Federal Probe into Native Boarding School Deaths Likely a Severe Undercount

By Asher Lehrer-Small & Marianna McMurdock | May 13, 2022

Less than 5% of known facilities account for over 500 child deaths, the Department of Interior’s report revealed

Born and raised on Navajo and Ojibwe reservations, three of endawnis Spears’s four grandparents were among the estimated hundreds of thousands of Native children separated from their families, their tribes and their traditions and forced to attend government-run Indian boarding schools.

A federal Bureau of Indian Affairs officer took Spears’s maternal grandmother at just 6 years old from Arizona to the Albuquerque Indian School in New Mexico. The agency threatened the young girl’s parents with possible jail time if they did not surrender her.

Her paternal grandmother was sent across state lines from Minnesota to Kansas, where she was forced to attend Lawrence’s infamous Haskell Indian Training School, unable to return home for nearly a decade.

After hiding from federal officers for years, agents took her maternal grandfather at 14 to Fort Wingate, Arizona and forced him to cut his hair, pray to a Christian god and speak English, though Navajo was the only language he knew at the time. The teen repeatedly tried to run away, and staff punished him by forcing him to spend days on end in the school’s basement without food. Spears’s parents shared these stories with her over the years.

“These legacies and these histories are so intimate to us as Native people,” said Spears, who now lives in Hopkinton, Rhode Island and serves as Brown University’s Tribal Community Member in Residence. “We carry them in our DNA.”

At least 500 Indigenous children died while attending federally operated Indian boarding schools, according to a May 11 report from the Department of the Interior. Just 19 facilities, a small fraction of the 408 government-supported schools identified, account for that tally — meaning the death total is likely a severe undercount.

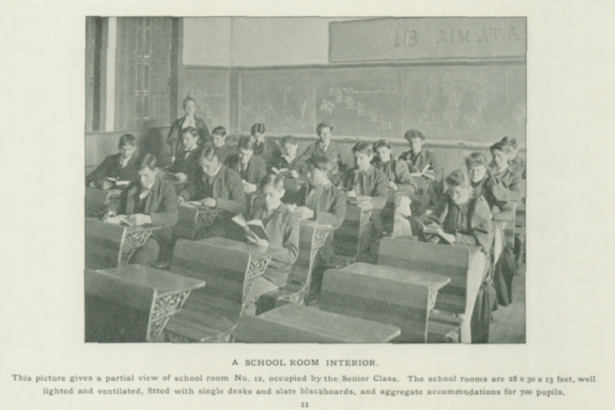

For 150 years, up until the late 1960s, the U.S. government stole Indigenous youth from their communities, often without parents’ consent, and sent them to Indian boarding schools where they were forced to use English names, wear Americanized haircuts and perform military drills. Many children suffered physical and sexual abuse, and an unknown number died, often from overcrowding and unsafe living conditions.

The long-awaited report represents the first time the federal government has attempted a systematic accounting of the facts and consequences of the Indian boarding school system it perpetuated.

“I’m glad to see it on the news. I’m glad that there are people asking these questions because our Native families, our Indigenous families in this country carry these stories with them every day,” Spears told The 74. But the process is only beginning, she added.

“We’re just learning the full scope of the truth. … People always want to jump to reconciliation and they want to skip over the truth-telling part. We need to sit in the truth for a while.”

The May report represents Volume I of an investigation that Interior Department Secretary Deb Haaland, a member of the Laguna Pueblo tribe and the agency’s first Indigenous head, unveiled in June 2021. The effort is intended to provide a basis through which the U.S. may reckon with past brutality by locating gravesites — many of them unmarked or erroneously named — repatriating children’s remains and offering resources to affected families.

“It is my priority to not only give voice to the survivors and descendants of federal Indian boarding school policies, but also to address the lasting legacies of these policies so Indigenous peoples can continue to grow and heal,” said the secretary, who’s own grandparents were also subjected to the boarding school system.

Indigenous scholars underscore that this first report only conveys a small fraction of the violence wrought by these schools, scores of which were operated by the Catholic Church and various Protestant groups at the government’s behest.

