South Carolina Voters Will Soon Elect State K-12 Chief — and Decide If They Should Never Do It Again

EDlection2018: From coast to coast, The 74 is profiling a new education-oriented campaign each week. See all our recent profiles, previews, and reactions at The74Million.org/Election (and watch for our Election Night live blog Nov. 6)

Update, Oct. 18: Democrat Israel Romero is withdrawing from the superintendent’s race. He declined to comment on reports of his criminal record and told The Post and Courier that he is withdrawing for health reasons.

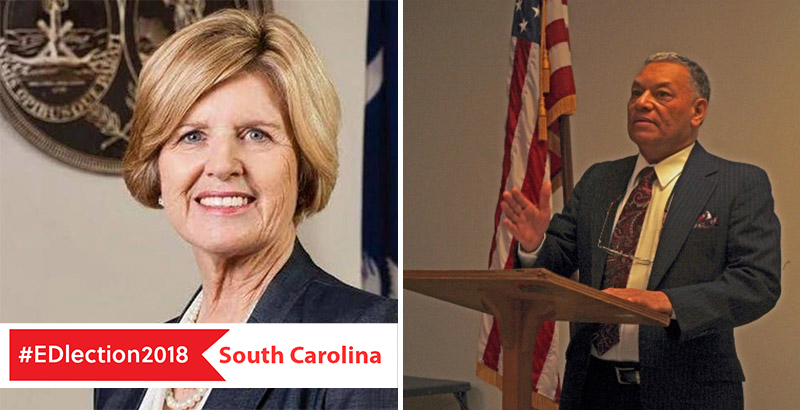

At the same time Molly Spearman is asking South Carolina voters to re-elect her as state superintendent of education, she’s asking them to make it the last time they can do so.

South Carolinians next month will decide whether to amend the state constitution to allow the governor to appoint the state superintendent, putting their state in line with the 37 others where K-12 education leaders are appointed, either by governors or by state boards of education.

The appointed superintendent would have to have an advanced degree and extensive experience in education or business, effective in 2023.

It’s not weird to ask for voters’ support this year at the same time she asks them to back the constitutional change, Spearman said.

“I have run for this office, and I see the difficulty in campaigning statewide and raising funding. I also know that the team effort, with the governor really being held accountable, and him being very much more involved in the policy, would be a good thing for the state of South Carolina,” Spearman, a Republican, told The 74.

Advocates for the change say the main advantage is that having an appointed superintendent puts accountability for student outcomes in the hands of the governor, the official most citizens already believe is in charge of education.

“Education is the most important thing a state does. We believe it’s essential that the governor be responsible for that. When you have a separately elected education superintendent, the governor has no control over education, and when he has no control, he has no responsibility. He doesn’t have to be an advocate for education,” Cindi Ross Scoppe, formerly an editor and columnist at The State, a newspaper in Columbia, told The 74 earlier this year.

Supporters of electing superintendents — in South Carolina, primarily the state’s teachers union — say it’s important to make the superintendent more widely accountable and independent.

Electing the superintendent “allows the office to be directly accountable to the voters, rather than accountable only to a governor. Likewise, the Department of Education is and should remain an independent advocate for the needs of South Carolina public education,” the South Carolina Education Association said in a document outlining its 2016 legislative priorities. It also cited success in blocking a similar bill in 2015.

Spearman’s Democratic opponent, education policy professor Israel Romero, opposes the change, saying it would make it harder to close the achievement gap.

“What they are trying to do is have control. … The superintendent has to be independent, not somebody who is being given instructions by the governor,” he told The State.

South Carolina media reported Oct. 16 that Romero is not eligible to hold the office because of a felony conviction.

He was convicted of unauthorized practice of law in October 2008 and was incarcerated as late as April 2009, the Anderson Independent Mail reported, “for presenting himself as an attorney while trying to represent someone on an immigration case.” The state constitution prohibits felons from running for office within 15 years of serving prison time, according to the paper.

Election officials told the paper that state parties can work with candidates to voluntarily withdraw from the race, though if that happens late in the election process, the candidate’s name might remain on the ballot but not in the eventual reporting of results. Romero did not respond to the paper’s requests for comments.

A review of data by The 74 found little quantifiable difference between states with appointed superintendents and those with elected ones. Those with appointed superintendents have better high school graduation rates and spend more per student, while those with elected superintendents have smaller gaps in high school graduation rates between white students and students of color, and have slightly better test scores, as judged by average results on the 2017 NAEP, the usual national benchmark.

There are numerous drawbacks to electing state chiefs, advocates say.

First, the pool of people who are willing and able to raise funds and campaign for statewide office is not necessarily the same pool of people who would be good education leaders.

And it’s hardly a high-profile job.

Tony Bennett, who was elected to the job in Indiana and appointed in Florida, said a hotel front desk clerk recognized him the day after his 2008 election, from a TV interview playing in the lobby. The clerk had voted for him, she said, because she recognized the name — that of the famous singer, not the superintendent.

Bennett said his time in Indiana was the ideal setup: He and then-Gov. Mitch Daniels had no differences in education policy positions and priorities.

“In Indiana, I had the best of both worlds, because I was a separately elected state chief who was in lockstep with the governor on policy issues. Therefore, I got to use the governor’s political capital, because I was using them on a policy agenda that was jointly held by both of us,” he said.

But Bennett, too, firmly believes superintendents should be appointed. “That way, everybody’s working off the same sheet of music,” he said.

There are several recent examples of elected superintendents and governors playing different tunes, another argument for appointed superintendents, supporters say.

In Wisconsin, Superintendent Tony Evers, officially nonpartisan, and Republican Gov. Scott Walker have led the state since 2011. Even before Evers decided to run as a Democrat for governor against Walker (a race in which polls have found Evers a few points ahead), the two had disputes.

Walker refused to sign the state’s Every Student Succeeds Act plan, drafted by Evers, writing that it “does little to challenge the status quo to the benefit of Wisconsin’s students.” (ESSA required state education departments to give governors a month to review plans, but their signatures were not required; the federal Education Department approved Wisconsin’s plan in January.)

In Indiana, then-Gov. Mike Pence, a Republican, and Superintendent Glenda Ritz, a Democrat, often clashed before she lost her re-election bid in 2016. Lawmakers this year voted to make the job an appointed position beginning in 2025; incumbent superintendent Jennifer McCormick recently announced she won’t run for re-election in 2020.

This year could set up a similar clash in California, between reform supporter Marshall Tuck as superintendent and skeptic Gavin Newsom as governor.

Electing state superintendents also adds to voters’ burden at the ballot box.

In South Carolina, that’s already substantial: Beyond the usual positions like governor and attorney general, Palmetto State voters cast ballots for secretary of state, comptroller, treasurer, and agriculture commissioner. This is the first year they won’t vote for adjutant general, the leader of the state’s national guard.

Despite the high-profile support, the outcome of the South Carolina ballot initiative is far from certain.

It’s a wonky issue in a state where, after a runoff in the Republican gubernatorial primary, there are few close statewide or congressional races of the type that have attracted public and media attention elsewhere.

Advocates have tried to change the superintendent’s status for decades, and the bill required to put the question in front of voters squeaked through the state Senate just before the legislature adjourned for the year.

Also, it seems, voters are hesitant. It’s hard to make the case for less democracy, after all. In 2014, more than 43 percent of voters opposed changing the state constitution to allow the governor to appoint the adjutant general.

Scoppe, the former editor at The State, is concerned that this may be the only chance to change the structure.

“The legislature has been so resistant to putting this on the ballot that if we lose, we’re not going to get another opportunity,” she said.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)