Startup Computer Science High School in the Hard-Hit Bronx Made Quick Leap to Remote Learning

By Brendan Lowe | July 13, 2020

It was just after 5:30 p.m. on Sunday, March 15, when New York City Mayor Bill de Blasio announced that the nation’s largest school district would transition to remote learning until at least April 20. Chaos ensued, with many teachers still reporting to their buildings the next day and the day after. The Department of Education began ordering 300,000 iPads. Teachers were allowed to use Zoom for instruction, until they weren’t, and then they were again.

At Comp Sci High in the Bronx, however, remote learning started about 12 hours after the mayor’s announcement. The school’s principal said his staff had spent the previous two weeks developing an e-learning plan, and students already had Chromebooks and were familiar with checking their email and using Google Classroom.

“It’s gone well, under the circumstances,” said David Noah, the founding school leader. “I don’t want to minimize all of the struggles the kids and community have been through. Teachers have been super heroic, but it’s gone well — certainly by comparison.”

The school, formally the Urban Assembly Charter High School for Computer Science, has some inherent advantages. It opened in 2018-19 with a ninth grade, and it now serves about 220 students across grades 9 and 10. It’s a charter school, with non-union staff and all of the flexibilities that come with the designation. And, among other features, it’s a technology-focused school where students take computer science courses all four years.

That doesn’t mean, however, that the school’s transition to remote learning was flawless.

“The quality of assignments was terrible in the first two weeks,” said Noah, in a tone more understanding than accusatory. “We’re a newish school, and we’re very much in the habit of ‘OK, the way we figure things out is by doing and trying it and changing them,’ which is very stressful, but fortunately [the staff] were very used to that stress.”

The school launched its remote learning program immediately, Noah said, to maintain continuity for its students and families during the pandemic. Many students’ parents are frontline health care workers. Almost all students are Black or Latino, and most come from low-income households. The school is located in one of the hardest-hit areas of what was the hardest-hit city in the world; both students and staff have lost parents to COVID-19.

Support for families came in many forms. Noah and other school staff spent several days early on delivering hotspots and replacement Chromebooks to students’ apartment buildings — the school ordered 60 backup devices on March 1, two weeks before de Blasio closed schools. Families were asked each week to fill out a survey about their needs, and the staff raised funds to provide gift cards for groceries and emergency supplies.

