Startling Science Scores in California: First-Ever Results Show 4 in 5 Low-Income Black and Latino Students Are Falling Short of New State Standards

A state task force newly assigned to narrowing California’s achievement gap got further proof of the challenges ahead with this month’s first-ever release of the California Science Test scores, showing that less than 1 in 5 low-income black and Latino students met or exceeded the standards.

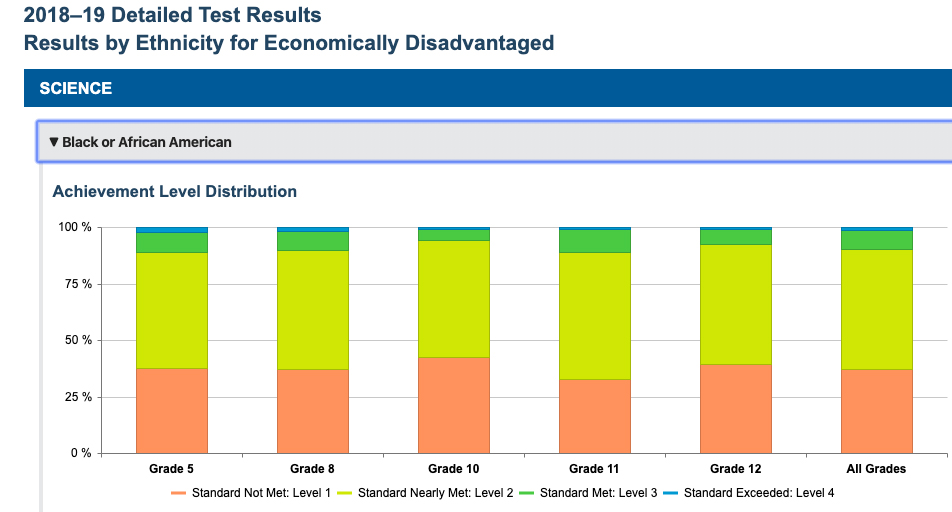

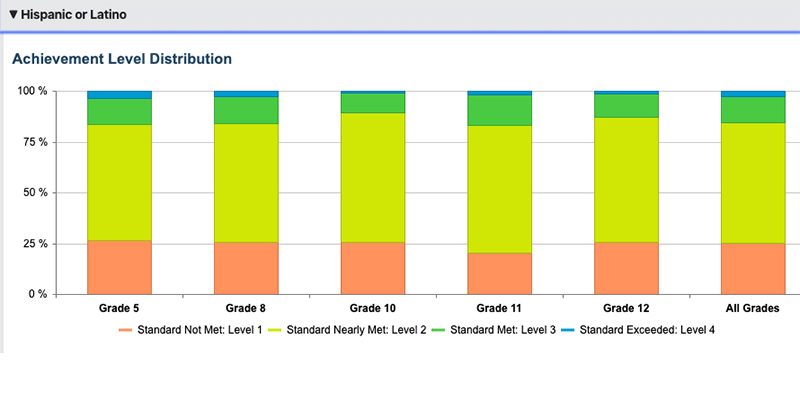

The results released by the California Department of Education show that, across all grades statewide, 9.94 percent of disadvantaged black students and 15.64 percent of disadvantaged Latino students met or exceeded the science standards on the inaugural test known as CAST, compared with 44 percent of non-disadvantaged white students and nearly 60 percent of Asian students.

The results for those student subgroups in Los Angeles Unified School District, the largest in California and the second-largest in the country, closely mirrored the state’s, with 10 percent of low-income black students and 16 percent of low-income Latino students meeting or exceeding the science standards. Only 5 percent of LAUSD’s English learners met or exceeded them, lower than special education students at 8 percent.

LAUSD’s Science Academy STEM Magnet, a middle and high school for gifted and highly gifted students whose enrollment is more than 80 percent white and Asian, had the highest score in the state, with 98.5 percent of its students meeting or exceeding standards.

The new science test, aligned with the Next Generation Science Standards, was taken for the first time last spring by students in grades 5 and 8 and 10 through 12.

“The results confirm the trends we continue to see in other assessment data — that our education systems are failing to support African American, Latinx, English learners, and low-income students to meet California’s Science standards,” Christopher J. Nellum, deputy director of Education Trust–West, said in an email statement Feb. 6, the day the scores were released. “These CAST results do not reflect the promise we must uphold to accelerate academic progress for all students, especially students of color and low-income students.”

Statewide, the 2019 CAST scores showed that nearly 30 percent of students who took the test met or exceeded standards. In Los Angeles Unified, 23 percent of them met or exceeded standards.

Nellum also noted that the results for English learners statewide are alarmingly low, with only 3 percent meeting the standards. The numbers are even worse for the individual grades, with eighth-grade ELLs at 2.3 percent; 10th-graders at 1.1 percent, 11th-graders at 2.2 percent and 12th-graders at 1.38 percent.

“We know these results are not a reflection of student ability; rather, they are a reflection of systems and practices that continue to fail students,” Nellum said.

The CAST scores add another dimension to the dismal results and deep achievement gap seen in the state’s reading and math test scores. The results for the 2018-19 California Assessment of Student Performance and Progress, known as CAASPP, showed that 16 percent of disadvantaged black students and 24 percent of disadvantaged Latino students met or exceeded math standards, while 27 percent of disadvantaged black students and 36 percent of disadvantaged Latinos met or exceeded the standard in reading.

LAUSD’s secondary science coordinator Ayham Dahi said the science test results are “very concerning” but noted that there was little expectation for stronger outcomes given that the new science standards were a major overhaul. He thinks the scores may represent a baseline.

“This is the first time we get to see these results. It was quite a shift from our old ways of instruction and learning,” Dahi said. “We really didn’t know what to expect this year.”

“Our number one goal is to address the needs of all students, that all subgroups have quality support systems in place in schools, and provide targeted intervention for our students to address their needs and to bridge the opportunity gap for our students. That’s the main focus of LAUSD,” he added.

Dahi highlighted that the achievement demands are different now, with students needing to apply learning skills, like argumentation from evidence, investigation and planning, and to use models rather than memorization from the old standards.

The new science test measures the Next Generation Science Standards adopted in 2013 to replace the old standards from 1998. In 2016, the State Board of Education released not a formal curriculum but a framework to help guide teachers with implementation.

Dahi noted that next year will be the first in which science teachers will have curriculum and materials available under the new standards.

“We are going to have for the first time brand-new curriculum, special materials including science kits in our schools that are aligned with the Next Generation Science Standards. Up to this date and for the last four to five years, we didn’t have that. Our teachers had to supplement the [Next Generation Science Standards] with other materials. Next year we don’t have to do that.”

Dahi said they didn’t even know what the CAST was going to look like going into the first exam and that it may be different next year. Despite that, he said the district is very optimistic about students getting better scores next year.

Chelsea Culbert is a high school science teacher at Alliance Susan and Eric Smidt Technology High School in Lincoln Heights in northeast Los Angeles. The school serves more than 90 percent low-income Latino students. Culbert says she has been teaching under the Next Generation Science Standards for the past six years and slightly over 23 percent of her high school students met or exceeded the standards on the new test, above LAUSD’s average of nearly 11 percent of high schoolers meeting or exceeding standards.

Culbert believes that the CAST does not necessarily test students’ knowledge but rather measures more how they apply it. Once students can learn the new science standards in the elementary grades, she said, they will have the skills needed to get better test scores in the secondary grades.

She also noted that the high school grades currently lack an effective science curriculum, which may have contributed to the low scores statewide.

“There is not much curriculum available at all using the new standards,” Culbert said. She had to create her own by using different resources to develop her lessons. “Even what we got this year is not great. At the high school level, there’s nothing awesome that I can say everyone is using, because it doesn’t exist.”

Even though Culbert did not experience a major shift herself, she thinks that for teachers who have been teaching under the old science standards for a long time, adopting the new ones can be a significant struggle.

“If teachers are very used to the old way of teaching and they are not willing or don’t have the resources to change, that’s probably another very big barrier,” she said.

Nellum laid out some recommendations issued by Education Trust–West to close the achievement gap evident in the CAST results, including using the nearly $1 billion in funding allocated by Gov. Gavin Newsom for teacher training to ensure “effective and equitable science standards implementation in high-need school communities.”

“California needs a plan to prepare, recruit and retain many more STEM teachers — especially women and teachers of color,” Nellum said. “School and district leaders should commit to providing robust professional learning opportunities to current and future educators and ensure effective and equitable standards implementation.”

Last year, state Superintendent of Public Instruction Tony Thurmond launched a new initiative to close the achievement gap statewide. He created a working group to look closely at schools throughout the state that have shown success in improving outcomes for African Americans, Latinos and other students of color, while also addressing the recruitment and retention of teachers of color.

Thurmond appointed three co-chairs to lead the Closing the Achievement Gap task force, including Ryan Smith, who recently joined the Partnership for Los Angeles Schools, a nonprofit established in 2007 to manage what were then the district’s lowest-performing schools.

Smith, who serves as chief external officer, told LA School Report in an interview last summer that the answer is not just providing more money to schools.

“It’s how we spend it. As we fight to increase school funding, we need to ensure that funds are used in support of the highest-need schools across our state. We also must also ensure that every student — no matter his or her zip code — is receiving the same type of rigorous and culturally relevant curriculum in class and early and expanded learning opportunities.”

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)