Story of 1939 VA Library Sit-in Reinforces Today’s Fight for Access to Books

Guernsey & Owens: Just as 5 young Black men protested for educational freedom, young people are raising their voices for the right to read

Get stories like this delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

In the summer of 1939, an event unfolded in Alexandria, Virginia, that represents a fight for educational access and freedom that continues to this day.

On the morning of Aug. 21, 1939, five young Black men entered Alexandria’s only public library and sat down at tables to read books they had selected from the shelves. The head librarian, following the library’s “whites only” policy, called the city manager. He had the five men arrested. They were charged with disorderly conduct, even though they did nothing other than read quietly. The charges were not dismissed until 2019, long after the men had passed away.

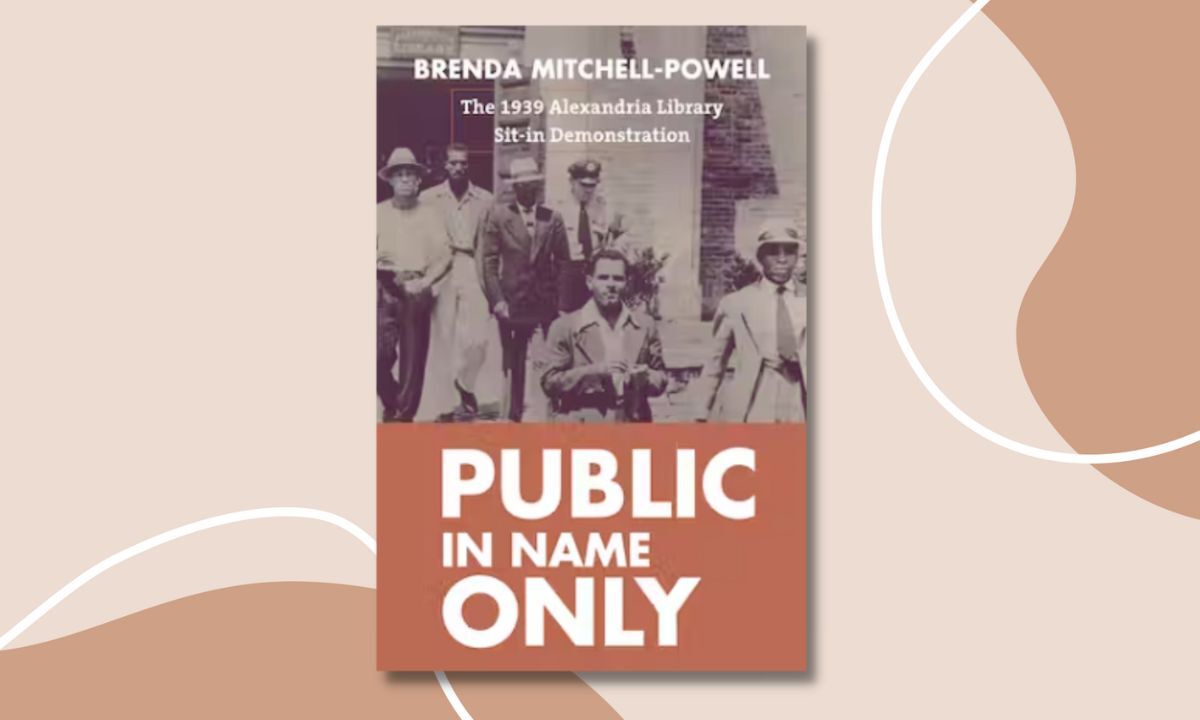

The event was, in fact, an organized sit-in, the first of its kind in a public library. It is now the subject of a new book, Public in Name Only, written by former librarian Brenda Mitchell-Powell and published last fall by the University of Massachusetts Press. For decades, the story of these five men — one as young as 18 — was barely known. Most residents of Virginia, let alone the United States, have never heard of it. Today — as educational spaces like libraries are under attack, and as questions about race and education access become central to the debate over what kind of country the United States should be — the story of the Alexandria library sit-in needs to be heard.

Obviously, there are key differences between current injustices and the Jim Crow policies that denied students access to libraries and schools based on their skin color — policies the Supreme Court ruled unconstitutional more than 50 years ago. Today, debates rage about what books can be stocked on library shelves or introduced to students in public school classrooms. This situation feels more subtle, not to mention complicated by issues such as at what age it is appropriate for a child to have access to certain materials.

But the story of these five young men in Alexandria in 1939 is a reminder of the unfairness and infringement of rights that come when one group of people dictates what other people are allowed to see, read, absorb and learn.

With the benefit of Mitchell-Powell’s scholarship, as well as decades of work by the Alexandria Black History Museum, the Alexandria Library and other researchers, new details about the sit-in are now coming to light. The story starts with a 26-year-old Black lawyer named Samuel Tucker, who grew up in Alexandria in the 1920s and early 1930s. At that time, if Black students in the city wanted to attend high school, they had to cross the state line to attend school in Washington, D.C. Tucker, educated at Howard University, passed the Virginia bar exam without even attending law school and was determined, along with his younger brother, Otto, to get a library card and check out books at the newly opened public library down the street from their house.

The Tuckers organized a peaceful sit-in to show how the whites-only policies of the day were restricting their rights — an early example of the way young people today are challenging systems that limit how and what they are allowed to learn. On that hot day in August, they executed their plan, resulting in Otto and four other young men being escorted out by two police officers and exposing the ugliness of the library’s policy. More than half a dozen newspapers covered the event.

The eventual outcome of this sit-in was, as Mitchell-Powell writes, “a partial victory and a defeat.” Delaying tactics by judges in the city, along with the distractions of the start of World War II just a few weeks later, ruined any chance of a clear ruling on the constitutional rights of these young men to use the public library. City officials, apparently wishing that the issue would just go away, rushed the construction of what was labeled the “colored library.” That library Mitchell-Powell calls “a civil rights loss.” It was a one-room building with one-fifth the number of books, very few of which related to the interests and lives of those in the city’s African American community, and which were in generally rough condition. It was not until 1962, 23 years later, that Alexandria’s library system was opened to all.

Similar instances of closed doors and exclusion were happening across the South, and less blatant versions dotted the North, according to Not Free, Not for All: Public Libraries in the Age of Jim Crow, a book recently published by University of Arizona professor Cheryl Knott. This denial of educational opportunity affected generations of residents, and as part of a constellation of other discriminatory acts, reduced Black residents’ chances for building knowledge and skills for themselves, as well as their children and grandchildren.

Today, some conservative groups are pushing libraries and schools to remove books related to race, gender and sexual orientation. Some libraries fear cuts in funding if they don’t capitulate. In this, we see the outlines of a contemporary version of denying certain people — those who look and think differently, those on the margins or those who cannot afford to buy books — access to knowledge and ideas. Naturally, institutions like libraries also need to respect parents’ rights and ensure that young children do not stumble onto inappropriate material designed for teens and adults; libraries and schools, and the professionals within them, know they have a responsibility to set restrictions and guardrails. But when one group following a particular viewpoint is setting the terms for an entire community, dictating who is allowed to read what and which reading materials should be available, we hear echoes from the days of more blatant racial and gender discrimination in the education system.

Today, the battle over who gets to make decisions about access to books and media persists. Just as Samuel Tucker and his friends protested for educational freedom in 1939, today’s youth are raising their voices for the right to read. Power struggles over how and whether teachers should address topics deemed divisive close off opportunities for learning when, instead, libraries and schools should be opening them up. Without learning lessons from the past, American society risks reverting to the days when whole populations of students and families were shut out. The story of the Alexandria library sit-in could not come at a better time.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)