Surviving Genocide: Native Boarding School Archives Reveal Defiance, Loss & Love

As archivists push to bring the history home to tribes, letters, newspaper clippings and photographs offer glimpses of brutal day-day student life

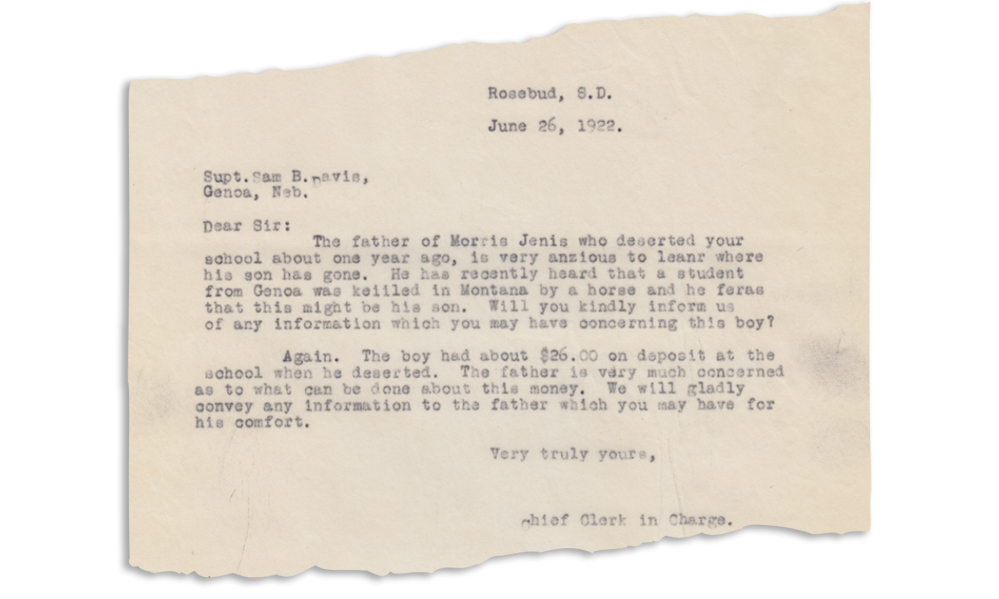

By Marianna McMurdock & Meghan Gallagher | October 4, 2022It is a desperate plea from a father seeking information about his missing son.

Morris Jenis Jr.’s father knew only his son, a Native American student at the Genoa Indian School in Nebraska 100 years ago, had not been seen in a year.

Morris ran away from the school in 1921 — “deserted,” according to the militaristic language school officials used — like hundreds of other young Indigenous children who resisted the boarding school policies that forcibly stripped them of language and identity, often hundreds of miles from home.

“The father…is very anxious to see where his son has gone,” a school clerk wrote the superintendent on the father’s behalf. “He recently heard that a student from Genoa was killed in Montana by a horse and he fears that this may be his son.”

Public archives do not provide any answers about Morris, nor his age and tribal affiliation. The school told his father that they could not find “any trace of him,” and reportedly returned the $26 — worth about $450 today — his family previously paid to send him home.

The plea is among thousands of stories made public by the Genoa Indian School Digital Reconciliation Project, one of many efforts to digitize elusive school, state and federal records, to bring the stories of Indigenous survivors and those who never made it home back to their families and tribes.

Last summer, the discovery of more than 900 child graves at former Canadian residential schools tore through international media and reignited investigations of U.S. boarding schools; reports focused on brutal abuse and quantifying death.

Archivists and community members have continued to retrieve haunting letters, student and local newspapers, photographs and other school documents that paint a poignant picture of resistance and survival in day-to-day student life in the boarding schools.

Still, many records remain out of reach to descendants, and those that are accessible can be traumatizing. Some collections sit dormant, held by churches or universities with no plans to return them to tribal communities; others require extensive time and travel to physical archives.

