Scared of School: Even in States With Protective Laws, LGBTQ Students Are Reporting Attacks from Other Kids — and Teachers

From verbal harassment to physical assaults, a 74 data analysis finds that in both red states and blue, the kids are not all right

By Beth Hawkins | May 24, 2023

Over the last three years, hundreds of bills seeking to strip protections from LGBTQ youth have rolled through statehouses.

In the opening weeks of the 2023 legislative season alone, more than 400 pieces of legislation aimed at LGBTQ people— most of them targeting schools — were introduced throughout the country.

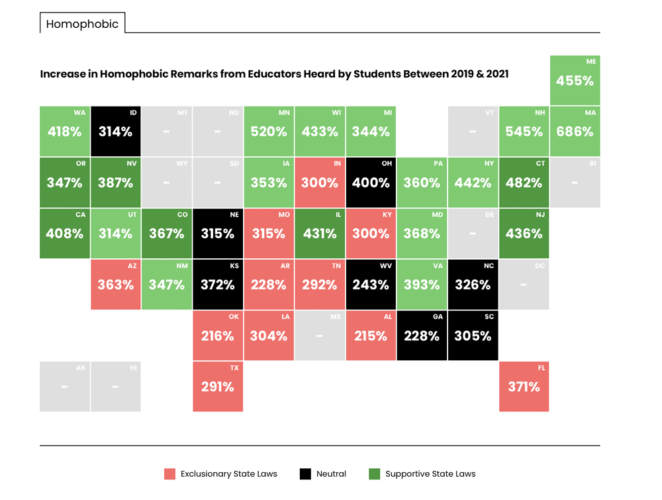

It’s no surprise that queer students in Republican-dominated states where these laws have passed are profoundly impacted. But less visible is the dramatic effect the steady drumbeat of headlines has had on youth in places with even strong anti-discrimination laws. Newly released data from the advocacy groups GLSEN and The Trevor Project show increases in hostility, victimization and discrimination experienced by students in blue states as well as red.

The effects are devastating. Nearly half of LGBTQ 13- to 17-year-olds considered suicide last year, as opposed to some 19% of high school students overall, according to The Trevor Project. Eighteen percent actually attempted it. Seventy percent report anxiety, and 57% experienced depression.

Strong in-school relationships are a well-known protective factor. LGBTQ students who say their teachers care a lot about them are 37% less likely to consider suicide and 43% less likely to be depressed than those who don’t feel cared for, according to The Trevor Project.

Rates of self-harm are much lower among students who feel affirmed in school, and acceptance of LGBTQ students had risen steadily — if unevenly — following legal recognition of same-sex marriage. But the number of youth who see their schools as affirming has fallen dramatically over the last four years.

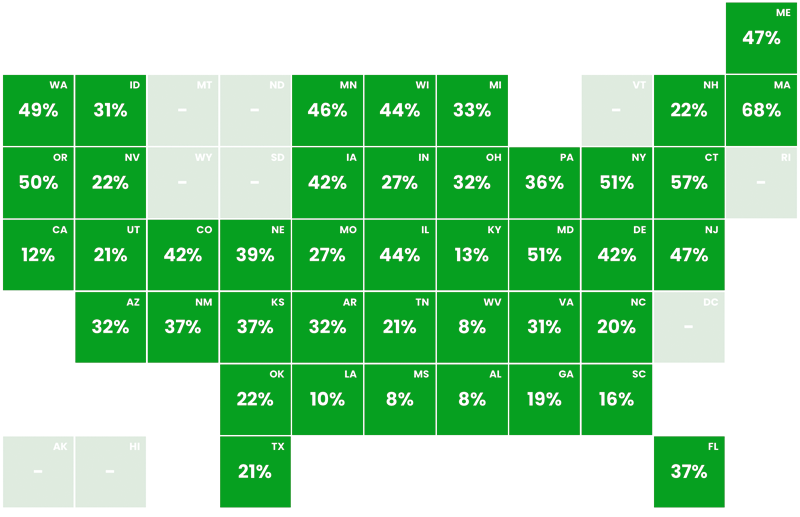

In California — where the first gay couples married in 2008 and schools began teaching LGBTQ history a decade ago — a statewide survey of students found that the number who reported hearing homophobic remarks from adults in school rose from 12% in 2019 to 49% in 2021. That’s an increase of 408%.

