Services Denied: Los Angeles Parents, Advocates Slam Weak Rollout of Plan for Students with Disabilities

Families say they’re navigating an uneven & confusing plan 8 months after LAUSD reached deal to compensate students for services lost during pandemic

Get stories like this delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

Correction appended Jan. 10

Every week or so, Los Angeles parent Glenisha Cargin makes a round of phone calls to LAUSD school officials trying to get help for her young son.

Cargin, the mother of a first-grader on the autism spectrum who attends a district school in Westmont, calls the principal. Next she moves on to the school’s special education coordinator, then the local district superintendent.

Cargin also said she “legit (talks) to his teacher every day.”

The boy’s individualized education plan, or IEP — a legal document binding under state and federal federal disability law — entitles him to specific services from LAUSD. (To protect his privacy, Cargin requested her son’s name not be used.) He needs speech therapy. Prone to outbursts and wandering from his desk, he also needs a dedicated classroom aide.

But midway through the 2022-23 school year, the child hasn’t gotten any of these services. During LAUSD’s remote schooling in 2020 and 2021, he wasn’t getting them either.

“There’s regression,” both behavioral and academic, said Cargin. “I don’t feel like he is where he should be.”

Under an April 2022 agreement with the U.S. Department of Education’s Office for Civil Rights, LAUSD must assess whether Cargin’s son and each of the roughly 66,000 district students with disabilities are eligible for “compensatory education” to make up for services many were illegally denied during remote schooling.

Eight months later, parents and advocates say rollout of the plan has been uneven at best, and often confusing with minimal parent outreach. The process can be so opaque that securing even the most basic services requires a lawyer, they said.

“Because parents don’t know what their rights are, no one is holding the district accountable,” said Lisa Mosko Barros, a parent in the district and founder of the advocacy group SpEducational.

“What we have in this district…is a crisis of awareness and information available to parents,” she said. “There should also be an awareness-raising campaign on the part of LAUSD to explain to families what compensatory ed is and why their child might be entitled.”

Advocates across the U.S. hailed the agreement with LAUSD, the country’s second largest district, as a potentially pivotal moment in public schools’ pandemic recovery. A November resolution in Fairfax County, Virginia, the outcome of a similar investigation, brought renewed attention to the issue of regression suffered during the pandemic, especially for students with disabilities.

But LA parents of children with special needs say the agreement simply highlights problems that long precede March 2020.

In a statement, an LAUSD spokesperson said more than 38,000 IEP meetings “with individualized compensatory education determinations” had been completed as of December 1. “The District has also provided information to parents of students with disabilities about the Plan, provided multiple parent and stakeholder outreach meetings and trained thousands of staff members on implementing the Plan.”

But it’s unclear what “determinations” were made — that is, of the 38,000 students whose IEPs were reviewed, how many actually qualified for makeup services.

The decision about who qualifies comes down to an analysis. IEP teams — besides the parent, these include the student’s teacher, a special education coordinator and an assistant principal — must go through records to determine whether a student received the services spelled out in the IEP during the months disrupted by COVID. If not, the district has to offer them.

Under the federal agreement, IEP teams must discuss this analysis thoroughly during their annual meetings with parents, but advocates say they’re skipping over it entirely.

“As a general theme, the district is not bringing up compensatory services,” said Jill Rowland, the education program director at the Alliance for Children’s Rights, which advocates for foster youth.

Rowland and other lawyers on her team representing low-income LA families have observed silence around compensatory education in about 30 IEP meetings this year. When they bring it up, the IEP team members appear at a loss. So parents have to enter informal dispute resolution, a process that takes up to 20 work days, to secure the extra services the child needs.

“Now, that’s all good and great if you have an attorney,” Rowland said. “That is not going to help the majority of kids.”

Cargin got the silent treatment too. At her son’s IEP meeting in August, no one from his school mentioned compensatory education, said Cargin. Four months later, despite Cargin’s constant pressure, her son was still without speech therapy and classroom support.

“The district really is lousy at notifying parents about anything,” she said.

Ariel Harman-Holmes, a parent, attorney and vice chair of the district’s Community Advisory Committee for Special Education, said she suspects parent experience varies “wildly” from school to school.

She considers herself among the lucky ones.

Her son Elijah, a fourth-grader at an LAUSD school in Sherman Oaks, has an IEP for his autism. Handwriting for him is cumbersome, so he avoids it. Although he’s on a track for gifted learners, his ability to form letters on the page is at a kindergarten level.

Harman-Holmes says leadership from the school’s assistant principal in charge of special education is “excellent.”

She and Elijah’s IEP team met multiple times this fall. They reviewed what sort of help he got during remote schooling and discussed whether his difficulties were behavioral, academic or physical.

They ultimately agreed that Elijah did need compensatory occupational therapy.

But the process wasn’t trouble-free. Harman-Holmes had to enter informal dispute resolution because the IEP team members couldn’t grant the services on their own.

“They were like, ‘You have to go to [informal dispute resolution],’” she said. “But at least they were very clear and open about it, and told me how to move forward.”

During a presentation to the Community Advisory Committee for Special Education this fall — one of five the district gave for parent groups — member Kelley Coleman worried that other parents had no idea the plan existed.

“If I wasn’t on the [committee], I would not have any of this information. How is the division of special ed making certain that all families are aware of and understand all of this?”

Other advocates say the outreach sessions don’t come close to cutting it given the district’s size and demographics. Nearly 22% of district families fall below the poverty level, and nearly 12% of families speak English “less than well,” according to U.S. Census Bureau data compiled by the Department of Education.

”The case manager for every child with an IEP should reach out to the family by phone and by email and by a notice in the backpack and say your child might be entitled to compensatory education,” said Mosko Barros. “To my knowledge, that’s not happening.”

Cargin, the mother in Westmont, said she’s been trying to get the district to pay for private services since well before the resolution was announced last April. But she doesn’t blame her son’s teachers or his school’s administrators. “I just think that they get the same answers and the same runaround as I do,” she said.

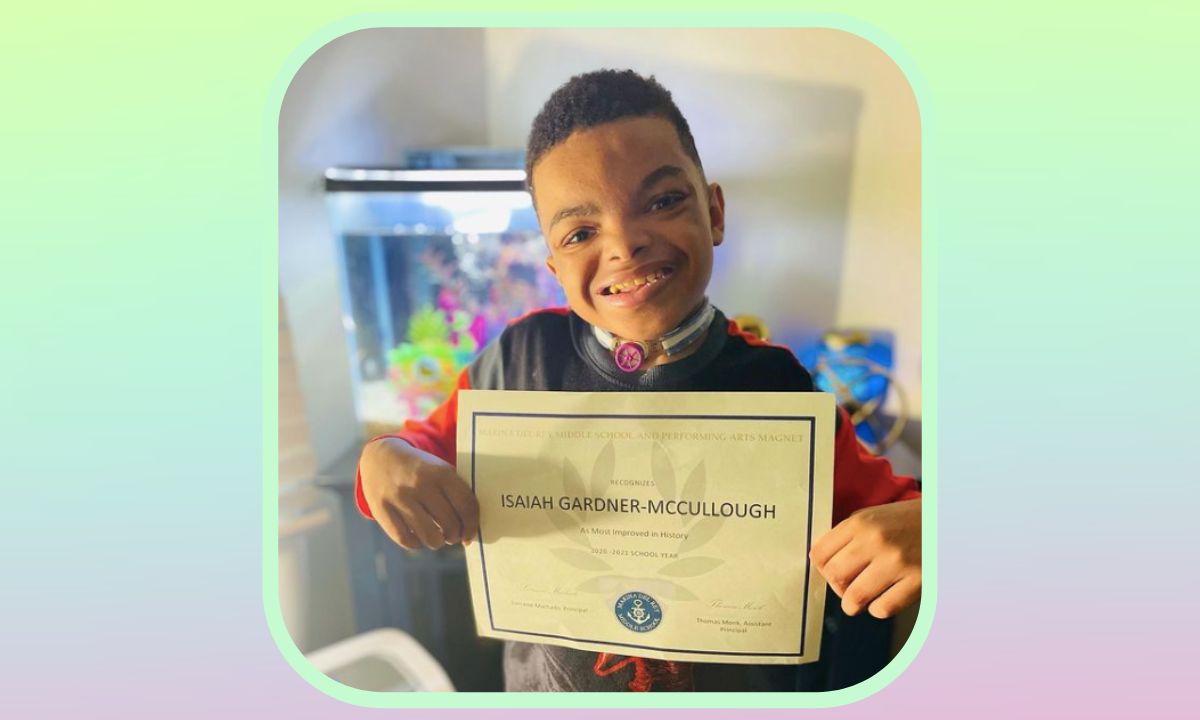

And then there’s the case of Isaiah Gardner.

Isaiah, who’s 14 and medically fragile, requires near-constant attention during the school day. He needs nursing support, speech therapy, and adaptive physical education. He uses a communication device to speak. When the pandemic started, he lost all of these services.

Through a series of administrative proceedings, Isaiah’s mom, Tiffaniy Gardner, secured promises of hundreds of hours of services and the equivalent of thousands of dollars of compensation from the district. But by the time she reached the last settlement agreement in December 2021, she was fed up. The district’s denial of services — including barring Isaiah from entering the classroom once in-person schooling resumed in April 2021 — had humiliated her son.

“To me, it felt like you guys don’t want him here. You don’t value him as a student, you don’t value him as a community member,” said Gardner.

LAUSD would not discuss Gardner’s case or others with The 74.

On April 15, the single mother flew with her three boys to Dallas so Isaiah could attend a public school in the suburb of Mansfield known for its disability services. The transition has been tough for Isaiah, she said. He still talks on the phone regularly with his nurse and teacher from LA Unified.

But Gardner feels she made the right decision. And she wants to remind parents that they have agency during IEP meetings.

“A lot of times people don’t understand that their voice is just as important as everybody else in that room,” she said. “It’s your call to make about your child.”

Correction: Story was changed to correct the spelling of Glenisha Cargin’s name.

More information about LAUSD’s compensatory education plan can be found here: https://achieve.lausd.net/compedplan

Parents can also email Covid-Comp-Ed-Plan@lausd.net or call (213) 241-7696

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)