“Native people have never had easy access to their records. And that in itself has continued to contribute to the genocide,” said Tawa Ducheneaux. a citizen of the Cherokee nation working as an archivist at Oglala Lakota College’s Woksape Tipi library on the Pine Ridge Reservation in South Dakota, where she raised her family for 19 years. “You’re not having access to relatives and descendants that can educate you more about who you are and where you come from.”

Among the archived collections are receipts for music lessons, requests to use funds to buy shoes, picture contests — a glimpse into students’ interests and how they spent very limited leisure time. Others include letters from parents pleading that their child be allowed to travel home for the summer — a trip families were required to pay for.

Student discipline records and letters show many of such requests denied for lack of funds or because children had to continue building “strength of character,” as a punishment for bad behavior or running away.

Parents encouraged runaways, hid their children, and, when students were able to return home for summers, would teach children their language, culture, and ways of life as a way to undermine the schools’ assimilationist aim. Families would not legally be able to deny placement in off-reservation schools until 1978, after over a century of resistance, with the passage of the Indian Child Welfare Act.

For those working to find and make material more accessible, the retrieval and research is exhausting, but a necessary step toward healing and reckoning with historical trauma.

“It’s painful especially when you recognize relatives’ names or people that you know … I kind of learned to reconcile with that and just understand that, OK, well, maybe my involvement is that these children, they need help to have their stories come to light,” said Genoa Project co-director and historian Susana Geliga, a member of the Rosebud Sioux tribe and of Taino descent.

“They insisted on their humanity:” Student life as seen in archives

The material that has been made available in digital archives is largely from an official government or school perspective. Yet there are phrases, quotes and clippings from students pointing to how they lived and survived.

Running away became a common occurrence among students fleeing the conditions of the boarding schools, eager to find a way home, like Susie Romero. Before leaving for Genoa one night in 1933, Romero composed a theme song — “I don’t want to go to school here.” In just one year at the Carlisle Indian Industrial School in Pennsylvania, at least 45 boys did the same.

“…That tells you a lot about the children’s point of view — that they were running away from this,” said Margaret Jacobs, co-director of the Genoa Project and historian at the University of Nebraska – Lincoln.

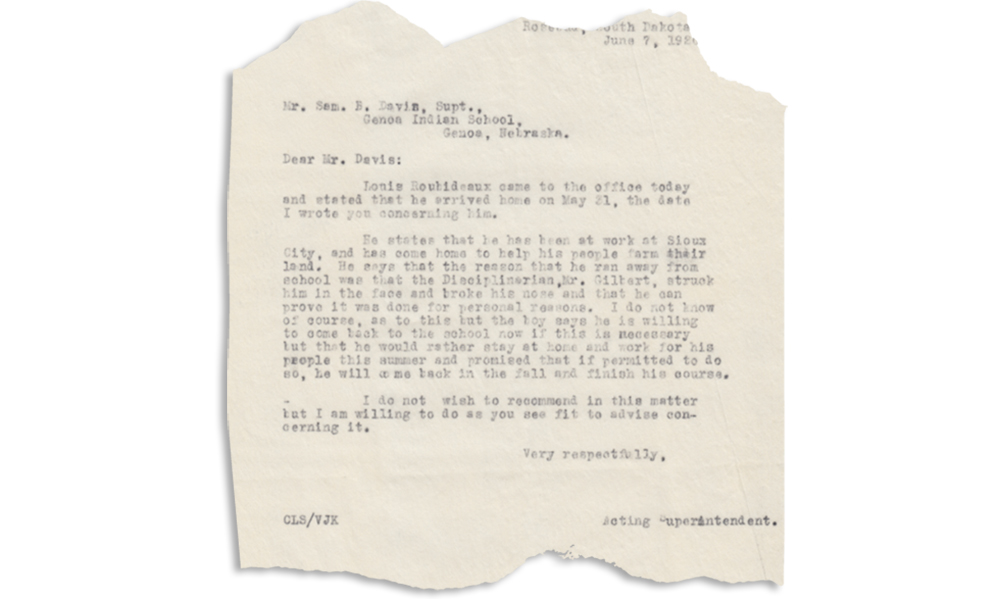

The documents suggest Romero was discovered and returned to Genoa, but some did find their way back home. In 1920, one student left Genoa for good after a teacher struck him in the face, breaking his nose.

“He can prove it was done for personal reasons,” an acting superintendent wrote in a letter seeking guidance.

Student newspapers, common at the boarding schools, though likely heavily scrutinized by school officials, also reveal how students kept themselves informed of local and national news and found ways to make art.

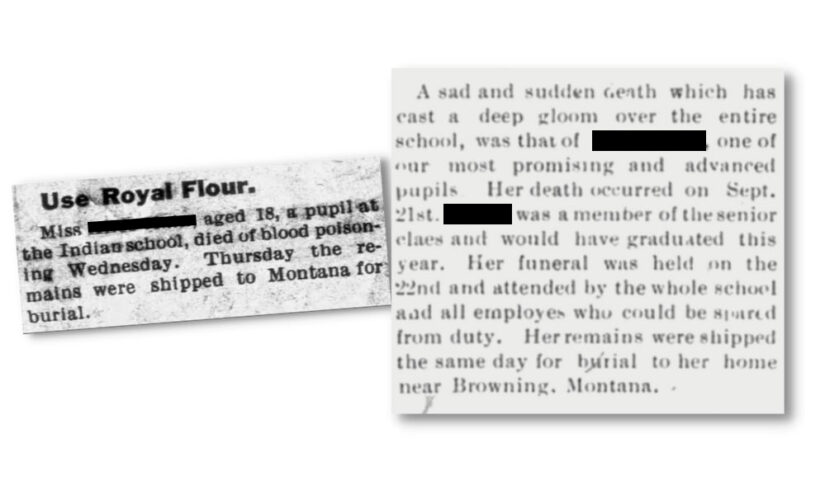

When compared to how student deaths were reported briefly in the local Genoa paper, student publications shared more detail on their peer’s life and personality. One student, whose name has been redacted out of respect for descendants who may not yet know the information, was described as an “unusually bright child and the little ones among whom his lot was cast will miss his fair example.”

Jacobs said the student newspapers, “insisted on their humanity. They insisted that we matter, and you might not care about us, but we care about each other.”

Some 90 students, in one account published in the Genoa student newspaper, were reportedly in attendance for a funeral at the school — a detail not lost on Geliga.

“They were so policed and monitored with everything that they did … from the time they woke up until the time they went to bed every day …” she said. “Those instances where you can catch their own perspective coming through, they’re really heartwarming because there’s so few and far between — when you find them they kind of pull you into the moment.”

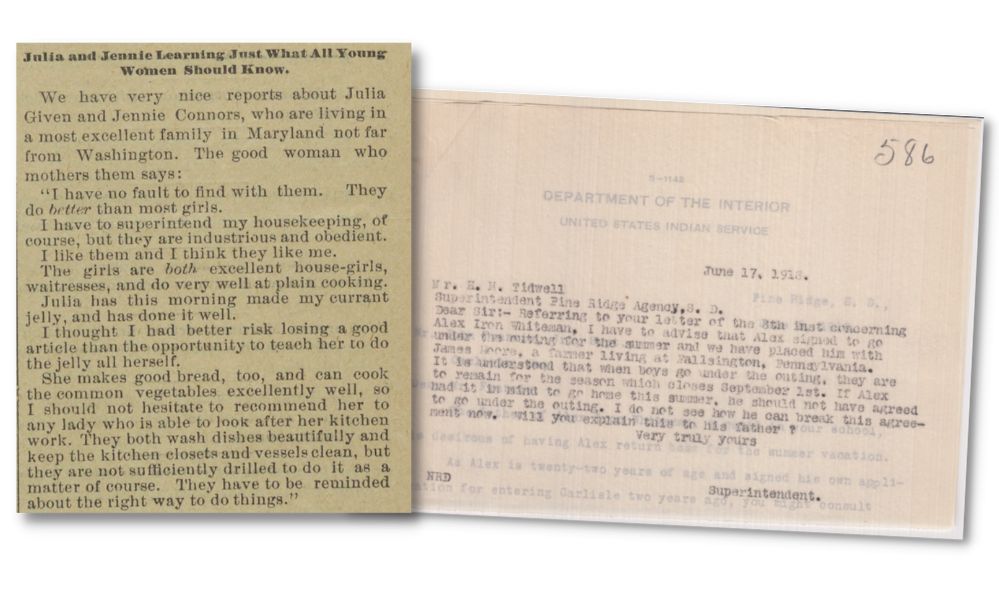

Archives also reveal another facet of student life: the “Outing” system, where children were assigned to white families and expected to work in fields, on ranches and in local homes as part of their “civilizing” process. Piloted at Carlisle, the practice was later adopted by other off-reservation schools including Genoa and the Sherman Indian School in Riverside, California.

Lorenzia Nicholas, a student at Sherman, once refused to return to the family she was placed for outing because of “poor treatment.”

Though they were paid minimally, students were often forced to go on outings during summer vacations instead of returning home to their respective lands and families. The practice grew popular in communities surrounding the schools: children were a source of cheap labor — girls often cleaned homes and looked after white children, while boys were often placed in undesirable harvest jobs that were rarely supervised, exploitative and dangerous.

