St. Louis NAACP Marshals Local Nonprofits to Help Make Sure Every Child Can Read

'When white America has the flu or a cold, Black America has pneumonia' — 'Right to Read' campaign targets huge disparities in third-grade literacy.

Get stories like this delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

After more than a decade of struggles, nonprofits are leading the charge to help more Black students in St. Louis read at grade level.

The St. Louis NAACP recently launched the “Right to Read” campaign, which focuses on improving proficiency and educational equity for students of color. Its mission: By 2030, all children in the city and county of St. Louis will receive the materials and support they need to help get them reading well by third grade.

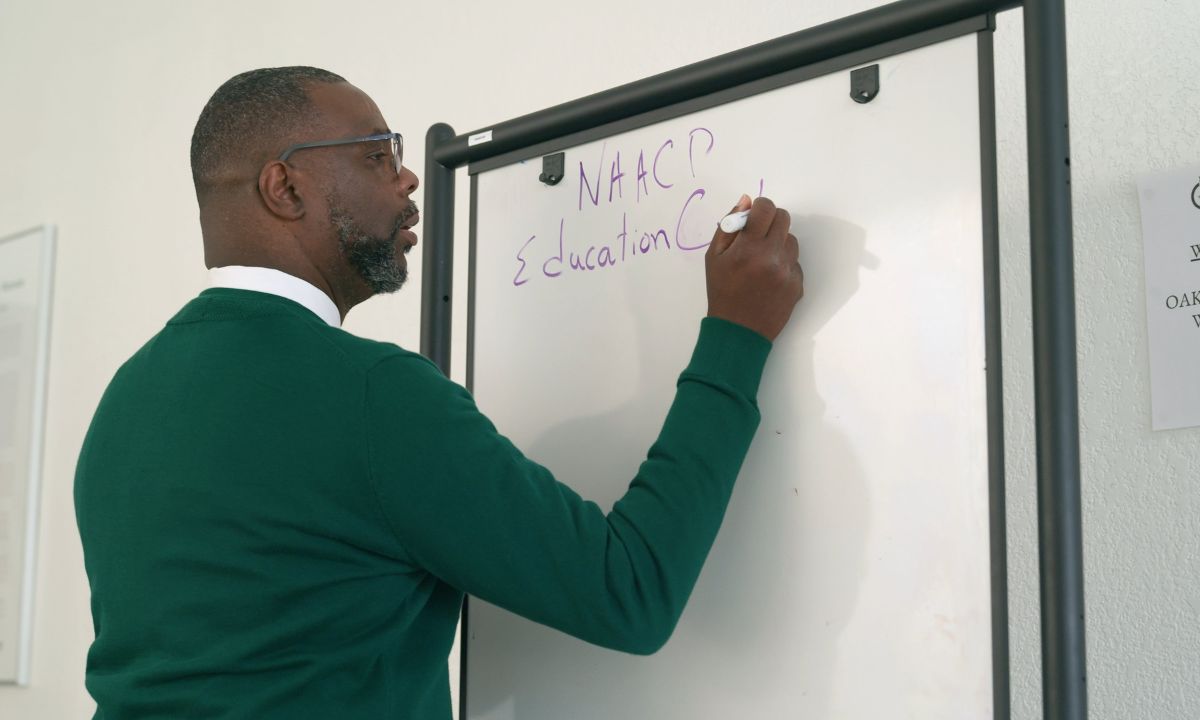

The campaign began with a Jan. 17 screening of a film it’s named after, called Right to Read. The documentary follows Oakland-based NAACP activist Kareem Weaver, who filed a petition with the school district demanding change because of low reading scores. LeVar Burton, who hosted the television series Reading Rainbow for 23 years, was an executive producer.

The St. Louis NAACP will soon launch a listening tour to get feedback from superintendents, teachers, parents and nonprofits about how to improve student reading.

Education chairman Ian Buchanan said the chapter plans on partnering with local school districts in the coming months in order to reach that goal.

“This extreme crisis in literacy has impacted Black and brown students more acutely than others. And so, given this reality, we want to take a stand and put a line in the sand to say, ‘Hey, we know that we can do better and we know that we can do better collectively,’ ” Buchanan said. “So this is a call to action for all school districts to recalibrate, to recommit and to be more deeply committed to improving literacy scores.”

With more than 16,500 students, St. Louis Public Schools has had bleak reading scores for the past 10 years. But the disparity between Black and white students has been skyrocketing. In 2013, 19% of Black third graders scored as proficient in reading on standardized tests, versus 43% of their white classmates. But by last year, that disparity had increased by 23 points, to 14% versus 61%.

Research shows that students with low literacy rates have a higher risk of dropping out of high school, entering poverty or becoming involved in the criminal justice system.

“You have a young African American, male or female, who may be a parent, who dropped out of high school — their literacy level is extremely poor and there’s no way that didn’t create this burden, blocking (them) from opportunities and being successful in the long haul,” chapter president Adolphus Pruitt said. “So we thought of economic empowerment and literacy as being one in the same.”

Missouri’s reading proficiency scores have also declined over the last decade. For third graders, scores dropped from 48% in 2013 to 42% in 2023. These results prompted a new literacy law to be passed last year, requiring schools to create success plans for students with reading deficiencies.

The law is part of a comprehensive plan, Missouri Read, Lead, Exceed, that aims to increase evidence-based literacy instruction, part of the science of reading.

Buchanan said Right to Read’s initial goal is to close the literacy gap between Black students and the state average. There’s a focus on third grade because research has found that 1 in 6 children who aren’t reading proficiently by then won’t graduate from high school on time.

Even school districts in higher-income communities have wide gaps between Black student reading proficiency and the state average.

For example, just 9% of students in the Kirkwood School District qualify for free or reduced-price lunch, but only 33% of Black students were reading proficiently at the end of third grade in 2023, according to state data.

“The data tells us that all we really need to do in order to first eliminate the gap between Black students and the state average is to move, on average, one or two students per third grade, per school, per year to proficiency,” Buchanan said.

Other local nonprofits that are committed to boosting student literacy are partnering with Right to Read this year. For example, parent advocacy group Bridge 2 Hope St. Louis has been managing a literacy campaign called Bridge 2 Freedom since last summer.

The campaign distributes books, hosts essay writing contests and is part of a free parent academy that teaches families to become better advocates for their children and connects them to services and academic resources.

“A lot of our parents who come into the program didn’t know that they had rights. They didn’t know the right questions to ask,” said CEO Krystal Barnett. “They didn’t know that they could ask for their kids’ reading scores. They didn’t even know that a report card was not an accurate depiction of what a child can do in school.” The academy, she said, “puts people in the position to make different decisions and to get better results.”

More than 300 parents have participated in Bridge 2 Hope’s parent academy. Other organizations around the U.S. have pursued similar paths of making parents education advocates, such as Oakland REACH, which worked with its local NAACP branch to push the Oakland Unified district to adopt a research-based reading program.

Barnett added, “I think the Right to Read will open the eyes of people about what strong reading instruction can actually do for a child.”

Another St. Louis initiative is training older adults as tutors to help advance student reading proficiency. The Oasis Institute partners seniors with students in kindergarten through third grade who need academic or social emotional support. A 2023 report found that the parent-led tutoring effort produced similar gains in reading for youngsters as instruction from classroom teachers.

Nonprofit Turn the Page STL is also teaming up with Right to Read. The organization was launched in 2020 as a local chapter of the Campaign for Grade Level Reading, a national organization that has more than 300 branches across the U.S.

Founder Lisa Greening said Turn the Page STL is a network of nonprofits with one goal in mind: improving St. Louis students’ reading proficiency.

The organization is especially focusing on the area’s lowest-performing districts, where Greening said Black and brown children still receive an inequitable education.

“We have the resources here in St. Louis. We’re just not connecting with each other,” she said. “I don’t know anything more important than a child being able to read, because that is one of the most critical self-determinants of life.”

Buchanan said pulling together resources across the St. Louis community to help dissolve systemic inequities is essential.

“Literacy is an issue across the board, even with affluent students,” he said. “But one of the things that history tells us is that when white America has the flu or a cold, Black America has pneumonia.”

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)