School Reopening, By the Numbers — How 100 Top Districts Are (and Aren’t) Adapting: Parent Waivers, Test Kit Shortages and Learning in Quarantine

Get stories like this delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

This the latest in a series of weekly analyses of COVID-19 policies in 100 large and high-profile school systems, produced by the Center on Reinventing Public Education at the University of Washington, Bothell. You can see the full archive here.

Nearly every school in the country has now reopened for the 2021-22 academic year, but states and districts are still scrambling to ensure students will stay safe and continue learning, with as few disruptions as possible.

We have been tracking reopening efforts in all 50 states and 100 large and urban school districts.

Our nationwide review finds that despite high-profile rancor over mask requirements, debates over them are largely settled. The vast majority (88) districts in our review require them for all students and staff.

Remote learning options have quickly become the norm. Of the districts we track, 94 offer some sort of online learning option to at least some students — up from 79 a month ago, and more than twice the number when we started tracking reopening plans in July.

But while these hot-button issues are starting to cool, our nation’s schools have lots of work to do. This week, we’re focusing on three key issues: COVID testing, vaccine transparency and learning opportunities for students in quarantine.

Testing policies: An underused tool to keep students safe and learning

One intuitive way to keep students safe and learning is to catch the virus before it spreads in schools. That makes testing a critical tool. Nearly a third of the districts we reviewed (31 of 100) require staff to undergo testing for COVID-19, with 8 requiring all staff to get tested regularly even if they are vaccinated.

Newark Public Schools updated a policy requiring weekly testing for all staff. It now applies to unvaccinated adults only.

As for students, the number of districts in our review that require regular COVID testing increased from 9 to 15. Most of these apply only to student athletes.

Testing can also be a valuable way to limit the number of students who have to quarantine. A recent large-scale randomized study out of England shows that when a student has been exposed to COVID, daily testing can be just as effective as a quarantine at keeping the virus from spreading in schools — and without the same disruptions to instruction.

But right now, such “test to stay” policies, which allow students who may have been exposed to the virus to keep coming to school as long as they take daily tests, remain relatively rare on this side of the Atlantic.

Districts that have tried them, such as Boston Public Schools, have run into two critical logistical barriers. First, parents haven’t been quick to sign consent forms necessary to allow the testing. Before the school year started, less than a quarter of students in the district had returned their forms. Second, a surge in demand for tests meant hundreds of Massachusetts schools were slow to receive their test kits.

While these statewide programs aiming to keep kids in school will require more coordination across local services than ever before, the stakes for kids are high. The words of Russell Johnston, Massachusetts’ deputy K-12 education commissioner, explain why addressing these barriers should be a critical priority for state and local policymakers everywhere in the country.

“We only have our students for 180 days out of the school year in most of our schools in the state,” he told the Boston Globe. “And you know, that time matters, every day matters.”

As vaccine mandates stall, few states offer transparency

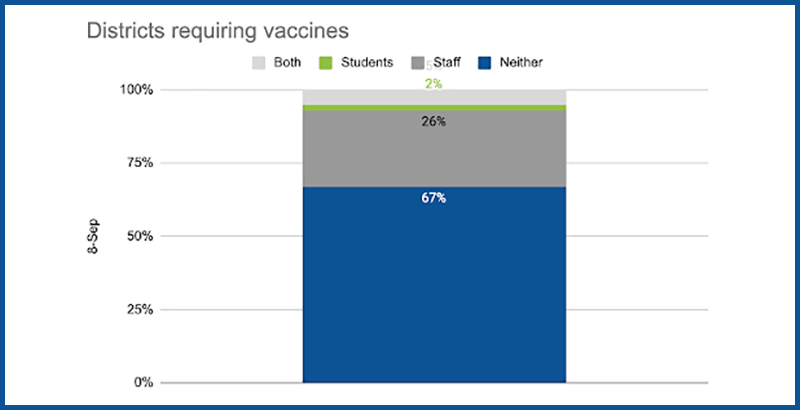

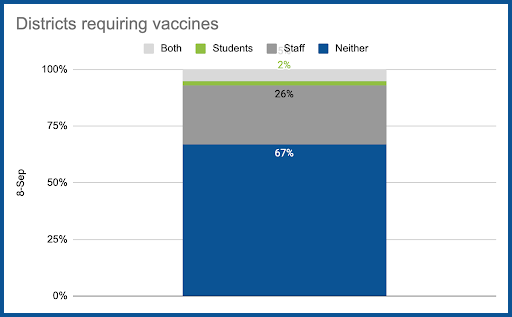

Despite President Joe Biden’s high-profile push last week, vaccine requirements remain in flux for most of the nation’s schools. Nearly a third (31) of the districts we reviewed require all staff to be vaccinated, an addition of just one district (Nevada’s Clark County) since we updated our data last week.

That means in most states and school systems, parents won’t be able to know for sure whether the adults working with their children have taken vaccines. But this information doesn’t have to be secret, and some states have made laudable efforts to increase transparency.

Maine continues to be the only state tracking and reporting teacher vaccination rates, requiring schools to submit this information to the state health department. The Washington Department of Health is moving in the same direction by recommending that schools begin verifying student and staff vaccinations.

The Alabama departments of public health and education collaborated to create a statewide tracker for COVID-19 cases and school reopening status.

In Oregon, Portland Public Schools released a public COVID-19 dashboard this week that reports the number of students in isolation and quarantine by school, as well as staff vaccination coverage across the district.

If states are not going to require all school employees to be vaccinated, these dashboards could at least be updated so parents can see what percentage of adults in their child’s school have received the vaccine. Education leaders can build on reporting practices already established for health care facilities in some states.

Too many districts leave learning to chance for students in quarantine

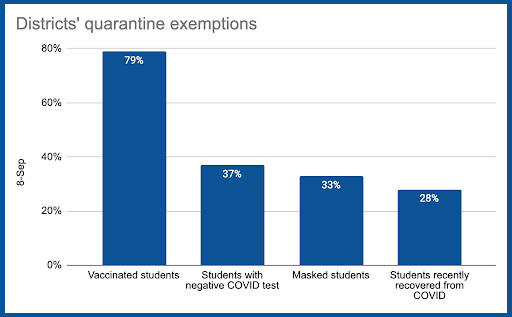

The overwhelming majority of districts in our review (97) now have updated their quarantine policies for the 2021-22 school year.

Most (79) exempt vaccinated students from quarantine, while 28 exempt masked students, 33 exempt students who recently recovered from COVID-19 and 37 shorten quarantines for students who test negative for the virus.

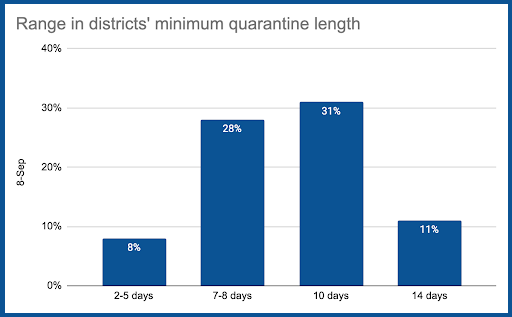

The amount of time a student can miss due to quarantine varies widely. Some districts allow students back as soon as two days after exposure and others require a full 14-day quarantine.

This raises the critical question of how school districts plan to provide instruction to students who still have to stay home because they may have been exposed to the virus.

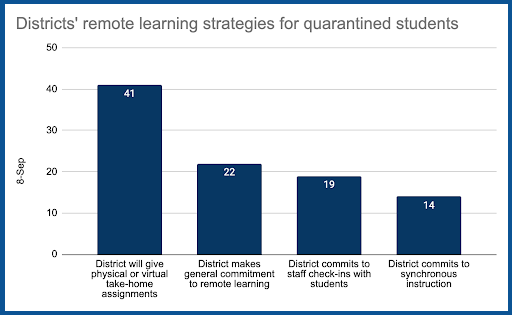

Sixty-six of the districts we reviewed provide some details about what remote learning will look like for students in quarantine, a significant increase from 38 at the beginning of this month.

However, these details rarely show a clear pathway to continuity of learning for quarantined students. The more detailed information provided is about access to work assignments: of the districts that describe learning for students in quarantine, nearly two-thirds (41 of 66) commit to providing take-home assignments or online work for students to complete on their own at home.

But most districts offer no guarantee that students will interact with teachers.

Just 19 (29 percent of those that detail quarantine learning arrangements) will ensure that quarantined students can consult with a teacher or a staff member on assignments while in isolation.

Just 14 (21 percent) commit to providing quarantined students with live, real-time instruction.

Five districts we reviewed — Boulder Valley, Colorado; Houston Independent School District; Kansas City Public Schools; Metro Nashville; and San Diego Unified — will offer their remote learning program or an equivalent to quarantined students.

This means students could face days, or possibly even weeks, with drastically limited instruction after possible exposure to the virus. Students being exposed multiple times could face as much as a month away from school. And these disruptions could fall more heavily on children younger than 12, who are not yet eligible for vaccines and are therefore less likely to be exempt from quarantines.

While it seems nearly impossible to forecast the number of students in quarantine and needing remote options at each school, education leaders should not forget the lessons they learned last year about how to deliver instruction remotely. They should use that know-how to ensure that no students have to miss learning because they need to stay home to keep their peers safe.

Brace for another rocky school year

Overall, our analysis points to a difficult school year ahead.

Parents in most of the country are sending their children to classrooms with no clear understanding of whether the teachers are vaccinated.

Students face widely varying rules about how much school they will have to miss if they are exposed to the virus, and teachers in many places are on their own to figure out how to continue supporting learning for students who have to quarantine.

But we also see some powerful tools — like COVID testing and online learning platforms — that have the potential to help this school year go well.

Making these tools available in every school, and helping schools overcome supply bottlenecks or logistical barriers, should be job one for state policymakers in the coming weeks.

Bree Dusseault is principal at the Center on Reinventing Public Education, supporting its analysis of district and charter responses to COVID-19. She previously served as executive director of Green Dot Public Schools Washington, executive director of pK-12 schools for Seattle Public Schools, a researcher at CRPE, and as a principal and teacher. Christine Pitts is a resident policy fellow at the Center on Reinventing Public Education.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)