A ‘New Normal’: National Student Survey Finds Mental Health Top Learning Obstacle

LGBTQ youth report suicidal ideation 30% more often than peers; students of color access school counselors, therapists 7-10% less than white peers

Get stories like this delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

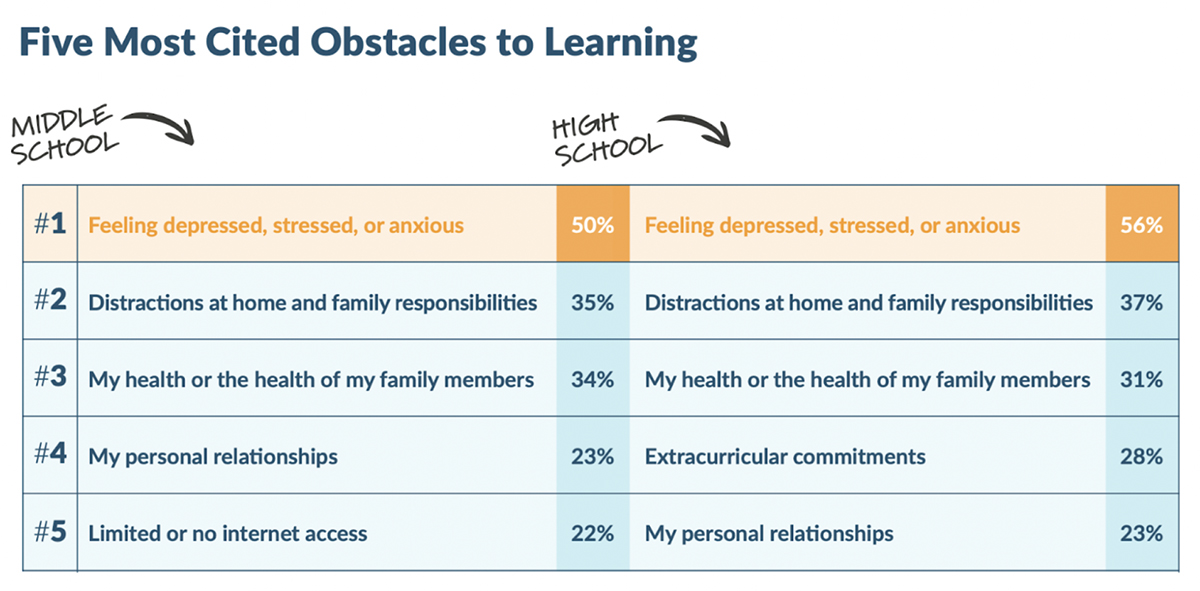

Depression and anxiety continue to plague an overwhelming number of America’s middle and high school students, particularly LGBTQ and students of color, hampering efforts to boost learning from pandemic losses.

Secondary students at every grade level maintain depression, stress, and anxiety is the most common barrier to learning. And fewer than half of them, regardless of gender, sexual and racial identity, have an adult they feel comfortable talking to when stressed or upset, according to a new report from YouthTruth.

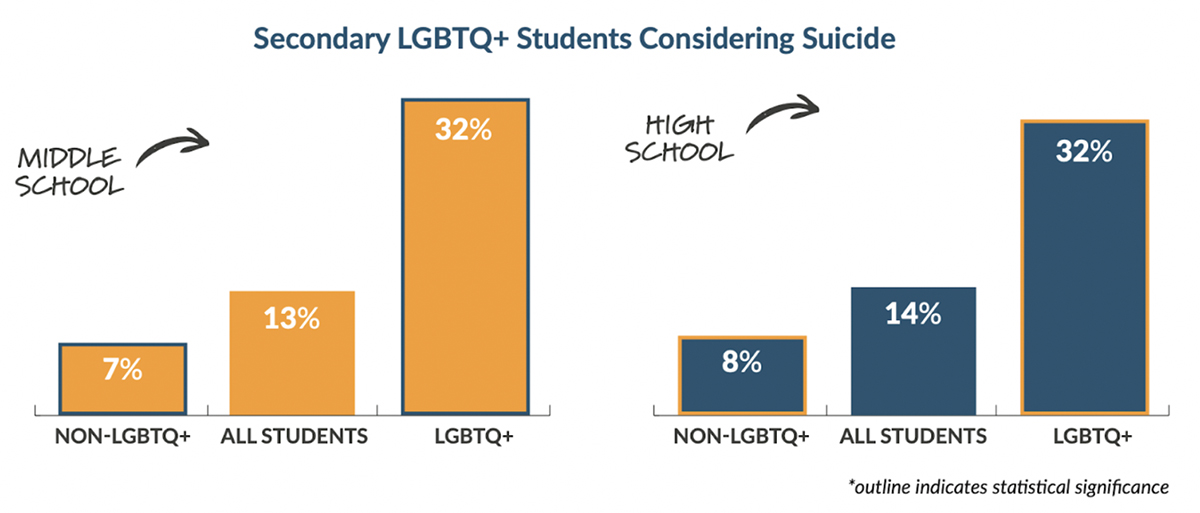

The report also reveals drastic mental health disparities, with white students students at least 7% more likely to access a school psychologist, counselor or therapist than their Black, Latino and Asian peers. LGBTQ youth experienced suicidal ideation more than double the rate of their peers.

“The increase in the mental health load that students experienced during the pandemic has not gone away, is still very present, even increased and it’s not going away anytime soon,” said Jen Wilka, executive director of YouthTruth. “For now, we need to adjust to that as the new normal and and think about how we support students.”

The survey found that last academic year, less than a quarter of students spoke to school counselors, therapists or psychologists about what they were facing.

“I think that the conversation about learning loss and the academic side of learning is so loud, that we can sometimes lose sight … of the interconnectedness between emotional and mental health and students’ ability to learn academically,” Wilka added. “It’s really impossible to do one without the other.”

Less than half of the 222,837 students surveyed this fall across 20 states are satisfied with their school’s mental health offerings. “I wish the school did more to train and educate its students on how to identify … warning signs of deteriorating mental health, abuse, self-harm, and violence within their peers – and respond appropriately and compassionately,” one Asian-American high school senior boy wrote.

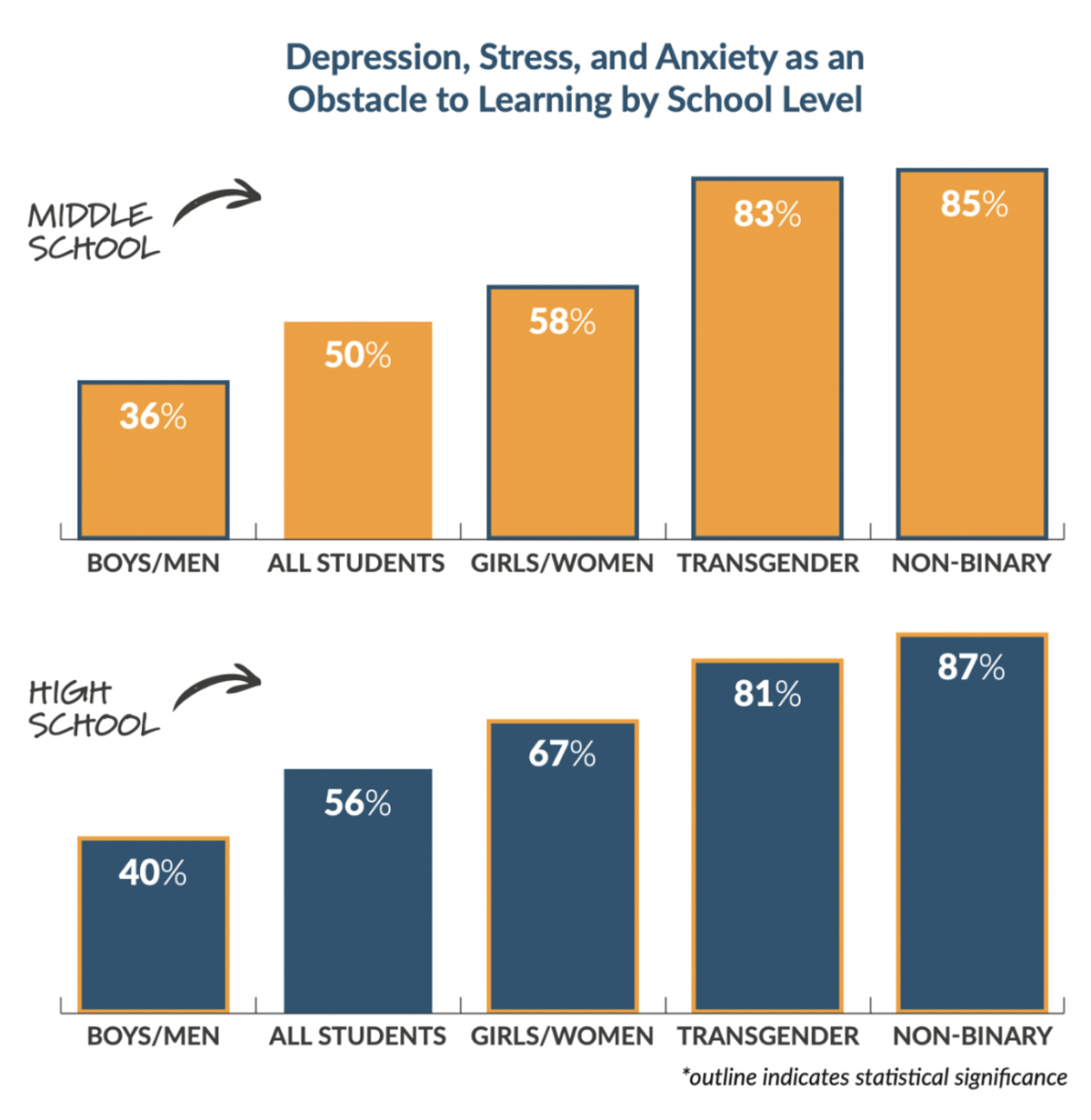

Gender disparities

YouthTruth’s findings, disaggregated for the first time by gender identity, also reveal starkly different emotional realities and gaps in access to meaningful care for LGBTQ students.

An overwhelming majority, 83-85%, of trans and non-binary students say depression, stress and anxiety block their ability to learn, rates at least 33% above the average for all students. LGBTQ middle and high school students report twice as much as their peers that bullying also impacts their learning.

Only about a third of LGBTQ students report their school’s mental health support is satisfactory.

“That says that we still have work to do to meet those students where they’re at and be tailoring that support,” Wilka said.

LGBTQ students want to feel “seen and recognized” in curriculum, which would contribute to a positive sense of self. Recent efforts to censor content at school have plagued students’ mental health, write-in responses reveal.

Curriculum bans launch a domino effect, stifling classroom talks about gender and sexuality. The culture makes it difficult for students to process traumatic events when they may not freely be able to at home, and to feel a sense of belonging.

Distinctive Schools, a charter network in Chicago and Detroit and YouthTruth partner, is currently ramping up support for LGBTQ students — encouraging active Gay-Straight Alliances on each campus and making their dress code language more gender inclusive — and expanding their mental healthcare teams to combat mental health stigma.

“I’m giving trainings to teachers that historically you would only get as a clinician…and we can still be doing better, they still need more, and we still can’t keep up with the demand,” Distinctive School’s Director of Clinical Services, Michele Lansing, told the 74. Their suicide or risk assessments are up, the result of peers sharing their concern for one another more frequently.

“Our students are more educated and getting better at putting words to what was already there, ”Lansing said.

“They know that their friends deserve help and support.”

Boys were the least likely subgroup to speak with school staff about their mental health or the problems they experience, at about 15%. One young student, in a workshop analyzing his school’s results, hypothesized that a “culture of masculinity” impacts the numbers — there’s an expectation that boys shouldn’t express their feelings.

“Even though in this data, we might look at it and say ‘oh, boys and young men are doing fine, it’s girls, transgender, and non-binary students that we need to be worrying about.’ We know from other data that boys and young men are not fine,” Wilka said.

“Do better:” Involve students, families

The overwhelming ask from students’ write-in responses is now “do better.” The plea is a stark shift from past surveys, where students wanted schools to do something, anything, to address the mental suffering they experience and witness.

“That refrain, ‘talk to us first’ is just exploding in the qualitative data right now,” Wilka said, adding that the message suggests schools can do more to bring students into the process of planning or adjusting offerings. Distinctive Schools, for example, meets each family individually at the start of the year.

“We’re young, but we deserve respect,” one white high school senior wrote in their survey response, criticizing what they felt were inadequate attempts to address needs by adding mental health days.

“Don’t just hear us, listen to us,” another wrote, “ …You have to work alongside us, or it just doesn’t work. Do something … Do better.”

The new normal is not at all surprising to Makayla, a Black high school junior at one of Distinctive School’s Chicago high schools. She asked her last name not be used to maintain privacy.

“I have experienced all three — the depression, stress and anxiety, and it definitely did affect my work … I was torn apart, and so many days, I just wasn’t okay,” she told The 74.

Typically a high-achieving student, Makayla found it harder and harder to stay emotionally stable last spring, often sitting in the counselor’s office collecting herself for most of the school day. Her grades plummeted. Yet she was among the minority of secondary school students comfortable enough with her teachers to be honest when they took notice.

“On the days that I would come to school while I was mentally not okay, my English teacher, she was like, ‘do you need to take a breather? Do you want to just sit here and catch up on work later?’ ” Makayla said. “…They understand that if you need a moment, then I’ll give you a moment, or however long it takes.”

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)