Oakland Study Finds Parents as Effective as Teachers in Tutoring Young Readers

CRPE’s look at The Oakland REACH called parents ‘untapped pools of talent’ in promoting literacy.

Get stories like this delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

A new report finds that a parent-led tutoring effort in Oakland produced similar gains in reading for young students as instruction from classroom teachers — a nod that could fuel similar efforts in other districts.

“The more the children know you and trust you, the more they’re willing to engage in what you’re trying to teach them,” said Susana Aguilar, one of The Oakland REACH’s “literacy liberators.”

The evaluation, from the Center on Reinventing Public Education at Arizona State University, calls community members “untapped pools of talent” in the effort to improve student achievement.

Oakland Unified’s model, said researcher and lead author Ashley Jochim, also has broader implications for how schools teach basic skills in reading and math. For too long, she said, one teacher has been responsible for modifying lessons to meet the needs of 25 or more students.

“This model is clearly failing students and puts extraordinary demands on educators, especially coming out of the pandemic,” she said. “Oakland’s tutoring model shows what’s possible when we create the conditions needed to individualize instruction based on students’ learning needs.”

‘How far could they go?’

The Oakland REACH mobilized to improve literacy instruction before the pandemic and joined with the local NAACP to push the district to adopt a research-based reading program.

The group criticized the quality of remote learning during COVID. But then it created its own online “hub” to focus on structured reading skills and saw promising results. After five weeks of virtual summer learning, some students gained as much as they would from two months of in-person reading instruction, data showed.

“We saw these big gains. You can’t ignore that,” said Lakisha Young, the organization’s CEO. “We had to ask, ‘What does this look like for a paraprofessional who is appropriately trained, trusted and coached? How far could they go?’ ”

The group expanded to serve students during the school year, and last year, received a significant boost from philanthropist MacKenzie Scott, who donated $3 million to the organization. Its work, and its relationship with the district, has evolved, Young said, from “demanding to building.”

In statement to The 74, a district spokesman said its literacy efforts “have only been amplified and supported by partnering with a dedicated organization such as The Oakland REACH.”

As a bridge between the district and the predominantly Black and Hispanic community it serves, The Oakland REACH played a key role in finding a diverse mix of tutors that included a retired educator, a former security guard and several stay-at-home moms.

“It’s personal to me because my daughter had to go through the process of long-distance learning,” Aguilar said in a video released with the report. “I completely relate to all the challenges that parents had.”

The prospective tutors completed an eight-week fellowship in which FluentSeeds, a nonprofit trainer, taught them how to implement the district’s phonics-based early reading curriculum. But their preparation — the topic of a separate report — was carefully designed to address the challenges facing Black, Hispanic and lower-income job candidates who are juggling work and family life. The sessions included child care, meals, transportation and a $1,675 stipend.

The fellowship also gave tutors space to discuss personal experiences with literacy instruction — their own and their children’s.

“Their personal struggles,” according to the paper, “deepened their sense of commitment to students’ literacy needs.”

In total, The Oakland REACH recruited 46 parents and other community members to tutor small groups of K-2 students who were reading below grade level. In a survey, about a third of the tutors said they felt somewhat or very unprepared to teach young children when they started, but grew more skilled with the help of ongoing coaching from FluentSeeds.

Aguilar now works at Manzanita SEED Elementary School, where her daughter Aliah is in fourth grade. She described the school, which has a mostly low-income Black, Hispanic and Asian student population, as a “melting pot.”

“When you’re serving underprivileged communities,” she said, “kids are more receptive if they see people who look like them.”

Uneven results, ‘budget challenges’

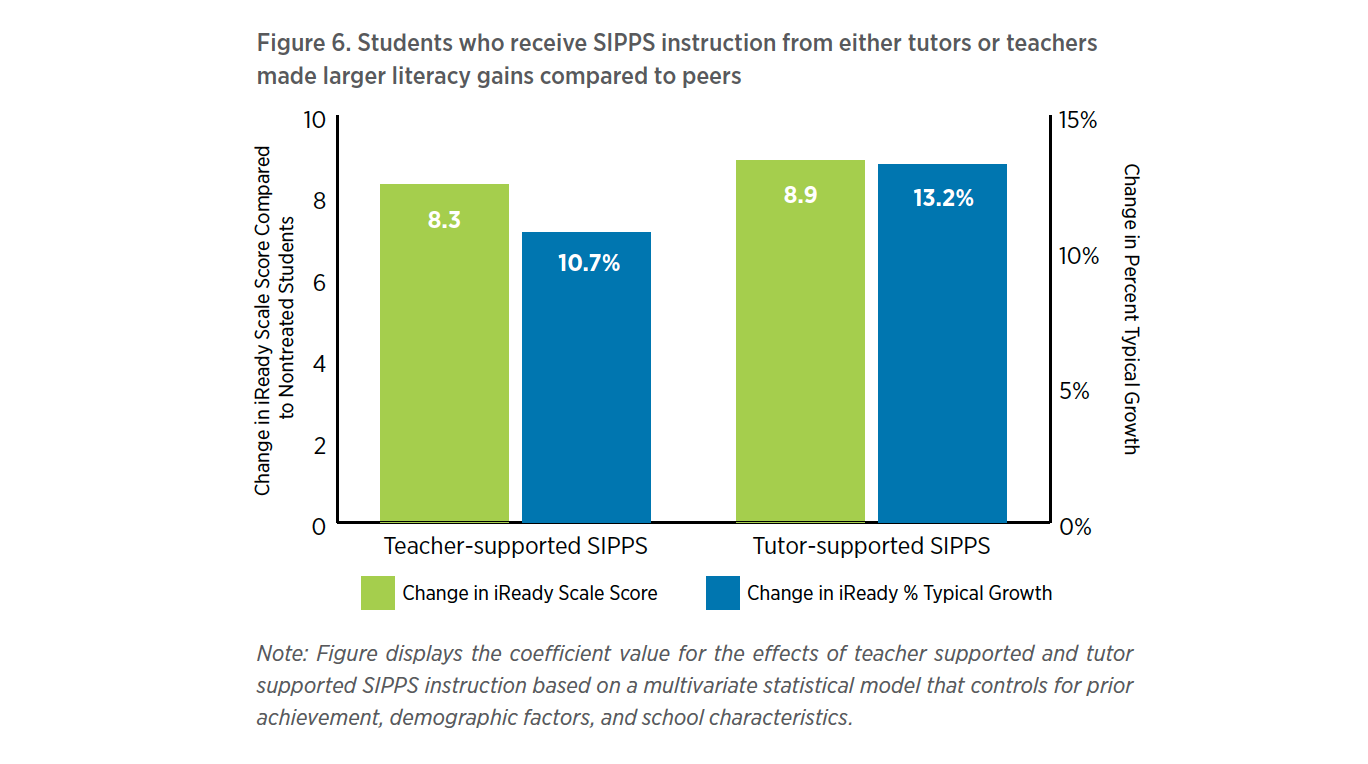

The program has made its greatest impact in kindergarten. From fall 2022 to spring 2023, tutored students gained nearly a full extra year of learning on the widely used iReady assessment, compared to those who did not receive tutoring, according to the report. But there was little to no difference in outcomes between tutored and non-tutored students in first and second grade.

Those results are not unique to Oakland. Another recent study on a virtual early literacy tutoring model called OnYourMark found minimal impact in second grade. The lack of growth could be due to a mismatch between tutoring and testing, said Susanna Loeb, a Stanford University professor who leads a nationwide tutoring research center and conducted the OnYourMark research.

If tutors are focusing on skills that an assessment doesn’t measure, “we won’t see learning gains, even if they have them,” she said.

Overall, however, she described Oakland’s tutoring effort as a “proof point” that shows how well-trained community members with credibility among families “can meaningfully improve student learning.”

But there’s still room for improvement. Many tutors were drawn to the position because they care about Oakland students. But the current $16- to $18-per-hour pay rate is a barrier to recruiting more tutors and keeping them, Jochim wrote.

Aguilar, a single mother, said that while being a tutor is “meaningful work,” it doesn’t pay enough to replace the salary she used to make at her previous human resources job in Silicon Valley. She makes ends meet by delivering groceries for Instacart and recruiting students for a local college.

The district’s “ongoing budget challenges” make the tutoring initiative a “promising, yet still-fragile set of reforms,” Jochim wrote. In March, the board considered cutting the positions, but rejected the plan. The district has relied on federal relief funds to help pay the tutors and is “working out funding for these important positions” once those funds expire next year, a spokesman said.

The recent results should prompt Oakland to stop funding “less effective approaches” to tutoring and invest in what works, Loeb said. “This model is a good example of how community groups can provide these resources.”

Disclosure: Walton Family Foundation, Chan Zuckerberg Initiative and The Charles and Lynn Schusterman Family Philanthropies provide financial support to The Oakland REACH and The 74.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)