor position.

The big challenges she faces are familiar. IDEA parents want their children to stay in the valley, both to be close to the family and to work and contribute to the family income. That cuts into college success rates. And even small discrepancies between what a college offers and what IDEA families can pay leads to huge problems.

“We have kids who have gotten into Ivy League schools, with a great financial package, but are missing a couple of thousand dollars,” De Ochoa said. “Parents do not want that debt. They said, ‘My kid is not taking a $4,000 loan to go out of state.’”

That attitude is shifting, but slowly.

“The first batch of [IDEA graduates are] coming back, so the parents are getting used to the idea of [their younger siblings] going away for college,” she said.

The next difficult conversation with the families is graduate school.

“At first parents were happy with a high school degree. Then it was a college degree. But now it’s like an undergraduate degree is not enough. Soon, they are going to need master’s degrees,” De Ochoa said. “So it’s having that conversation with the parents that is most difficult.”

And yet, despite those disadvantages, IDEA is probably the fastest-growing charter network in the country, with plans to expand from its current 30,000 students to 100,000 students by 2022. Its leaders think they’ve figured out something special, and therefore have an obligation to expand to meet parent demand.

Tripling in size over the next six years should not affect the college graduation rate, said Phillip Garza, IDEA’s chief college and diversity officer.

“One thing that’s made us very successful is we have gotten really finite in terms of what an IDEA school is. We’ve just been building the same school over and over and over again. Each grade level has about 115 students. Every principal manages a school body of about 800 students. We’re very clear on what the pre-K-through-fifth-grade school is, and the sixth-to-12th school,” he said. “We’re very clear on how you ramp up, how you staff up, the budget model, the curriculum, the approach to non-cognitive learning. We just hire a leader that can essentially execute. So this is not a place where, for example, a fourth-grade teacher can say, ‘I’m not sure what a fourth-grader needs to know.’ No. We know what a fourth-grader needs to know, and we know how to get them to do that.”

Again, it’s all part of the belief that IDEA is onto something really big, and needs to expand to meet the demand.

“We are proving the impossible is possible in South Texas,” IDEA co-founder JoAnn Gama said during the network’s college signing day.

IDEA’s college signing day, held in multiple galas at a local arena to accommodate the growing number of IDEA graduates, is a cross between a sports rally and academic awards ceremony. Every IDEA student attends. Elementary school students in the nosebleed seats soak it up: “One day,” they are likely thinking, “that will be me on that stage, shouting out to a rocking, packed arena where I will go college.”

A few weeks later, Gama appeared at the annual New Schools Venture Fund gathering in San Francisco, possibly the most important convening of school reformers in the country. There, she was on a panel with KIPP CEO Richard Barth and Kriste Dragon, co-founder of Citizens of the World Charter Schools. The panel was a debate on “bigger, better, different,” with Barth arguing for better, Dragon for different, and Gama for bigger.

The instant feedback from the audience before the debate overwhelmingly favored Barth’s view. But as the session came to a close, when the audience voted again, it was Gama’s position that moved more of those in attendance.

“You can get better as you get bigger,” Gama said, citing academic improvements at IDEA amid rapid growth.

And that revolutionary attitude extends to college. IDEA wants 100 percent of students enrolling in four-year colleges, and most of them emerging with diplomas six years later. But that’s not all.

The real revolution, Garza said, comes from “democratizing” college — making it something available to all students, including some of the poorest students in the nation who grew up in the Rio Grande Valley or in poor neighborhoods in other areas of Texas, many of whom grew up speaking Spanish at home.

For that reason, Garza is at peace with so many students choosing the local option, University of Texas Rio Grande Valley, even if that diminishes IDEA’s college graduation rate.

“We have to remember that if IDEA had not opened its doors, a lot of our students who are now committing to going to the local college would not have even applied, much less gotten in, much less committed to attending the local college,” Garza said. “[Traditional] public districts across the nation are not on a mission to democratize higher education. They do not have teams of college counselors who ensure that 100 percent of seniors get into college, to ensure that 100 percent of seniors apply for [federal student aid], to ensure that adults are having strong fit-and-match conversations with students.”

One way college gets democratized here is just unfolding: IDEA-U, a partnership with College for America, which is part of Southern New Hampshire University, a program that marries the needs of nontraditional students (the need to work, or raise a family) with the flexibility of online classes — but with a brick-and-mortar site where they can study uninterrupted and get mentored.

Not all students are born destined to get dropped off at leafy, pricey colleges and emerge four years later with a bachelor’s degree. This is for those students, a hybrid college. The first actual site for IDEA-U will be IDEA’s old headquarters.

“We’re onto something at IDEA, which is why we feel the imperative to grow,” Garza said.

And to IDEA, growing means ensuring college for all its alumni, even those who dropped out of college.

The first IDEA-U opens in August with 50 students, who will pay $5,500 a year for tuition and fees. For students who qualify for a full Pell Grant, they will pay nothing out of pocket. The center will be open during business hours, nights, and weekends.

Giving students an out-of-home place to study, away from laundry, children, and other distractions, is a big part of the strategy. At the center, students will meet regularly with advisers to keep them on track.

“While IDEA graduates complete college at rates three or four times the national average for low-income students,” said Garza, “there are still a number of students who struggle to persist due to unforeseen challenges.”

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)