Study: Damage from NAEP Math Losses Could Total Nearly $1 Trillion

Researchers found that gains in eighth-grade math are closely correlated with outcomes like high school graduation, college enrollment, and earnings

Get stories like this delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

Federal test scores released last week illustrated the extent of COVID’s impact on K-12 learning, revealing the largest-ever math declines in the history of the National Assessment of Educational Progress. In virtually every state and major school district, fourth and eighth graders demonstrated far less mastery over the subject than students who took the test before the pandemic.

But that academic slippage isn’t measured only in scale points and proficiency standards. In a new study timed to coincide with the NAEP release, researchers found that the erosion of math skills experienced by America’s eighth graders may lead to hundreds of billions of dollars in lost earnings over the coming decades. Other important life trends, including high school graduation, college enrollment, and criminal arrests, are also likely to be adversely affected by years of thwarted schooling.

The research offers a perspective on the immediate damage wrought by the pandemic, but also a penetrating observation about the relationship between students’ performance on standardized tests and their chances of future success. Douglas O. Staiger, an economics professor at Dartmouth and one of the paper’s co-authors, said that part of the motivation for the work was to explore whether progress on indicators like NAEP is connected to the authentic development of intellectual ability or simply the product of “teaching to the test.”

“We interpret this evidence as saying that NAEP means something,” Staiger said. “When there are improvements in scores, those kids coming out of school are going to have better outcomes later in life. And we can infer from this recent decline that all the cohorts in school now are going to do a bit worse than we expected.”

Experts have attempted to quantify the long-run costs of the pandemic since its early months. A model created in 2020 by economists for the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development concluded that each additional quarter of disrupted learning could result in tens of trillions of dollars in vanished economic activity.

The latest study used 2022 scores, available only for a matter of days, to project the potential consequences of COVID-era learning loss. But its analysis was principally based on decades of data from prior NAEP releases, which the research team used to generate a picture of how eighth-grade achievement in math correlates with students’ subsequent prospects in life.

Staiger and co-author Tom Kane, a Harvard economist and faculty director of the university’s Center for Education Policy Research, collected testing records for about 125,000 students attending nearly 4,800 schools over multiple decades. Test-takers sat for the eighth-grade math exam multiple times in the 1990s and biannually since 2003. (Before 2003, participation in NAEP was not mandatory, though at least 38 states administered the test each year.) The average scores were used as a metric for general math performance among students born in each state 13 years prior.

Next, they combined that information with representative responses from both the U.S. Census and the American Community Survey — which provided state- and year-specific data on income, educational attainment and teen motherhood — as well as FBI estimates of both violent and property crime arrests by age, year, and state.

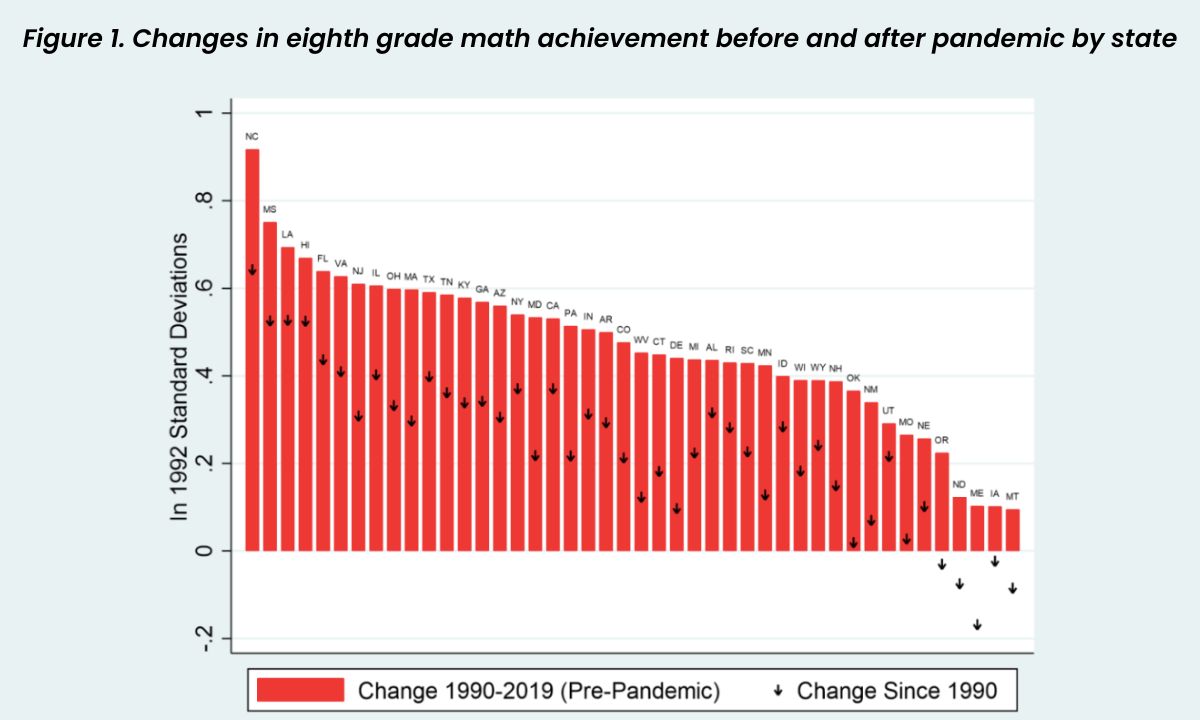

An assessment focusing solely on NAEP trends shows that eighth graders experienced substantial growth in math from 1990 to 2019, but that growth was highly variable across state lines. Students in North Carolina, where scores increased the most over that time, saw improvements roughly nine times the magnitude of those in comparative stragglers. And dishearteningly, the 2022 results show that achievement has shrunk in every state, including five (Oregon, North Dakota, Maine, Iowa, and Montana) in which eighth-grade math scores are now lower than they were 32 years ago.

Still, Staiger argued, even with the persistence of achievement gaps across race and socioeconomic status, the scale of progress in the last three decades has been “astounding.” While the pandemic has, at least for the moment, lowered the baseline for average math proficiency, some of the benefits of past growth are still with us, he added.

“We’re still way ahead of where we were in the 1990s, even though some states have slipped back,” said Staiger. “This doesn’t mean we shouldn’t be thinking about helping these cohorts, because we’ve now reset the norm. But we really should be celebrating the incredible things that schools and teachers have done over the last 30 years.”

But the apparent influence of those gains on later-life outcomes was even more striking. After controlling for the possible effects of race, gender and educational attainment of parents (all of which could exert a powerful sway on young lives independently of their classroom learning) Staiger and Kane found that growth in eighth-grade math was positively correlated with high school graduation, college enrollment, and life earnings from age 28. Girls born in states with relatively higher scoring jumps were also less likely to become teen mothers, while boys were less likely to be arrested for violent crimes or institutionalized.

Across the country, the average NAEP math achievement for eighth graders rose by 18 points between 1990 and 2007 (the year when today’s 28-year-olds were enrolled in eighth grade); that rise was associated with an annual boost to earnings of 4.2 percent. In best-in-the-nation North Carolina, the increase in earned income was even higher at 7 percent.

But that happy news must be revised in light of the pandemic-era learning loss illustrated by last week’s NAEP release. The average decline of eight points would conversely imply a loss of 1.6 percent of earnings. Using existing estimates of Americans’ lifetime income, the authors present a rough calculation of what that would mean across 48 million public school students: $900 billion.

That stark projection assumes that the learning effects observed over three school years — massive learning loss beginning in spring of 2020, then likely reaching its nadir in 2021 before rebounding more recently — are rendered permanent. Several pieces of contemporary evidence indicates that this will not be the case, as the recent release of state test scores show reading and math performance climbing gradually upward.

But some researchers argue that a complete turnaround will only come through historic changes to K-12 schooling in the years ahead. Harvard’s Kane has publicly struck a pessimistic tone, noting in a conversation with The 74 that the learning recovery strategies implemented in most states won’t come close to reversing the full impact of learning loss for all K-12 students.

Staiger issued a similar call to urgency, arguing that the $190 billion cost of the federal government’s pandemic aid to schools would be well spent if it could trigger a revival of math performance and earning potential. Hints of progress from the return to in-person learning could still end in the diminished learning trajectories of tens of millions of students, he added.

“They’re not saying that test scores are back to where they were. We’re half a year behind, and we’re staying half a year behind. So you ask, are we going to catch up by 2024? If we do nothing and just go back to business as usual, I don’t think there’s a lot of evidence that we will.”

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)