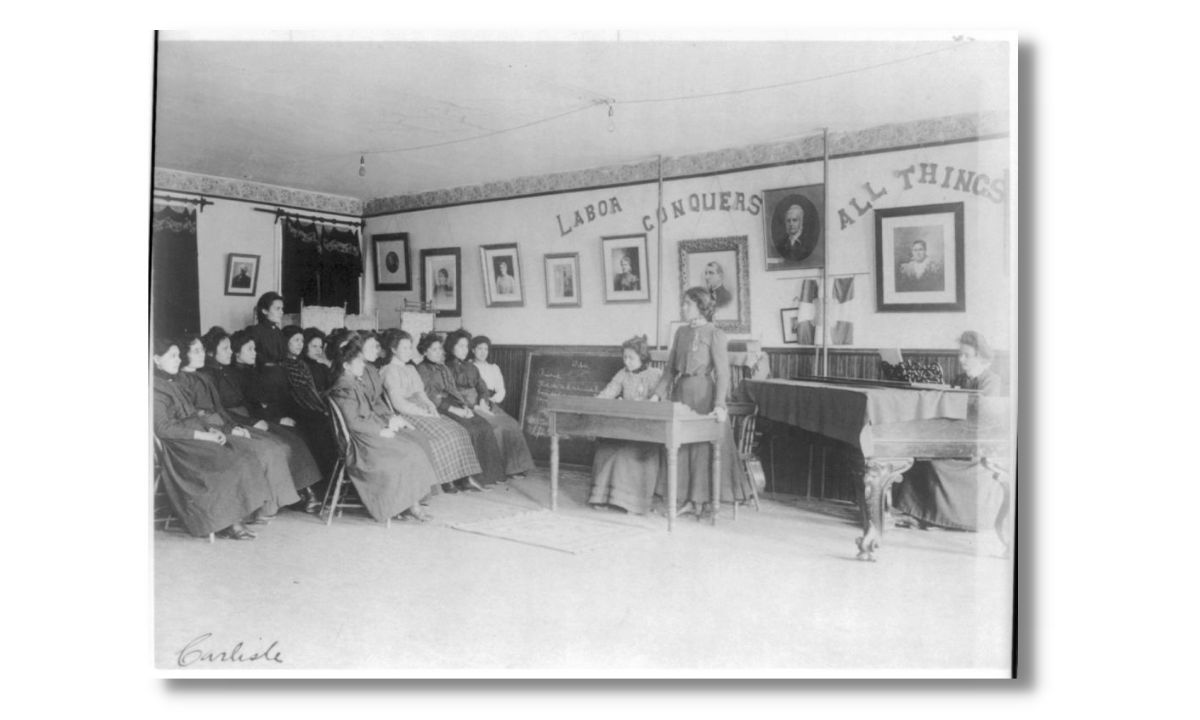

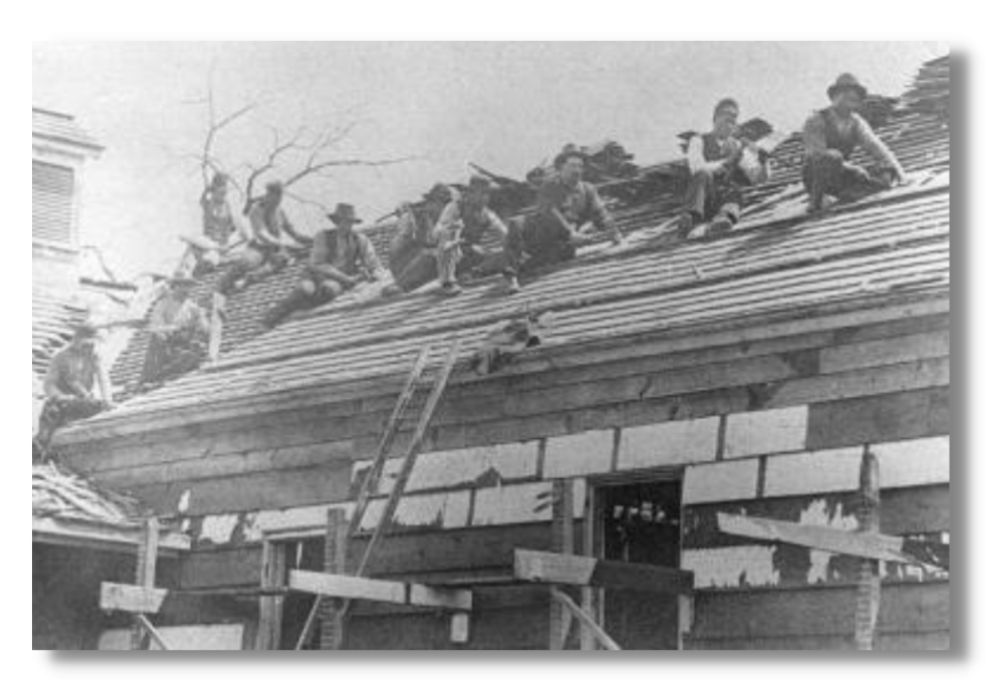

On campus, labor did not stop. Children as young as 9 were forced to do manual work, likely, Carlisle archivist Jim Gerencser told The 74, to save on infrastructure costs. Half of their school days were devoted to learning vocational trades; photographs show students fixing roofs, washing clothes in “laundry class” and fashioning utensils.

Expanding access to archival records, family history

In Canada and the United States, churches are holding onto an untold number of records. Many religious institutions received federal support and funding to operate schools until 1928, yet according to the Department of the Interior’s investigation, must independently decide to share documents.

Ducheneaux added tribal governments only recently have had the infrastructure or resources required to retrieve and disseminate records held in various public and government archives – tribal colleges and universities have been working at returning access since at least the ’60s.

Some records have been passed on to private universities like Augustana and Marquette instead of tribal communities and descendants, presenting another barrier to access: fees. Marquette has held a collection including at least 10,000 images from the Red Cloud Indian School for nearly 14 years, only having digitized about 10%.

“[It] is maybe the only collection that might have images of certain individuals’ relatives … There’s no known images of that person except possibly within that collection,” she said. “And I couldn’t ever get anywhere with them. We have to do justice to all these people that are contacting us asking if we have anything about their relatives.”

An intergenerational legacy: “It’s part of the blood that’s in us”

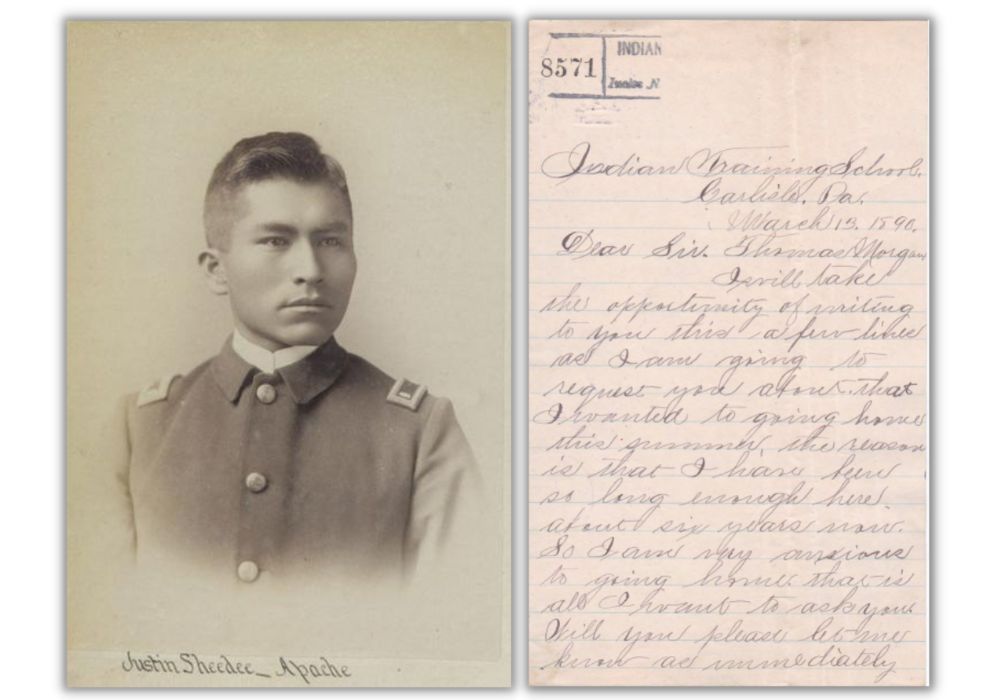

Justin Shedee, a member of the Apache nation also known as Corn Cobb Smoker, entered the Carlisle Industrial School in Pennsylvania at 16. Though a letter in his own handwriting expresses his desire to leave, school documents say he “consented” to stay enrolled.

“The reason is I have been so long enough here, about six years now. So I am very anxious to [go] home. That is all I want to ask you,” he wrote in the spring of 1890, requesting to leave the school.

He would not leave for three more years, “discharged” on July 5, 1893 for “ill health.”

Shedee’s desire to return home lives on in descendants. Community members, scholars and activists describe the weight of their ancestors’ experiences as intergenerational trauma that impacts their current health and ways of life.

Native American communities and over 80 U.S. representatives are advocating for legislation that would establish a Truth and Healing Commission on Indian Boarding School Policies to create a commission to investigate nearly two centuries of boarding school policies.

Among the policy recommendations that have been floated are reparations, a hotline for those experiencing intergenerational trauma, and reformed child welfare adoption practices to prevent “modern-day assimilation.”

“We’ve been subjected and our ancestors have been subjected to such atrocities and such attempts to wipe us out that we’ve sort of normalized suffering, in a way,” said Stacy Bohlen, CEO of the National Indian Health board and member of the Sault Ste. Marie Tribe of Chippewa Indians, during a webinar hosted by the National Native American Boarding School Healing Coalition.

“It’s part of the blood that’s in us and the blood of our ancestors that we know was shed for our survival.”

This story was made possible by the archives and archivists at the Genoa Indian School Digital Reconciliation Project, Carlisle Indian School Digital Resource Center, and National Archives.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter