Beyond ‘College for All’: With Success Eluding More University Hopefuls, High Schools Are Pivoting to Prepare Grads for Prosperity Without a Bachelor’s Degree

Correction appended Nov. 26

Public education in the United States changes very slowly — except when it changes fast.

As recently as the mid-1990s, less than one-fifth of women in this country and one-quarter of men held four-year degrees.

Gains in artificial intelligence, computing power, and robotics over the next decade enabled industry to automate tasks in middle-skill and manufacturing jobs that for generations had employed workers with less than four-year degrees, while radically boosting the demand for high levels of education.

In his first address to Congress, three months after the 2008 election, President Barack Obama urged “every American” to pursue education beyond high school for at least one year. “This can be community college or a four-year school, vocational training or an apprenticeship,” he said.

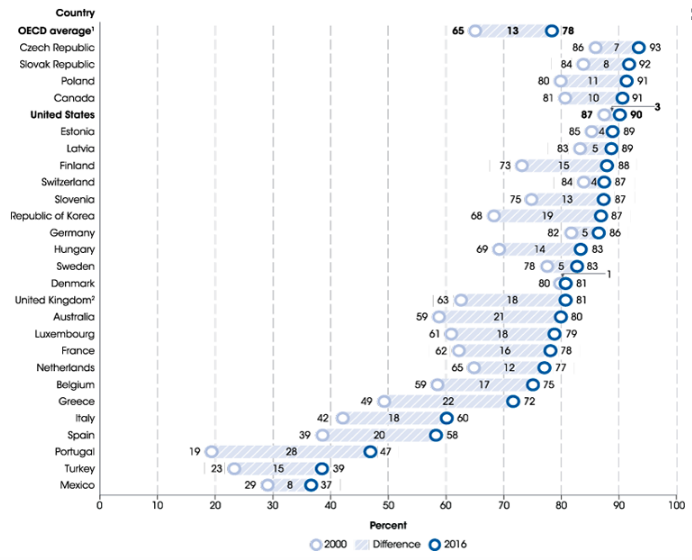

He pledged to provide “the support necessary to allow for all young Americans to complete college” and vowed that the U.S. would have the world’s highest proportion of college graduates by 2020.

Percentage of the population 25 to 64 years old with any postsecondary degree

The goal was unrealistic — while near the top, the U.S. has grown less quickly than high achievers such as Canada, Korea, and Japan — but educators and advocates were cheered. Civil rights groups, who chafed at the tracking of students of color into dead-end vocational programs, and reformers who backed tougher school accountability all believed that aiming to send every student to a four-year college should be a core mission of public schools.

But Obama’s remarks toggled between college and career, implying that higher education, especially four-year schools, were not the optimal destination for all high school graduates. Ruinous college completion rates and the student debt crisis attested to the folly of the “college for all” approach, youth advocates argued. In 2009, just 30.6 percent of Americans had a bachelor’s degree or higher.

The number climbed to 35.7 percent by 2017, but the rate for black (22.8 percent) and Hispanic Americans (18.5 percent) lagged considerably.

“Given these dismal attainment numbers, a narrowly defined ‘college for all’ goal — one that does not include a much stronger focus on career-oriented programs that lead to occupational credentials — seems doomed to fail,” wrote the authors of an influential 2011 report, Pathways to Prosperity, which argued that schools need to design “a more finely articulated pathways system” that gives students exposure to both work and college while still in high school.

The cachet of a bachelor’s degree continues to shape K-12 policy and practice — even in schools that do little to prepare students — informing the push for higher standards and more challenging curriculum.

The mantra of student preparation since No Child Left Behind, the former reauthorization of the K-12 federal education law, has been “college or career readiness” — with technical education overmatched in trying to shoulder the latter, advocates say. But workforce pressures over the past decade have reframed training programs as a prelude to a degree rather than an alternative. An emerging “college and career readiness” approach, encompassing both vocational training and traditional academics, seeks to prepare students for destinations that align with their interests, whether through higher education or work.

Few traditional models help calibrate between college and career as a goal for students, and preparation focused on non-educational outcomes risks lowering expectations, possibly stratifying poor students of color even further. Carried forward by technological and economic change, the task of preparedness has become a staging ground for resolving overlapping but distinct claims about the modern role of schools.

“We take a great risk by putting the kind of emphasis we do on college as the goal,” said Harry Brighouse, a philosopher of education at the University of Wisconsin. “I know people will say we want ‘career and college readiness’ and not just ‘college,’ but I don’t think it translates that way to a student in high school.”

College goals boosted by NCLB

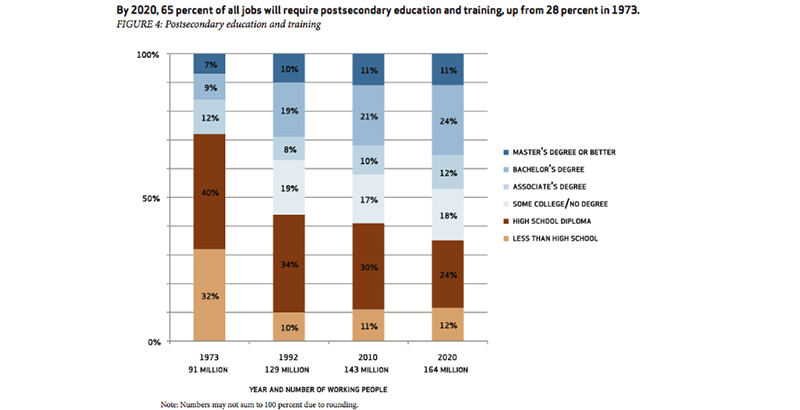

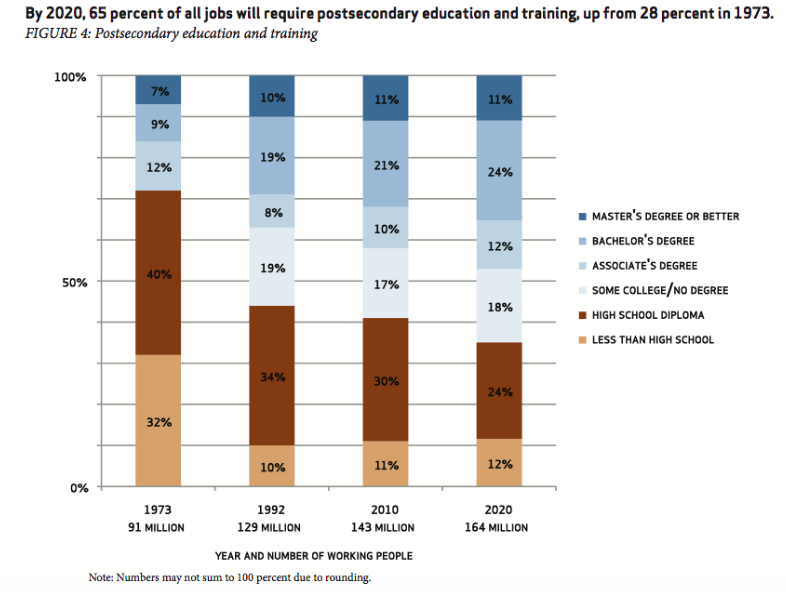

The proposition that all American public school students should attend college suggested itself only recently as part of a massive shift in the late 20th and early 21st centuries in the skills and credentials a good job had come to require.

“The short history is that is up until 1983 in the United States, up until after the 1980-1981 recession, about 70 percent of jobs required high school or less,” said Anthony Carnevale, director of the Center on Education and the Workforce at Georgetown University.

Explosive technological change flipped that ratio by the 1990s, Carnevale said. The nation’s school system began to adopt new systems of skills training and career preparation. No Child Left Behind, signed into law by President George W. Bush in 2002, was in part an effort to boost college credentialing in response to concerns that the U.S. had fallen behind internationally.

Its Woebegonian promise to bring every child in the country to grade level by 2014 implicitly signaled that more students would be prepared to go on to higher education. (When the deadline came, the highest scorers were fourth-graders in math, 42 percent of whom were proficient.) The more difficult Common Core standards later adopted by most states began preparing students in kindergarten for postgraduate success.

“The Common Core is the real first step in articulating what’s needed in preparing for college,” said Jeff Strohl, director of research at the Center on Education and the Workforce. “The language that they use is directly out of [the Department of Labor’s job definition database]. It parallels the emphasis [in the database] on critical skills and client interaction.”

Strohl said the language reflects a common challenge. “In a way, they are addressing the same pressure about work readiness that colleges are facing: What are you doing with curriculum that is preparing students for non-routine, on-demand work?”

While college is the default for many affluent students, the college-for-all message appears to have permeated schools whose students in an earlier era would not have been expected to continue their academic career.

Washington Heights Expeditionary Learning School, located in a heavily Hispanic, working-class neighborhood in New York City, has become known for a celebratory parade of seniors on the way to mail their college applications each fall. Many are the first in the families to apply.

The city’s education department has incorporated rituals like these into a full curriculum, announcing in September that 471 high schools — out of approximately 500 —would participate in a week-long college planning event.

Debating the value of a bachelor’s degree

As automation has replaced middle-skill jobs — those that require more than a diploma but less than a bachelor’s degree — it has pushed wages up for higher-skill jobs. A four-year degree has become the entry fee to the top half of the labor force — the new high school diploma, columnist Catherine Rampell suggested.

“With college attendance more routine today than it was in the past, degrees are becoming a common, if blunt, tool for screening job applicants … ,” she wrote. “Bachelor’s degrees are probably seen less as a gold star for those who have them than as a red flag for those who don’t.”

Of 11.6 million new jobs created between 2010 and 2016, 11.5 million demanded at least some college and 8.4 million required a B.A. or more, according to Georgetown’s Center on Education and the Workforce.

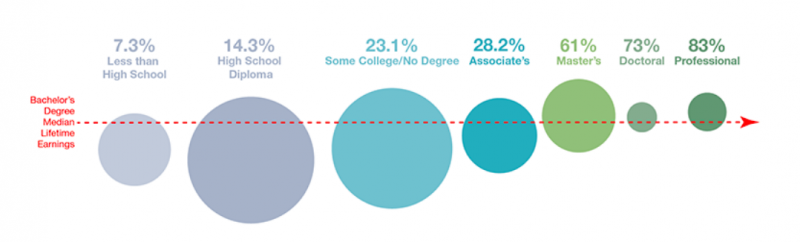

The center calculated that a bachelor’s degree is currently worth $1 million more in lifetime wages than a high school diploma.

It’s not surprising, then, that most high school students say they want to earn a four-year degree. A U.S. Department of Education survey found that 74.3 percent said they wanted to earn a bachelor’s degree or higher. The proportion was consistent across students of different racial and ethnic groups, but lower for those from families in the bottom fifth of income, at 64 percent, compared with the top fifth, at 85.2 percent.

Students were not as optimistic when asked how much education they expected to complete. The portion expecting to earn a bachelor’s degree was 59.4 percent. Among Hispanic students, 71.9 percent said they wanted to earn a four-year degree, but only 50.5 percent said they expected to. Among those in the lowest fifth of income, 44.9 percent said they expected to earn a bachelor’s — 20 points lower than the percentage saying they hoped to.

The evidence suggests that most of the high school students taking part in New York City’s college application event will fail to earn a degree, however. Even at the Washington Heights high school, a pioneer in the extent of its focus on college, less than half graduated last year having met standards for incoming freshmen at the City University of New York, education department records show. Many would have been assigned to redo high school work in remedial classes, which they must pay for but which don’t earn them any college credit, drastically reducing the likelihood that they will graduate.

The luster of college degrees may also obscure the fact that their value varies substantially depending on the area of study. The difference in lifetime wages between a major in a STEM field and a major in early childhood education was calculated by Georgetown to be $3.4 million. And many jobs that demand less than a four-year degree pay more than those that require one.

“Thirty percent of associate’s degrees make more than the average bachelor’s degree,” said Carnevale. “If I get a two-year degree in engineering, I’ll make more than anyone who majored in the humanities [or] education. It ends up being a male-female distinction.”

“It’s also true that a one-year certificate will make more than people who majored in psychology, education, and others in non-business, non-STEM fields,” he said.

In some places, local employers have taken on guidance and training tasks schools are unable to provide. In Louisiana, said Missy Sparks, a human resources executive with Ochsner Health System, the state’s largest employer, most students are not aware of the “tremendous breadth” of health care jobs, in part because underfunded community colleges are unable to keep up with changes in the industry.

“I look at at openings in my organization and I need a pipeline of qualified people more quickly than we’re getting,” Sparks said. Ochsner provides internships to high school students that expose them to health care professions requiring different levels of postgraduate study.

“If they finish high school, this is where they need to make a decision. ‘Do I want an associate’s degree, bachelor’s degree, or license certification, or certificate?’ said Sparks. “We try to bring students in as early as possible [so they can make informed choices].”

Socialized into going to college

A de facto alliance in support of college-for-all between progressives associated with desegregation and centrists associated with charter schools emerged in reaction to decades of racist tracking, which institutionalized negligence toward children of color.

“I worry that formalizing multiple pathways at an early age will reinforce stratification,” wrote Richard Kahlenberg, now a senior fellow at The Century Foundation, in a 2011 blog post. “If we had a well-oiled machinery of meritocracy, which identified talent and drive with great accuracy, divvying up students into different paths in high school might be highly efficient. But there are profound inequalities of opportunity at the K-12 level.”

Although schooling is sometimes looked at as an equalizer of environmental differences, Harvard researcher Raj Chetty and his team have found that “black and white boys have very different outcomes even if they grow up in two-parent families with comparable incomes, education, and wealth, live on the same city block, and attend the same school.”

Kahlenberg, who writes extensively about poverty and schools, told The 74 that his concerns haven’t abated over the past seven years, but he suggested the nation’s rancorous politics made it important not to let attitudes about education worsen broader resentments.

“As a political matter, in the age of Trump, I think progressives need to be extremely careful in promoting policies that are seen as denigrating those who complete their education in high school,” he said. “With our democratic institutions under stress, I think the politics of college-for-all have to be managed very carefully.”

Robert Schwartz, an emeritus professor at Harvard University who co-authored the Pathways to Prosperity report that promoted multiple tracks, argues for a cultural shift in the way success after high school is defined.

“Ask a kid, ‘Why are you going to college?’ It’s just the expectation. You’ve been socialized into it,” he said. “College is the destination itself. It’s not college for what purpose, it’s college for itself.”

Schwartz said a degree without successful work experience “isn’t worth that much anymore.”

But college remains “our North Star” at the KIPP charter network, said Richard Buery, KIPP’s chief of policy and public affairs.

The network, which operates more than 220 schools educating nearly 100,000 students across the country, has a reputation for closely supporting students as they select and attend colleges. Seventy-eight percent of students who complete 8th grade at KIPP go onto college, and 45 percent graduate within six years, a rate that easily exceeds the national average, especially given the network’s traditionally low-income student population.

“That’s high unless you’re one of the 55 percent of students” who don’t graduate, he said.

Buery acknowledged that KIPP had also begun to build better supports for students moving directly into careers, including closer analysis of labor markets in cities where the schools are located.

“I feel like 10 years ago, if a KIPP student didn’t have a college plan, KIPP didn’t have an answer for them. We might love and support you, but we didn’t have a plan,” he said.

“We are on a journey like everybody else.”

Correction: Seventy-eight percent of students who complete 8th grade at KIPP go onto college, and 45 percent graduate within six years. Information on the college outcomes for KIPP students was corrected from an earlier version of this story.

Disclosure: The 74’s coverage of the skills gap, the challenges and opportunities of better educating our future workforce, and efforts underway to improve local employment pipelines is underwritten in part by the U.S. Chamber of Commerce Foundation.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)