Science of Reading Push Helped Some States Exceed Pre-Pandemic Performance

Brown University analysis of test data shows that ‘recovery is possible,’ but many states lag behind.

Get stories like this delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

In 2019, Westcliffe Elementary in Greenville, South Carolina, got troubling news: It was one of 265 schools in the state where more than a third of third graders failed to meet literacy standards.

Then the pandemic hit and “there were bigger fish to fry,” said Principal Beth Farmer.

But the state had a plan.

Teachers in those schools would receive two years of training in what’s known as the science of reading and use a new curriculum with explicit phonics instruction. Farmer has already seen the payoff: Seventy-five percent of third graders met the goal this year, with similar improvement in fourth and fifth grades.

“What appeared to be some penalty … has ended up being a gift,” she said.

The progress sunk in when she recently talked to a student after a quiz. “She said, ‘I was reading 14 words per minute, and now I can read 43 words per minute.’ When a kid can verbalize that to you, that’s real impact.”

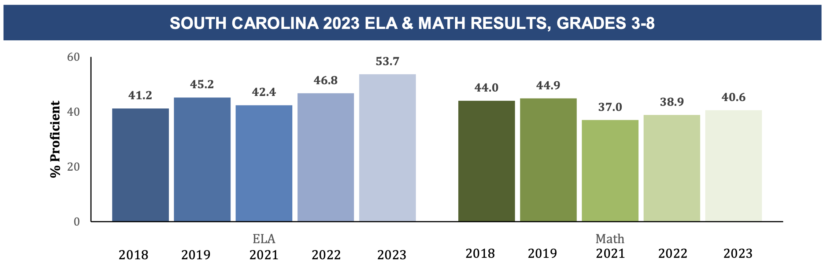

Greenville, with roughly 77,000 students, is South Carolina’s largest district, so the results figure significantly into the state’s overall average. Fifty-four percent of third through eighth graders statewide scored proficient or above this year in English language arts — a big jump from the 45% of students at that level in 2019.

While most states remain behind, South Carolina and three others — Iowa, Mississippi and Tennessee — are recovering from or exceeding COVID-related declines in reading, according to researchers at Brown University. Iowa and Mississippi have also surpassed their 2019 performance in math. Experts say improvements in literacy instruction and an accelerated return to in-person learning are among the key policy decisions contributing to the rebound.

“I am encouraged to see some states surpassing 2019,” said economist Emily Oster, who leads Brown’s COVID-19 School Data Hub. “This suggests substantial recovery is possible, and it provides an opportunity for learning.”

She said it’s “crucial” to understand what those states have done right.

In Iowa, more than 80% of schools offered in-person learning during the 2020-21 school year, according to state officials. In January of 2021, Gov. Kim Reynolds signed a law mandating that schools offer families in-person learning five days a week.

That’s likely one reason why the achievement declines in Iowa were not as steep as those in other states, said Heather Doe, a spokeswoman for the Iowa Department of Education. Between 2019 and 2021, the proficiency rate in English language arts dropped just 2 percentage points, compared with at least twice that much in several other states.

Once more state results are released, Oster plans to match the data with the length of time schools were closed during the 2020-21 school year, as she did last year. The overall takeaway from the previous report was that states where schools were closed longer saw bigger drops in proficiency — as high as 20%.

In the other states, leaders overhauled the way students learn to read, a shift that is now showing up in test results.

South Carolina and Mississippi were among the first states to adopt reform efforts that included a strong emphasis on foundational reading skills.

The turnaround in Mississippi — which in 2019 saw a dramatic leap in fourth grade reading scores on the National Assessment of Educational Progress — has garnered much attention and analysis. But a similar push was underway in the Palmetto State.

The state assigned reading specialists to schools that needed to improve, like Westcliffe. And it gave districts a list of recommended curricula. Greenville chose a program from Savvas Learning Company, which Jeff McCoy, the district’s associate superintendent for academics, described as more “scripted” than the district’s prior approach.

“We recognized that phonics was a missing component,” he said.

The 2023-24 state budget passed this year included $39 million to make a highly regarded training course — Language Essentials for Teachers of Reading and Spelling — available to all K-3 teachers.

Tennessee is a more recent addition to the states requiring training and curriculum on foundational reading skills. Its literacy law passed in 2020. The state also used relief funds for summer learning and high-dosage tutoring.

Dale Chu, a fellow with the conservative Thomas B. Fordham Institute and a policy consultant who focuses on assessment, sees an additional reason for achievement gains in Tennessee: Despite the pandemic, the state was less divided over education.

“Unlike any other state, they’ve largely had bipartisan continuity on education policy across three administrations,” he said.

Parent advocate Sonya Thomas, executive director of Nashville Propel, said the scores are good news for students in the early grades since Tennessee “spent several decades” near the bottom in most educational rankings. But she’s less optimistic about older students’ opportunities to catch up. Many, she said, are “several grade levels behind.”

‘Give this some time’

Despite the positive developments, researchers and testing experts urge caution about interpreting the increase in proficiency rates as a sign of true recovery.

Scott Marion, president and executive director of the Center for Assessment, said Oster provides “a pretty useful look” at where states stand. But assessments aren’t comparable across states; what counts as proficient in one isn’t necessarily the same in another.

Overall proficiency rates also tell just part of the story. In South Carolina, for example, racial achievement gaps haven’t changed much. In 2018, there was a 45 percentage point difference in proficiency rates between Asian and Black students in English language arts. Now it’s 43 points. In math, the gap has actually increased — from 52 to 54 percentage points.

Additionally, some students never cross the threshold from one achievement category to the next, in terms of going from “does not meet expectations” to “approaches expectations,” said Dan Goldhaber, director of the Center for Analysis of Longitudinal Data in Education Research at the American Institutes for Research.

“I’m particularly worried about kids at the bottom, who were unlikely to be proficient before or after the pandemic,” he said.

In most states, proficiency rates in reading are still stuck below pre-pandemic levels. Scores in math are headed in the right direction; nearly all are “making progress,” according to Oster.

But her summary serves as a reminder of how long it will take for some students to rebound, Chu said. “If you look at learning loss and what schools need to do to catch up, there’s no precedent,” he said. “The [education] system has never done this before.”

Despite billions in federal relief funds for tutoring, summer school and extra staff in the classroom, five states — Arkansas, Delaware, Massachusetts, Minnesota and Nevada — have continued to lose ground in reading since 2019. The percentage of students scoring proficient or above dropped this year.

Minnesota, for one, is several years behind states like Mississippi in requiring reading instruction to include phonics. Just this year, the state passed the READ Act, legislation that provides $70 million for “science of reading” training and curriculum.

Last month, the Minneapolis district’s disappointing literacy results sparked a sobering discussion at a school board meeting.

“I would not say that it is a privilege to share this data,” Sarah Hunter, the district’s executive director of strategic initiatives, told the board. Since 2022, the percentage of district students who scored proficient decreased from 42% to 41% — the third consecutive year of decline. Board members blamed the pandemic and urged patience.

“I know our scores are still low,” said Ira Jourdain. “Let’s give this some time.”

Such comments left some advocates feeling uneasy.

“How do we hold districts accountable?” asked Josh Crosson, executive director of EdAllies in Minneapolis. “We have a lot of funding that goes to schools that aren’t doing well in literacy.”

He thinks the READ Act is a step forward, but doesn’t do enough to integrate literacy training and teacher preparation.

“I don’t think we’re going to see improved outcomes in these first couple months,” he said. “I think we’re going to see improved outcomes in the next few years.”

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)