Student Reporters Could be the Fix Local News Needs. Let’s Give Them the Legal Protections to Cover More than Pep Rallies and STEM Competitions

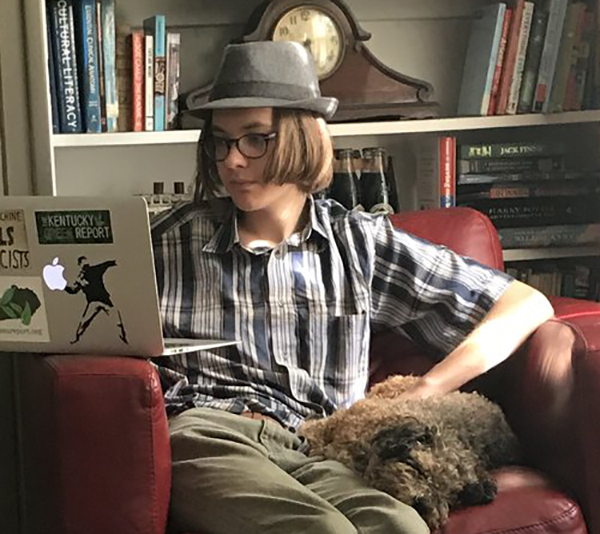

When Satchel Walton first saw the Hitler quotes on police training slides, his journalistic instincts kicked in. He filed an open records request with the Kentucky State Police and reached out to a spokesperson for comment. It took several calls and emails to the department before he got a response, but hours later “KSP training slideshow quotes Hitler, advocates ‘ruthless’ violence” went live on Manual Redeye, the student newspaper of duPont Manual High School. Three days later, the police commissioner, a 33-year veteran of the department, resigned amid the national attention the story received.

This wasn’t a fluke. The Louisville-based school is an award-winning journalism magnet in the state. The teachers and administrators there expect students to produce hard-hitting journalism. They hold a high bar of excellence and encourage watchdog stories that expose faults, deception and misdeeds in the community.

Stories like Walton’s, and other ones from Cedar Blueprints (Athens, Ga.) and Theogony (Alexandria, Va.), are proof of what happens when you take young journalists seriously. But not every kid has that opportunity.

There are hundreds of other schools in Kentucky that don’t have supportive administrators. The young reporters at those schools face the threat of censorship with every story they publish. In fact, they are so used to hearing “no” or “stop,” they’ve internalized self-censorship and resigned themselves to covering only pep rallies and STEM competitions.

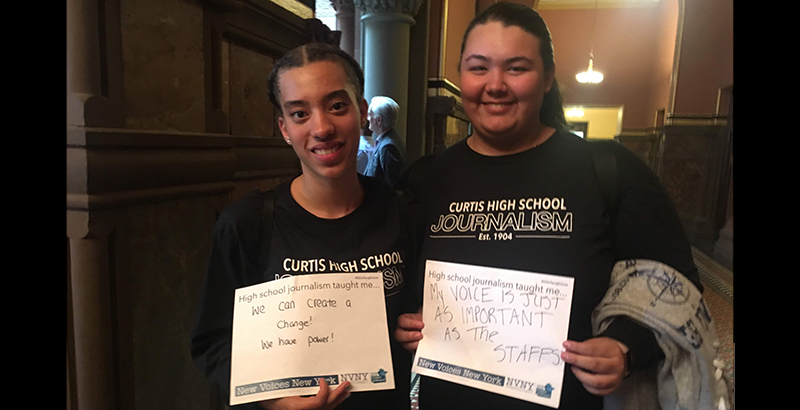

Having the opportunity to learn how to be civically engaged through journalism shouldn’t be about luck. This is why all states need to pass New Voices legislation that provides full First Amendment rights to all journalists

Right now in most of the country, student journalists have fewer First Amendment rights than the other teens at their school. It wasn’t always this way. In 1969, the Supreme Court ruled in Tinker vs Des Moines that students didn’t “shed their constitutional rights to freedom of speech or expression at the schoolhouse gate.” Then, 30 years ago, the Supreme Court made a more restrictive ruling in Hazelwood vs. Kuhlmeier, which essentially opened the door to unguided censorship in school publications.

Currently 14 states have New Voices laws that effectively reverse Hazelwood and return them to rule under Tinker. With the guidance of the Student Press Law Center student- and teacher-led coalitions are actively lobbying local lawmakers and speaking at state hearings to pass legislation across the country. As we begin 2021, we need to assess the remarkable role young reporters play in our communities and pass such legislation in every state.

Just like their counterparts in professional newsrooms, student journalists have been working from home. On top of classes, SAT prep and college applications, they are covering Black Lives Matter rallies at school, exploring staff diversity and mining detention data for evidence of systemic racism. They were the first — and in some cases, the only — journalists to cover student mental health issues and distance learning challenges, among other pressing topics. After what they had to do this year, we can’t ask them to go back to covering pep rallies.

Since March, the SPLC hotline has been hearing from student journalists who are getting blocked by administrators as they try to report on the student body’s adoption of masks, get access to where athletes practice or request the school’s COVID-positivity rates. By obstructing reporter’s access, administrators are actively keeping vital information from families that could save lives. Especially at a time when local newsrooms are reducing staff sizes, student-produced news sites are essential to the community.

New Voices had tremendous momentum last year. Progress was made in nine states where bills were considered, including Colorado, where a 30-year-old bill was updated to protect advisers and digital media. We need to move that needle further forward in 2021. We can’t ask student journalists to do this alone. They need your help.

As educators, school administrators and education policy makers, we need to support the New Voices initiatives in our states. We need to recognize that student journalism is community journalism. There has been a shift in the journalism education world to start recognizing college and high school reporters as journalists, not student journalists. That’s great, but we need to give the work they produce the same recognition. Elevating their status without paying attention to their work is no more than a pat on the head.

For so long administrators told us students were too immature to handle press freedoms. They said it would be the Wild West if teens could publish whatever they want. Here’s the thing: students are doing that anyway — on their blogs, on social media, in chat forums. But student journalists are not doing that. They are guided by advisers who hold them accountable to the Society of Professional Journalists Code of Ethics — the same code followed by journalists at The Wall Street Journal, The Associated Press, Chicago Tribune, LA Times and every other professional newsroom in the country. Yes, student journalists make mistakes, but so do the pros.

Since Walton’s story on the Kentucky police force came out, his newsroom scored an exclusive interview with the governor, who denounced the “Warrior Mindset” in law enforcement training. Acknowledging their work adds it to the wider national conversation about racism and police brutality.

Imagine if we gave this recognition, this respect, to all of the reporters and editors in this country who we are teaching in our classrooms. Think about how accepting these young journalists as active and valuable members of our society could prepare them for a lifetime of community engagement and keep our local news deserts informed.

Katina Paron is the author of “A NewsHound’s Guide to Student Journalism,” the manager of Teach for Chicago Journalism at Medill and an active member of New Voices New York.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)