“Basically every school had a cemetery,” said Preston McBride, an Indian boarding school historian and a Comanche descendent. “There are deaths at or deaths because of virtually every single boarding school.”

“The United States doesn’t even know how many Indian students went through these institutions, let alone how many actually died in them,” he added.

In his own research, he has documented over 1,000 child deaths at just four boarding schools. He estimates the toll over the entire system’s century and a half of operation may be as high as 40,000.

The Department of Interior declined to comment on whether it believes that to be a plausible estimate, though the report’s authors note they expect “continued investigation will reveal the approximate number of Indian children who died at Federal Indian boarding schools to be in the thousands or tens of thousands.”

“Each one of those individuals is a story, had a story, has a story. And each one of those individuals did not have the opportunity to continue their traditions, to continue their culture, their language, to have a family — to be able to pass down the knowledge, the practices, the language that they inherited from generations past,” Samuel Torres, deputy CEO of the National Native American Boarding School Healing Coalition, told the 74 after the investigation was first launched.

Spears said her grandparents did not talk about witnessing deaths at the boarding schools, perhaps to protect their family from that horror.

Amazingly, her grandfather, George Kirk, who suffered deprivation and torture at the hands of the U.S. government, later went on to help the country win World War II. Kirk became a famed Navajo Code Talker, one of 29 U.S. Marines whose skill at transmitting over 800 messages without error in a coded version of their native tongue proved a critical advantage to Allied forces.

“The very language he was starved for speaking, later helped save this country,” Spears said.

To bring the boarding school history to light, the Interior Department’s research team is working through the review and electronic screening of roughly 500 million pages of documents held in the American Indian Records Repository in Lenexa, Kansas.

Most of the staff who have worked on the report are themselves Indigenous, NBC reported.

“It’s been an exhausting and emotional effort for them to confront this horror on a daily basis to bring this information to you,” said Assistant Secretary Bryan Newland, who led the investigation and is a member of the Ojibwe nation. “This has left lasting scars for all Indigenous people. There’s not a single American Indian, Alaskan Native or Native Hawaiian in this country whose life hasn’t been affected by these schools.”

As the team continues its investigation, they hope to further clarify the U.S. government’s role in supporting the Indian boarding system, determine the location of more burial grounds associated with these schools and identify the names, ages and tribal affiliations of those buried there. They have already identified over 50 marked and unmarked gravesites.

The Interior’s investigation, the beginnings of what may become a public, centralized archive, will continue with $7 million in additional Congressional funding through fiscal year 2022.

The report follows a similarly disturbing reckoning in Canada and builds on years of Native-led activism to unearth the truth behind U.S. boarding school policies. Since its founding in 2012, the Boarding School Healing Coalition has filed for the investigation of missing children before the UN, conducted their own research, supported survivors, and led repatriation efforts for 22 children who were buried at the Carlisle Industrial School in Eastern Pennsylvania.

“I don’t think the impact [of the Investigation] can be underestimated. This is such a big part of American history that has not been talked about,” Jim Gerencser, a Dickinson College archivist who co-founded a massive public online database cataloging Carlisle’s history, told The 74 last year. Many people have reached out to him looking for in-depth archives of boarding schools, family information or sources to incorporate in their K-12 classrooms.

Carlisle has become one of the most studied U.S. boarding school sites, in part due to its size and founder’s infamous propaganda to “kill the Indian and save the man.” The site forcibly enrolled over 10,000 children from 142 Native nations over the course of 40 years.

Spears and her husband Cassius Spears Jr. — first councilman for the Narragansett tribe and nephew of former councilwoman, Tomaquag Museum leader and educator Lorén Spears — have worked to reclaim many of their Native ways of life for their children. Her boys grow their hair out long and have pierced ears. They teach their kids about humans’ relationships with plants and non-human animals. They learn words and prayers in Native languages.

“I make decisions everyday to give my children what my grandparents couldn’t have,” said Spears.

Lede Image: Dan Romero or Walking Bird of the Ute Tribe encircles the graves of children with sage at Sherman Indian School Cemetery in Southern California. (Cindy Yamanaka/The Riverside Press-Enterprise via Getty Images)

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter