‘Something Was Missing’: 97% of North Carolina Survey Respondents Never Taught About State’s Grim Eugenics History

Help fund stories like this. Donate now!

Joseph Palko first learned about North Carolina’s troubled history of eugenic sterilizations from school — but not the one he attended.

Down the road from his Central Cabarrus High School stood the abandoned campus of the Stonewall Jackson Manual Training and Industrial School. Old and rundown, but with an elegant brick facade and tall white columns, the school had a “mythology” about it, Palko said. His classmates would sneak onto the grounds, which operated from the early to mid-20th century as a reform school for boys, and would spook each other with stories claiming the buildings were haunted.

His curiosity piqued, Palko turned to the internet for information on the Jackson school. He quickly learned that in 1948, six teenage boys at the facility — some as young as 14 — underwent vasectomies by order of the state’s eugenics board.

“That was really shocking,” Palko told The 74. “It’s scarier than anything anyone said was going on.”

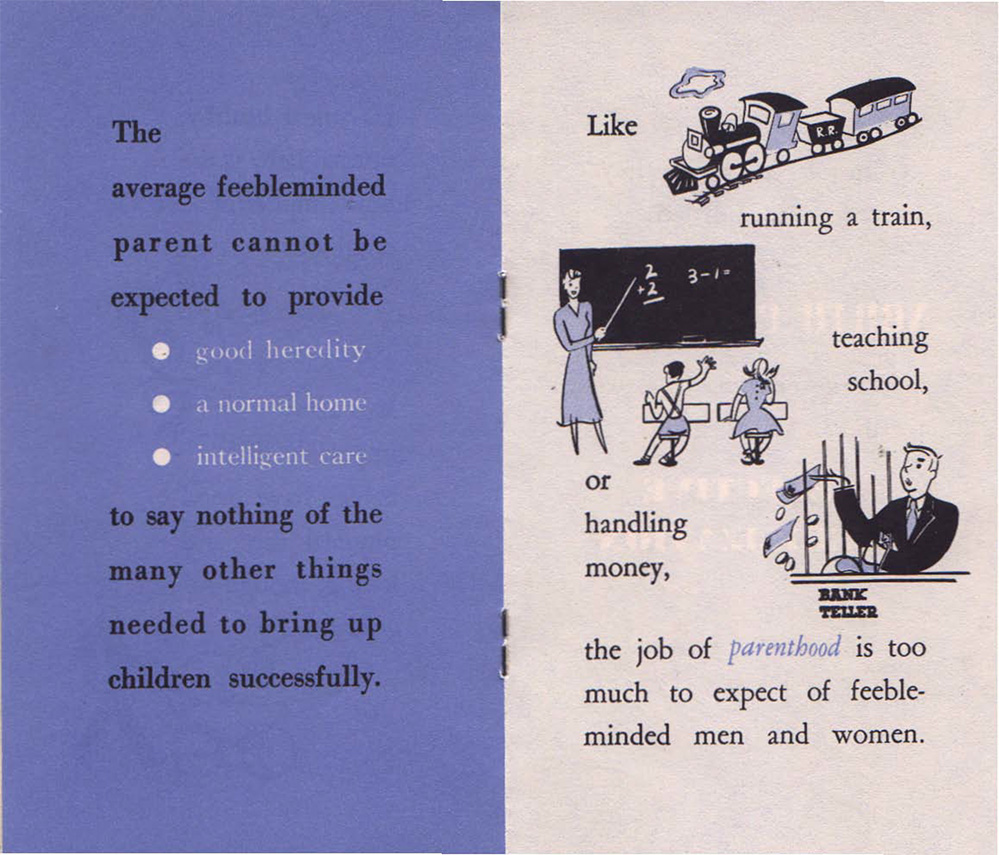

Those six operations, which medically robbed their victims of the ability to have children, were some of the over 7,600 sterilizations carried out by the state of North Carolina between 1929 and 1974 in a campaign to “weed out” disabled and so-called “feebleminded” individuals under the state’s eugenic sterilization law. Over 30 states in the U.S. enacted similar laws, but North Carolina carried out the third-highest number of sterilizations in the nation, after California and Virginia, and in its later years, the program almost exclusively targeted poor Black women.

Palko, who is now a college junior at NC State University, is among the vast majority of North Carolinians who were never taught about their state’s eugenic past in school. Previous reporting from The 74 uncovered that, despite a 2003 state-level directive that information on the state’s eugenics program be included in K-12 curricula, none of the state’s 10 largest districts require that students learn about the tragic episode.

The 74 asked readers of that story to tell us if they knew about North Carolina’s history of forced sterilization and if they had learned about it in school. Responses from 175 individuals help quantify the impact of those untaught lessons:

- Out of 90 respondents who identified as North Carolinians, 87 said that they had never learned about the state’s eugenics past in school, though a few were introduced in college.

- A majority said they had never even heard of the history prior to reading The 74’s reporting.

- Several North Carolina respondents were familiar with the state’s forced sterilization program because their family members were victims of it.

In history class, Palko remembers the national eugenics movement surfacing briefly, but without any information specific to North Carolina. No one prodded further about where sterilizations had happened, and whether they might have taken place in the state they called home.

“I did feel that something was missing in that sense,” said Palko.

Spurred by his curiosity toward the Jackson school sterilizations, the high schooler searched for information on his own.

While most states pulled back from their programs after the atrocities of Nazi Germany laid bare the ethical flaws of eugenics theory, North Carolina accelerated its campaign, he learned, conducting more than 70 percent of all sterilizations after 1945. More than 2,000 sterilization victims were under 18, the youngest being a 10-year-old boy, and procedures often occurred against the will of victims and their parents.

In the latter years of the campaign, 60 percent of those sterilized were Black and 99 percent were female, leading a recent Duke University study to conclude that the state worked to systematically “breed out” Black people through its eugenics program during the late 1950s and ’60s.

“Eugenics control is not exclusive to the Nazis,” Karin Zipf, history professor at East Carolina University, told The 74. Numerous U.S. states, including North Carolina, maintained a mutual exchange of information on eugenics theory and practice with Germany in the years leading up to World War II, said the historian, who authored a book about a reform school for poor, white girls in Eagle Springs, North Carolina: Bad Girls at Samarcand: Sexuality and Sterilization in a Southern Juvenile Reformatory.

As an anti-Critical Race Theory bill advances in the North Carolina legislature, Palko worries that the right-wing outcry against teaching race could further scare teachers away from covering eugenics.

“[It] creates an environment of fear, especially for teachers, of what they can talk about,” he said. In Palko’s own district, the school board passed an anti-CRT resolution that one observer said could incite “witch hunts” for educators covering supposedly controversial topics.

What’s at stake in failing to teach students about this history, said Zipf, is “that we make the mistakes of the past, that we are ignorant of those mistakes.”

For Jonathan Burtnett, who graduated from high school in 1979, learning about North Carolina’s eugenics program as a young person led to meaningful conversations. He grew up in Raleigh and was one of three survey respondents from the state who said they had learned about the sterilization campaign in school.

“The topic made a huge impact on me and it became the topic of multiple dinner conversations at our house with my parents and my siblings,” Burtnett wrote in his survey response.

The 10th of 13 siblings, Burtnett was the only child in his family to receive any instruction on eugenics in school. When his fifth-grade teacher broached the topic in the early 1970s, Burtnett was still learning in a segregated elementary school, nearly 20 years after the landmark Brown v. Board decision.

The eugenics program was still active at that time.

As discussions of eugenics made shockwaves in his nuclear family, Burtnett’s parents told him that his own second cousins who lived in Whiteville were the victims of sterilization against their will, even though they were white and the program affected a greater share of Black families.

Every weekend for more than a month, Burtnett’s parents took him and his siblings to a school for young people with mental disabilities, giving their children a chance to play with the students at the school.

“They wanted us to see that these were the type of children that eugenics was trying to prevent, but they still had value,” Burtnett told The 74. “I think it molded our family the best possible way it could.”

Numerous other survey respondents shared their personal connections to the eugenics program, but chose not to identify themselves:

- “My aunt was sterilized! She was not feebleminded but she was poor and Black and legally blind and so was her husband. My aunt gave birth to their only child and then the state of NC used her being legally blind as a reason to sterilize her so she could not have more kids. Their son was not blind or feebleminded but instead grew up to be a military language expert. He … even worked at the UN.”

- “I learned about this mostly from the news stories during Gov. Easley’s term. That was when I realized this is what happened to my childhood next-door neighbor. She was my father’s age, but had the cognitive abilities of a 12-year-old or younger. I had always been told that she ‘couldn’t’ have children because of ‘an operation.’”

- “My mother had me prematurely at 6 1/2 months in 1965 at age 18 then being 17 while I was conceived,” wrote a respondent from Virginia, where sterilization was also common. “Now I appreciate being here a little more … due to abortion and being my mother [was] sterilized.”

- “I learned about it when working at Wake County [Department of Social Services] in the late ‘70s. One of my supervisors was part of a group who determined who should be sterilized. She still believed it was a good program and shouldn’t be discontinued.”

To Palko, who drives by the Jackson school from time to time when he’s home from college, the old buildings — still standing and now on the National Register of Historic Places — provide him an important reminder about his state’s eugenics past.

“It’s really not distant history,” he said.

Help fund stories like this. Donate now!

;)