Students Headed to High School Are Academically a Year Behind, COVID Study Finds

As federal funds dry up, eighth graders feel the pandemic’s long shadow most acutely, according to NWEA researchers.

Get stories like this delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

Eighth graders remain a full school year behind pre-pandemic levels in math and reading, according to new test results that offer a bleak view on the reach of federal recovery efforts more than fours years after COVID hit.

Released Tuesday, the data from over 7.7 million students who took the widely used MAP Growth tests from NWEA doesn’t bode well for teens entering high school this fall. Finishing 4th grade when the pandemic hit, many students not only lost at least a year of in-person learning, but also transitioned to middle school during a chaotic period of teacher vacancies and rising absenteeism.

The 2023-24 results reflect the last tests administered before federal COVID relief funds run out. Districts must allocate any remaining funds by the end of September — a cutoff that is expected to cause further disruption as districts eliminate staff and programs aimed at learning recovery.

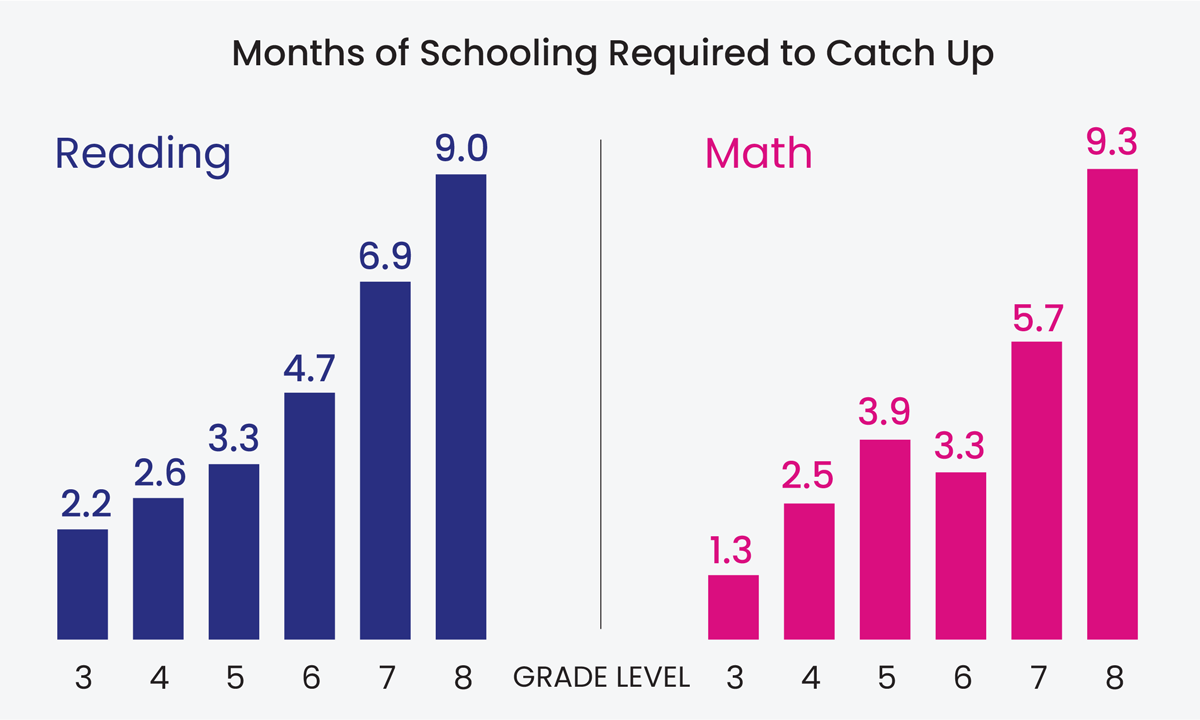

Older students don’t make gains as quickly as younger kids and will have to work harder to catch up, the researchers said. At the same time, the effects of the pandemic “continue to reverberate” for children in the early elementary grades, many of whom missed out on preschool because of COVID. On average, students need at least four extra months of schooling to catch up.

“It’s not fun to continue to bring this bad news to the education community, and I certainly wish it was a brighter story to tell,” said Karyn Lewis, director of research and policy partnerships for NWEA. “It is pretty frustrating for us, and I’m sure very disheartening for folks on the ground that are still working very hard to help kids recover.”

Thus far, only two states, California and Colorado, have asked officials for extra time to spend the diminishing relief funds that remain, according to the U.S. Department of Education. That means the question for most leaders is how to keep paying for extra tutoring and staffing levels for students still learning below grade level — especially those belonging to groups that weren’t meeting expectations before the pandemic.

Relief money “made a difference, but it certainly did not eliminate the learning loss,” said Dan Goldhaber, director of the Center for Analysis of Longitudinal Data in Education Research. A recent paper he authored showed that recovery linked to those dollars was small, in part because the federal government gave districts few restrictions on how to spend it.

The American Rescue Plan’s requirement that districts devote 20% of the $122 billion toward reversing learning decline was “super loosey goosey in terms of what that actually meant, how it was measured and what programs counted,” he said.

Some districts that hired teaching assistants to give students additional practice in reading and math have now lost those positions. Dothan Preparatory Academy in Alabama, a seventh- and eighth-grade school, had several staff members who gave students “a few extra lessons” throughout the day based on their MAP scores, said Charles Longshore, an assistant principal. Now those positions are gone.

He hopes a new sixth grade academy opening next month will better prepare kids for grade-level material. Two years ago, when he joined the Dothan City Schools, just north of the Florida Panhandle, he attended a districtwide administrator meeting where every school’s data was posted on the walls.

He remembers looking at elementary school scores with “really low” student proficiency rates of roughly 20% to 30%; teachers have been trying to fill those gaps ever since.

“We’re trying to go backwards to go forwards,” he said. “What third, fourth and fifth grade standards did you miss that are essential for your understanding of seventh and eighth grade standards?”

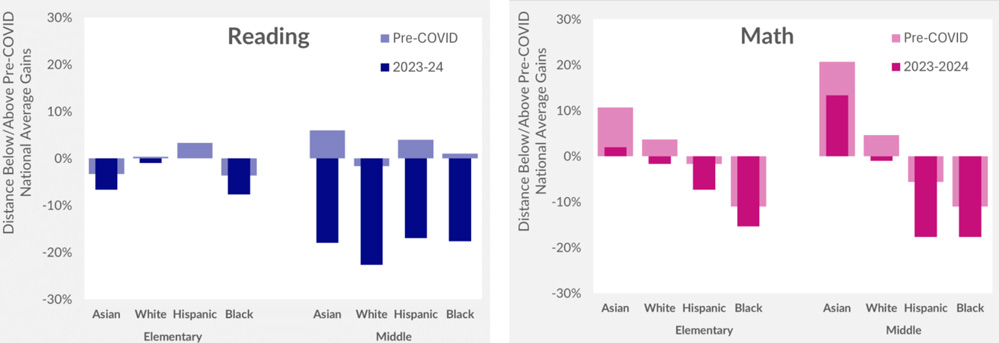

The NWEA results show achievement gaps continuing to widen. For example, Asian students are showing some growth, but made fewer gains in math last year than during the pre-COVID years. White, Black and Hispanic students, however, continue to lose ground. In both elementary and middle school, Hispanic students need the most additional instruction to reach pre-COVID levels, the data shows.

In reading, the gap between pre-pandemic growth and current trends widened by an average of 36%, compared with 18% in math. It’s possible, NWEA’s Lewis added, that districts focused extra recovery efforts on math because initial data on learning loss showed those declines to be the most severe.

But that’s left many students without the reading skills to tackle harder books and vocabulary as they move into high school, said Rebecca Kockler, who leads Reading Reimagined, a project of the nonprofit Advanced Education Research and Development Fund. The organization is funding research to find which literacy strategies work with adolescents, who are easily turned off by books intended for young kids.

The pandemic, she said, only exacerbated a longstanding literacy problem for older students.

“About 30% of American high schoolers for 30 years have been proficient readers, and that really hasn’t changed,” said Kockler, a former Louisiana assistant superintendent who oversaw a redesign of the state’s reading program. “It’s always the hardest to move middle school reading results, and even some of the success we would see in fourth grade didn’t always carry up into middle school.”

School closures were especially hard on students with learning disabilities. Both of Tracy Compton’s daughters, who are entering fifth and seventh grade this fall, have dyslexia and didn’t receive services during the pandemic when they were in the Fairfax County Public Schools in Virginia.

“The time they were learning to read was during the school board’s shutdown of schools,” she said. Under a federal civil rights agreement, the Fairfax district still pays for makeup services with a private tutor.

But Compton also moved to a Massachusetts district where she feels her girls are getting the support they need, like access to audio books and noise-canceling headphones during tests to help them focus. “They have made progress, but [have] not fully recovered,” she said.

She said too many parents don’t know their children are behind.

“They see the report card with A’s or whatever and think all is fine,” she said. “They don’t know where else to check and how to weigh things like standardized tests.”

That’s likely because different tests often tell different stories. The MAP results, for example, are worse than what many states have reported about student performance on their own assessments, which are used for accountability.

Several states last year noted at least partial recovery, and a few showed students had even reached or were exceeding 2019 scores. Lewis explained that state tests measure the “blunt designation between proficient or not,” while MAP tests capture the full spectrum of student achievement levels during the school year.

Districts, particularly low-income districts that received the most funding, need to contend with the latest snapshots of students’ learning as they adjust to the end of federal relief funds, Goldhaber said.

“How districts go about dealing with the fiscal cliff is going to have pretty significant consequences, particularly for the kids that were most impacted by the pandemic,” he said. If districts have to lay off staff — and newer teachers are the first to go — they should limit the impact on the neediest students. “They’ll be shuffling teachers within districts, and that shuffle itself is harmful for student achievement.”

As more time passes since the pandemic, Lewis added that school leaders might be tempted to stop comparing their students’ performance to pre-COVID levels, when states were making progress in closing achievement gaps.

“What keeps me up at night is this idea that these persistent achievement gaps are inevitable, that this is just how it’s going to be,” she said. “I don’t think that’s the case, but I do think it takes innovation and creative thinking … to get us out of this mess.”

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)