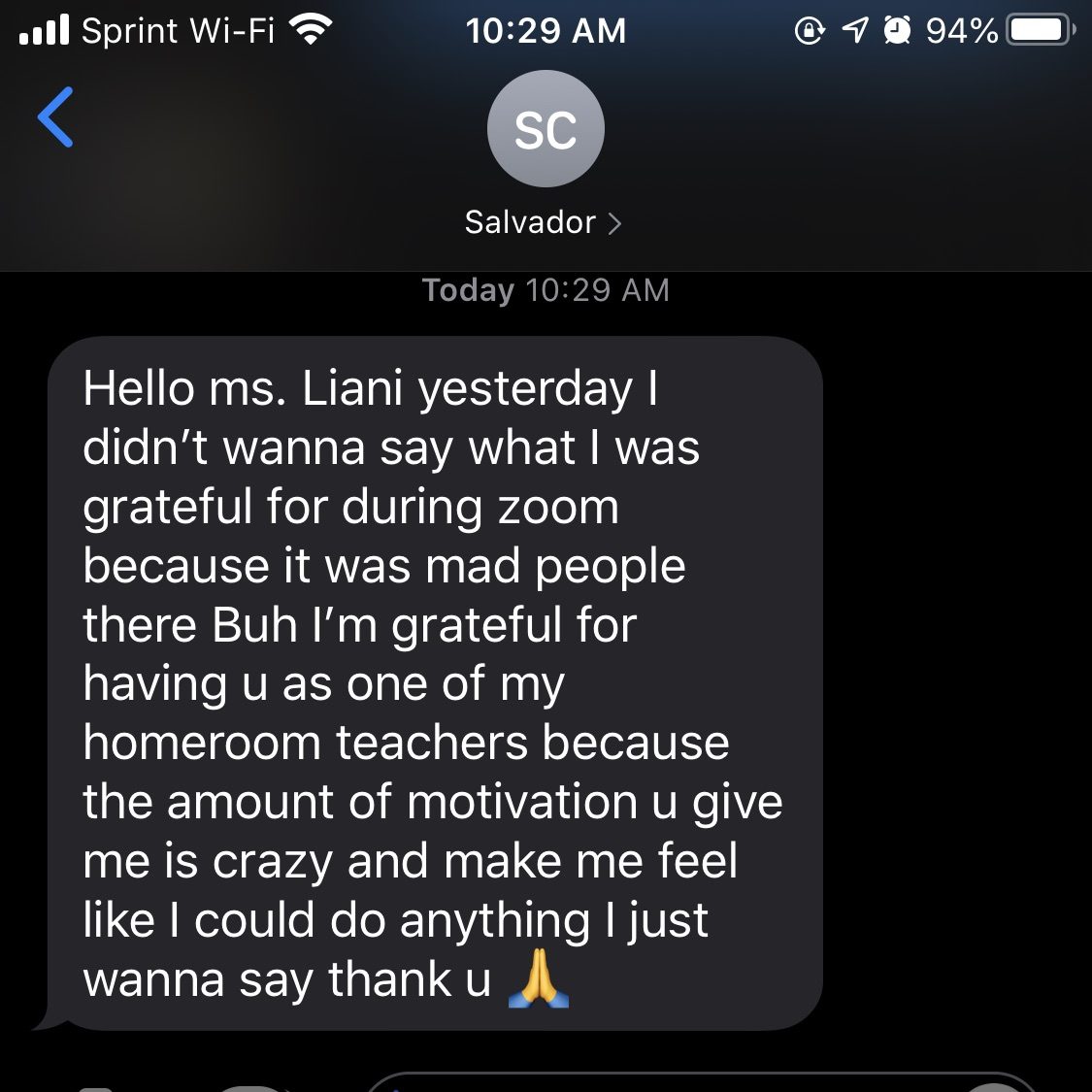

For students, the support was as constant as students permitted, said Eddy Mosley, who teaches computer science and an advisory, which is akin to a life skills class. Even before the pandemic, Mosley and his 29 advisees had maintained an active group text chain, and one-on-one texts and calls were added to a mix that also included virtual office hours and Zoom calls. Then there’s email. Mosley said students collectively sent him between five and 20 emails an hour.

The goal, he said, was to maintain as strong a school culture as possible and help lift students up during this crisis.

“One of the kids I’m talking to right now,” Mosley said, referring to an ongoing text chain earlier this year, “he’s complaining because his grandfather just came home [from the hospital] from having a stroke and his mom just had a baby and he’s essentially babysitting his grandfather all day. Like, ‘I can’t do anything because my grandfather needs me. If he slips out the chair and falls, that’s on me.’ What am I supposed to say to that? So just kind of being there for kids and giving them someone to talk to, because it’s hard, and [sometimes] there’s not much we can do.”

How much schools can and should do — the expectations they should maintain for students — became a hot topic. Districts in several states ended their school years early, such as in Georgia’s Bibb County, where, according to the superintendent, many parents essentially said, “We were stressed.” In New York City, the Department of Education kept its full school year and even turned its spring break into instructional days, while also loosening its grading policy. The mayor announced on May 19 that some 178,000 NYC public school students would return for remote summer school because of the learning disruption wrought by the virus.

The varied response to the crisis meant there were days when DJ Hamilton, a sophomore at Comp Sci High, lamented the three or four hours of work he had to do each day. He transferred at the start of this school year and was taking an Advanced Placement computer science course. He lives with his grandmother, who tested positive for COVID-19, and he knows that some of his peers attend schools that had very different academic expectations.

“One of my friends told me that his assignment was to give his teacher movie recommendations on Netflix, or a TV show, and then they get a 100,” he said.

After an admittedly tough transition, Hamilton said, he found a schedule that works for him. He went to bed around 6 a.m., slept until 2 p.m., and did his school work until around 6 p.m. He would nap and then play video games for hours. Oftentimes, he said, he would do his easiest assignments between 5 and 6 a.m. before going to bed.

The school also adapted. Comp Sci High already had a mastery-based grading system, which evaluates students by how well they meet the standards, not how many assignments they complete, and an alternative schedule — 9:30 a.m. to 4:40 p.m. for most students — so the shift was minor. Assignments were due by 11:59 p.m., and Noah said 80 percent of what he described as “a pretty ambitious amount of work” was being completed. Teachers had 24 hours to mark in a shared data tracker if students turned in the assignment, which helped advisers monitor whether their students were keeping up with their work and then follow up accordingly.

Some adjustments proved more difficult. Comp Sci High is a work-based learning school, and students are expected to have an internship or job each summer. Before the pandemic struck, Noah said, the school was on pace to place all 220 students. Now, he said, with the New York City summer jobs program only partially restored, the economy reeling and many restrictions still in place, he hopes that as many as 150 students will participate in paid virtual apprenticeships at companies like J.P. Morgan and programs like Project Destined, which teaches digital real estate marketing.

Maintaining high standards in the face of significant challenges — and supporting students to meet those challenges — is, ultimately, why Comp Sci High exists. Noah and 40 percent of his staff formerly worked at Success Academies, the hard-driving, fast-growing New York City charter school network. The founding team designed the school to replicate Success’s strong academic outcomes but not its strict, high-compliance culture where teachers check students’ sock colors.

The team also committed to serving its community in District 12, routinely one of the lowest-performing in the city. The school doesn’t have admissions criteria like test scores or demonstrated proficiency, and parents can text staff pictures of a completed application in order to enroll. One-quarter of its students have special needs, higher than the 19 percent citywide.

So far, at least, the approach seems to be working. Comp Sci High students can wear jogger sweatpants as part of their school uniform, which would count as heresy at most charter schools, and yet their results are strong. Almost all of its ninth-grade students last year took and passed the state graduation exam for Algebra I. The percentage of ninth-grade students earning 10 or more credits — a key metric for students being on track to graduate on time — exceeded the citywide average by 11 points. And all but one teacher returned from the school’s first year, as did 96 percent of its students.

“One of our founding mantras was ‘If we’re not going to be different, what’s the point of founding a school?’” —Principal David Noah

The Comp Sci High staff readily acknowledge that these are early days. They say they will judge their success by economic freedom, as measured by whether its students from the Bronx, where the median annual household income is $37,500, can exceed the citywide average of nearly $61,000 by the time they’re 25.

“One of our founding mantras was ‘If we’re not going to be different, what’s the point of founding a school?’” said Noah, pledging that the high expectations will persist. “Telling kids who are suffering from grave economic inequality and multigenerational racism, ‘Hey, it’s OK, if there’s hardship someone will help you out,’ isn’t necessarily the most realistic message to prepare them for the future.”

Lead Image: Teacher Eddy Mosley speaks with his advisory students in January before Comp Sci High was closed by the coronavirus. Since then, the advisory, which is similar to a life skills class, has maintained an active group text chain. (Brendan Lowe)

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter