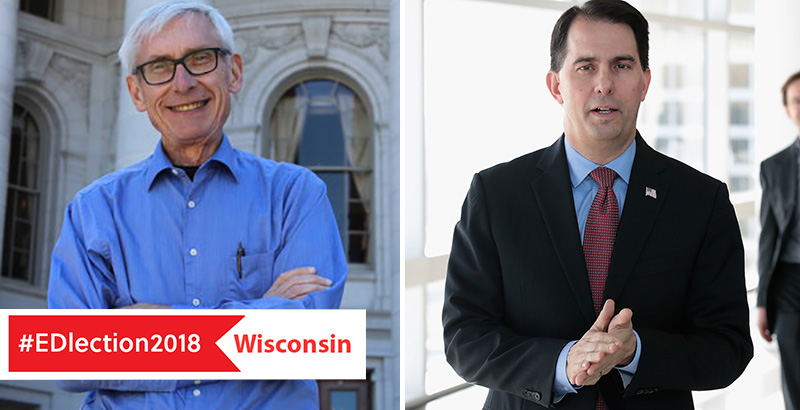

Scott Walker Crushed Wisconsin’s Teachers Union. Can He Win a Third Term Against Its Superintendent of Schools?

Updated 8/15: In the August 14 gubernatorial primary, Tony Evers won the Democratic nomination to face Gov. Scott Walker in November.

Elections in Wisconsin have tended toward the rough-and-tumble in recent years, a reflection of the state’s jagged partisan divide. But even the most campaign-weary voters in Milwaukee and Green Bay must have been surprised by a development in the gubernatorial primary this month, just days before a debate between Democratic candidates. In both cities, billboards appeared asking a striking question: “Why did Tony Evers keep a porn-watching teacher in our schools?”

Evers, Wisconsin’s Democratic superintendent of schools, was elected to his third term in a no-drama contest last spring. And while he holds a decisive lead over his seven primary opponents, none of them were behind the signs. That was the state Republican Party, which has become increasingly convinced that Evers will be the man to contest Gov. Scott Walker’s re-election in November.

If he does, the 2018 elections will unquestionably revolve around the issue of education. Even after a short-lived run for the presidency three years ago, Walker is still best remembered nationally for his 2011 move to strip Wisconsin teachers of their collective bargaining rights. His most prominent foil in Madison is Evers, who has fought against Walker’s efforts to cut property taxes at the expense of school funding — albeit in his own, notoriously soft-spoken, style.

But even as his party’s front-runner, and one of just three Democrats holding statewide office in Wisconsin, education commentators say that Evers’s rollout hasn’t quite set the electorate aflame.

“I suggested to my wife a couple of days ago that if these [Democratic] candidates wanted to attract any serious public attention, they had to be in need of rescue from a three-mile-long cave in Thailand,” Alan Borsuk, a senior fellow at Marquette University Law School and a columnist at the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel, told The 74. Local issues like the travails of Harley-Davidson, or Walker’s troubled bid to bring electronics manufacturer Foxconn to the state, have soaked up press coverage, he said.

If those billboards are any indication, though, the governor’s race won’t remain sleepy for long. And if their attack gains traction, Evers may find himself in need of a rescue after all. (More on this later.)

‘Suddenly, He’s the Education Governor’

Polling of the race shows something remarkable: Four months from Election Day, 61 percent of Wisconsin voters say they don’t know enough about Evers to give a favorable or unfavorable view of him, according to a June survey by Marquette University Law School. He is nonetheless, by far, Gov. Walker’s best-known Democratic challenger, currently leading the field with 25 percent in the same poll (his nearest rivals are tied with 7 percent each).

And yet, even with comparatively little name recognition, Evers (along with three of the seven other Democrats) polls within four points of Walker in a head-to-head matchup. In part, he is helped by the governor’s low ceiling of public support. The proportion of voters who disapprove of Walker’s job performance stands at 47 percent — down a bit since earlier this year, but much higher than any incumbent wants. Simply put, the governor is the most recognizable political brand in Wisconsin — loathed by Democrats as he is loved by Republicans.

The hopelessly polarized view of Walker’s administration is a reflection of the bitter policy disputes he has waged, and won, around health care, voting rights, and abortion. But there is no denying that his 2011 battle with teachers was the fiercest of all.

The reverberations from Act 10 — a package of reforms that eliminated collective bargaining rights from most public employees and forced them to contribute more to their retirement and health care plans — are still being felt around the state. Walker justified the law as a cost-saving measure as Wisconsin emerged from the wreckage of the Great Recession, but many also viewed it as a deliberate blow against teachers unions, a historic foe of the state GOP.

The damage was compounded by the state budget enacted later that year, which slashed $800 million in funding from K-12 schools and passed in the legislature without a single Democratic vote. Those were among the deepest cuts to education in any state, and soon, even some conservative cities and towns began voting to hike their own property taxes to compensate for the loss of aid.

The upside came in the form of lower property taxes, which won goodwill in a historically high-tax state like Wisconsin. But the constant fights over finance and schools have earned Walker the enmity of many.

Pollster Charles Franklin administers the highly regarded Marquette University Law School poll. In an interview with The 74, he noted that Wisconsin voters have favored greater education spending over further tax cuts in recent years. “This is a case where public opinion seems to have turned, to put more priority on public school funding, over these last four years,” he said.

“Where we have seen local referenda to increase school spending, the vast majority have passed; that shows voters willing to tax themselves and support K-12 public schools in their area. You can chalk that up to a better economy; you can also chalk it up to the success Walker has had in holding down property taxes. And you can point to a wide perception of strains on the local school budgets.”

Perhaps that’s why the governor has struck a remarkably different tenor on education in the Trump era. His 2017 budget included a $200-per-pupil spending increase, even more than Evers asked for in his agency’s request. He has regularly boasted in recent months that Wisconsin is now investing “more money into education than ever before.” Marquette’s Borsuk says that Walker has consciously worked to burnish his image in the wake of shifting attitudes, including shooting a campaign ad with a teacher praising his leadership.

“$200 [per pupil] is, in reality, not a huge fortune,” Borsuk said. “But it’s better than schools have done in [Walker’s] prior state budgets. It does soften the issue, and Walker has been talking up education. He’s spent the last year and a half visiting school after school. Suddenly, he’s the education governor.”

Knives Out

At the same time that Walker is softening his image on schools, he’s sharpening his knives for a confrontation with Evers, who many expect to win the Democratic nomination. His most prominent criticism — that the superintendent ignored sexual misconduct among Wisconsin teachers — has been honed for nearly a year.

The same week Evers announced his candidacy for governor last August, the state GOP released ads claiming that he had “allowed a middle school teacher found guilty of spreading pornographic material at school to keep teaching students.”

The charge refers to the case of Andy Harris, a teacher in suburban Madison who was fired in 2010 after administrators in his district found that he had opened and viewed a series of lewd emails on his work computer. After a four-year appeal process that the district spent nearly $1 million fighting, Harris was allowed to return to work on the grounds that his behavior hadn’t involved students. The Walker administration intervened, asking the superintendent’s office to revoke Harris’s teaching license, but Evers shot the request down, saying that he had no such authority under state law.

What followed was a pitched battle over whether Evers was doing everything in his power to terminate employees with a history of moral transgressions. Ultimately, a new law was passed empowering him to pull licenses more easily. But the episode ripened into a potent attack line, one that now haunts him on billboards and the airwaves.

Notably, reporters at the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel have found that the frequency of license revocations by the Department of Public Instruction shot up after the first advertisements were aired last September — raising the question of whether they were politically motivated. In an interview with The 74, Evers dismissed the idea.

“We had one instance where revocation was questionable, and we believed it would have been illegal to revoke a license,” he said. “Every revocation … is unique, and if there were a bunch at one time, that’s no reflection of anything other than the individual cases. It’s just simplistic, and it’s wrong, to say that what we did was in response [to Walker’s attacks].”

Political observers have wondered at times whether the genial Evers could withstand the pressures of a truly tough, Wisconsin-style campaign. Walker is the victor of three previous gubernatorial races — he survived a recall attempt in 2012, after the backlash to Act 10 crested — and his political operation is generally acknowledged to be brutally effective.

Evers’s persona, by contrast, is often described as “laid-back.” One of his primary opponents recently passed on an opportunity to slam him publicly, asking, “What do you say negative about Tony Evers? He’s like my grandfather.”

