Strong Link in Big City Districts’ 4th-Grade Math Scores to School Closures

Urban districts that spent the majority of 2020-21 learning remotely lost more ground in fourth-grade math on average than those that reopened sooner

Get stories like this delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

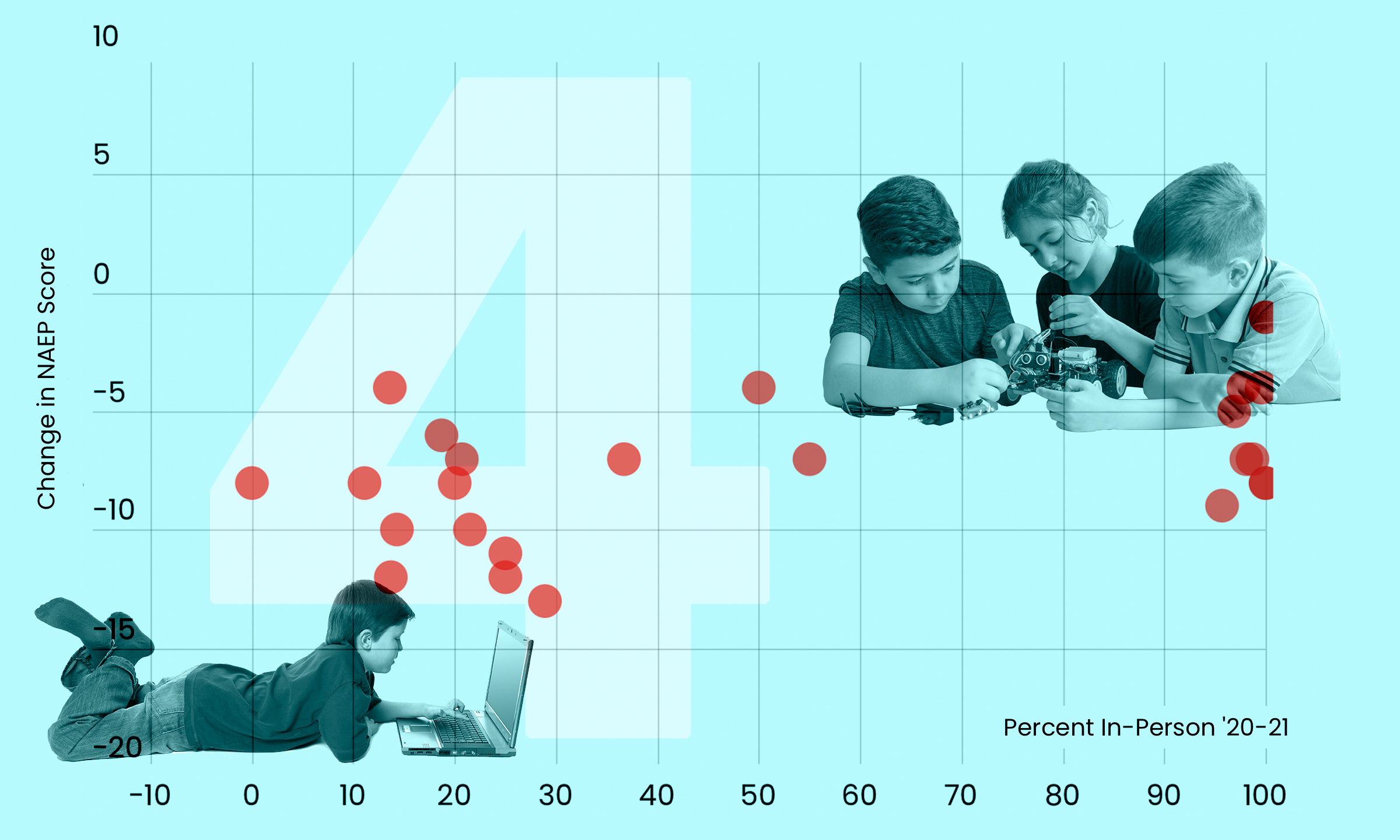

The size of younger students’ learning setbacks in math during the pandemic varied in accordance with how long their school system stayed closed in 2020-21, an analysis by The 74 of district-level National Assessment of Educational Progress data shows.

Districts that spent the majority of that year learning remotely tended to lose more ground in fourth-grade math scores than districts that reopened sooner. Every 10 additional days of school closures was associated with a roughly 0.2-point loss on NAEP from 2019 to 2022. The pattern was statistically significant and held even when controlling for the share of students eligible for free- or reduced-price lunch, a proxy for poverty.

“The districts with more remote learning have larger test score losses,” said Emily Oster, a Brown University economics professor who has tracked school closures through the pandemic.

“It’s pretty consistent with what we have seen up until now,” added the researcher, an early and ardent supporter of reopening schools during the pandemic shutdown whose positions were sometimes vilified.

The finding adds to the mounting evidence that online learning during the pandemic had a negative impact on student learning outcomes, even while there is renewed debate over how strongly the 2022 NAEP scores reflect it. The highly anticipated results released Monday showed the largest drops ever recorded in 4th and 8th grade math.

Peggy Carr, head of the U.S. Department of Education center that administers NAEP exams, played down any possible relationships between school closures and test results.

“There is nothing in this data that tells us there is a measurable difference between states and districts based solely on how long schools were closed,” she said during a Friday press conference.

Oster, who also conducted her own analyses of the relationship between remote learning and NAEP results, called the National Center for Education Statistics director’s statement “odd” and “not very consistent with what we are seeing in the data.”

However, she acknowledged that there is an element of truth to Carr’s words.

“Maybe what they’re saying is that [school closure] is not the only determinant, and that’s right. It is not the case that there is a straight line between remoteness and test score losses,” she said.

An NCES spokesperson affirmed that stance Tuesday, denying any “simple direct relationship between duration of remote learning and score declines based on NAEP results” in a statement emailed to The 74.

“Controlling for free- or reduced-price lunch is helpful but not sufficient,” the spokesperson continued. “NCES will be conducting analyses that conform to the highest statistical standards, consider multiple variables and link data collected by NCES to other high quality datasets.”

On the whole, results from what’s known as the Nation’s Report Card revealed the stark drop offs in math and a slide in reading since 2019, the last time the exam was administered. Some individual school systems, however, performed better than expected, including Los Angeles, among the districts which stayed in remote learning the longest and which saw improvements in reading for fourth graders and in both reading and math for eighth graders.

Since the release of NAEP results on Monday, researchers and news outlets have conducted several analyses correlating scores with length of school closures and found moderate, statistically significant links. However, those analyses have largely focused on state data, an approach some experts warn against because it lumps districts that reopened quickly with those that stayed shuttered much longer.

“Within states, there’s a lot of heterogeneity in terms of closure policies,” said Tom Loveless, a longtime education researcher who formerly led the Brookings Institution’s Brown Center on Education Policy.

“Looking at district data is superior to looking at state data because that’s where the [reopening] decisions were made,” he said.

The 74 took the district-level approach, crunching data from a sample of large urban school systems included in the NAEP release. Their scores were then matched with closure data from Oster’s COVID-19 School Data Hub, which tracked the percentage of the 2020-21 school year that districts offered remote, hybrid or in-person instruction. From the full sample of 26 school systems, Fresno was removed because it had no publicized 2022 NAEP scores and New York City, the nation’s largest school district, and Shelby County, Tennessee were excluded because they had no district-level school closure data available in the Hub.

Among the 23 remaining school systems, fourth-grade math was the only subject with a statistically significant relationship between district performance and time spent in remote learning. There were weak correlations in fourth-grade reading and eighth-grade math and no association for eighth-grade reading.

“It was very hard for the little kids to focus on Zoom,” said Robin Lake, director of the Center on Reinventing Public Education. “It wouldn’t surprise me if the younger students saw more of an impact on literacy skills and early foundational computational skills.”

Her research group analyzed data on the effects of school closures, finding severe negative academic impacts, especially for younger students and those living in poverty.

“Schools stayed closed too long, especially in urban areas,” Lake said, noting that her judgment is much easier to make now with the benefit of hindsight as opposed to during the height of COVID when the science on infections and transmissibility was still coming into focus.

The variation in the NAEP results represents “shades of badness,” she said. “Some states are celebrating not being as bad as other states, but nobody has much to celebrate here.”

NAEP results must be interpreted carefully, experts caution. They are built to show how students are doing, not to explain the reasons behind their performance, Loveless said. (He compared the exam to a thermometer: “It can tell you if you have a temperature, but it can’t tell you why.”)

However, the exam is also the only U.S. test administered to students in all 50 states, making it “the only game in town when it comes to comparing across states,” said the former Brookings Institution researcher.

The 74 analysis, he said, “makes an addition” to the continued dialogue on the impacts of school closures during the pandemic.

Now, with the extent of pandemic missed learning coming into greater focus across the nation, Lake said, it’s time to hone in on how to respond.

“We’ve just got a lot of work to do to give kids back what they were owed, both academically and developmentally.”

Oster agreed that it may be time to put aside reopening showdowns and instead work toward recovery.

“There is a very reasonable desire to move on from the discussion of, ‘How important were school closures?’ into, ‘How do we fix this?’” she said. “I’m quite sympathetic to that desire to move on.”

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)