As if to address this perception, the candidate’s appearances have featured a harder-edged, more profane Tony Evers 2.0, who proclaims himself “goddamn sick and tired” of the Walker administration. (Walker himself took to Twitter to object to his opponent’s coarse language.)

The State of the Unions

Evers’s shot at the governor’s mansion depends to a great degree on whether he can count on the support of school employees. A former classroom teacher himself, Evers should be able to consolidate the support of those still smarting from Act 10 and the education cuts that followed — especially in a year that has seen a wave of teacher activism lead to walkouts and protests around the country. But many doubt that Wisconsin’s educators can be politically mobilized in the same way they were before 2011.

Membership in the Wisconsin Education Association Council, the state’s main teachers union, has fallen from 98,000 to 40,000 over the past seven years. Its roster of employees has been cut by nearly two-thirds, and its annual dues have declined by more than half. Once one of the most powerful forces in Madison, it literally spent nothing on lobbying in 2015-16.

The union has been quiet in the primary thus far, Borsuk says, because “they don’t have any money. I mean, WEAC is a mere shadow of what it once was as far as its political clout. It doesn’t have any money to put up any independent expenses. It’s not going to buy its own ads or anything.”

The union’s diminished capacity is almost entirely the product of Act 10. Thanks to less publicized provisions in the law, all local unions must be recertified via election every year. And if teachers don’t show up or submit a ballot, they count as a vote against certification. Under those circumstances, it is perhaps no surprise that fewer than half of Wisconsin school districts now have certified unions.

Every Democratic candidate for governor has vowed to reverse Act 10 if elected. Evers doesn’t equivocate on this point, though he says that he would be willing to compromise with a Republican legislature by retaining higher employee payments to retirement plans in exchange for a restoration of bargaining rights. Whatever the fiscal needs of the state in the depths of the recession, he adds, the unintended consequences of the law have been damaging to Wisconsin schools.

“Now we’ve spun off into some weird places,” he told The 74. “We have a mass exodus of [teachers] retiring early. We have young people not entering the profession — I know that’s a national issue, but it’s getting worse in Wisconsin. All those things aren’t collective bargaining issues, but they absolutely grew out of Act 10. It has made the lives of Wisconsin teachers more difficult. They feel like they’re operating with a target on their back.”

Indeed, analysis from the left-leaning Center for American Progress shows that teacher retirements in Wisconsin spiked dramatically in the aftermath of Act 10’s passage. Inter-district transfer also increased as teachers who had previously worked under collectively bargained contracts looked for better conditions and pay in other parts of the state. Average length of teacher tenure has ticked downward.

Alec Zimmerman, communications director of the Republican Party of Wisconsin, defended the governor’s record.

“Thanks to Scott Walker’s reforms, Wisconsin is sending more money to our classrooms than ever before — $200 more per student this past school year and $204 more per student in the fall — with the very budget that Tony Evers called ‘pro-kid.’ Evers is a Madison bureaucrat who time and again has failed to stick up for our schools by leaving dangerous teachers in the classroom when families asked for his help.”

If Evers isn’t likely to benefit from a well-funded union effort, he may still enjoy one major advantage: a 2018 political environment that distinctly favors his party. The same tailwinds that have pushed Democrats to unlikely victories in Alabama and Pennsylvania are currently being felt across Wisconsin. In January, a little-known county medical examiner captured a state Senate seat that had been held by Republicans for 17 years. A few months later, Republicans lost in another district that hadn’t chosen a Democrat since the 1970s.

Walker, one of Wisconsin’s keenest observers of political trends, proclaimed the startling results a “wake-up call,” and he later attempted to postpone all further elections until November (a court eventually ruled against him). The possibility exists that, if the blue wave feared by GOP strategists finally rises up from Lake Michigan, Democrats could put Tony Evers in the governor’s mansion and flip one or even both legislative chambers.

More likely, according to Marquette’s Borsuk, would be a split decision, with Democrats having to work around a Republican-held Assembly (the GOP holds a much more secure majority there than in the Senate).

“There probably isn’t going to be an open road to big Democratic reforms even if they do really well in this election,” he said. “There’s not going to be unified government. So at most you’ll have a recipe for gridlock with some need to work some things out like the next state budget. If that happens, with a Democratic governor and a Republican Assembly….”

He trailed off, breaking into a spurt of laughter.

“That would be a very entertaining issue.”

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)