In Massachusetts, where same-sex marriage has been recognized for almost 20 years, the number of youth exposed to anti-LGBT remarks is up 686% over the same time frame.

In Minnesota, where queer youth are protected by strong human rights laws, the number is up 520%. In Connecticut, it’s 482%. In New Hampshire, 545%.

The increases are so big in part because acceptance had been on the rise in many places. In red states, the rise in anti-gay and anti-trans speech is smaller — but only because the starting numbers were much higher.

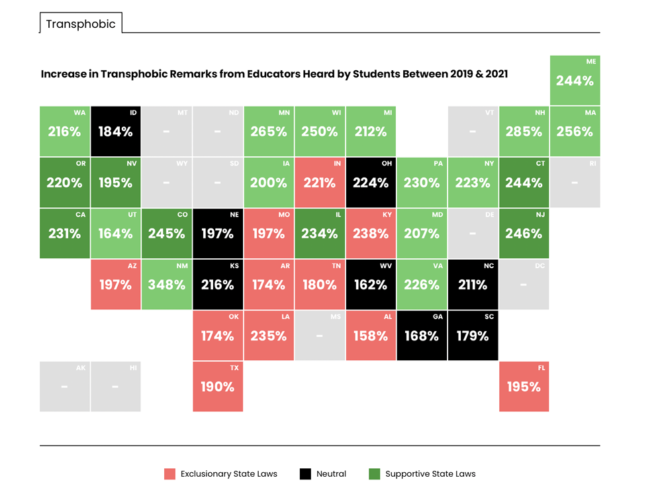

According to the surveys, anti-trans remarks are pervasive. In Louisiana, the number of students who report hearing transphobic remarks from school staff rose 235%, from 34% to 80%. In Texas, the number rose by 190% to 76%. In Missouri, 197% to 73%.

In fact, when reports of hostile speech by peers are added to the rate of problematic adult remarks, there is no state in the nation where fewer than 93% of LGBTQ students reported hearing slurs in school. Nationwide, 83% were harassed, 54% were sexually harassed and more than 12% assaulted.

Kids in the crosshairs

A new data analysis by The 74 shows how this political wedge issue, aimed at a relatively small population of students, is having an outsize effect. The number of youth who identify as something other than cisgender is growing, but it’s still a tiny number of children.

Of the approximately 16 million high school students in the United States, an estimated 1.8 million, or 11.6%, identify as LGBTQ. Just 300,000 are gender-nonconforming.

Ten years after same-sex marriage became widely recognized, a sizeable majority of Americans are comfortable with gay, lesbian and bisexual co-workers and neighbors. Experts say it’s harder to attempt to undo LGBT rights overall than to capitalize on confusion about the experiences of a very small subset of people.

And unlike past campaigns to vilify LGBTQ people, this time, the rhetoric targets kids, not adults. Even though some of the new policies take aim at bathrooms and gymnasiums, the impact spills over to classrooms, hallways and libraries, affecting a much larger number of children.

They are bullied and assaulted; subjected to increasingly negative remarks even from teachers who are supposed to protect them; silenced from raising LGBTQ topics — even talking about their families during class discussions; discouraged from participating in sports or other activities; forbidden from wearing clothing with supportive messages or forming gay-straight alliances or other affirming student clubs; disciplined for identifying as LGBTQ and for wearing clothes deemed “inappropriate” for their gender.

And while queer students often consider their schools safer than even their own homes, too often, they don’t report victimization or discrimination is because they don’t believe the adults will do anything about it.

“They rely on these peer support groups, they rely on sympathetic teachers, counselors, coaches,” says Austin Johnson, a sociology professor at Kenyon College and director of the Campaign for Southern Equality’s Research and Policy Center. “Folks who are meant to be their resources, institutions that are meant to serve them and provide resources to them, actively rejecting them, stigmatizing them — those kinds of things are really damaging.”

Nor can kids simply decide — without repercussions — to stop attending a school that no longer feels safe, he says: “They’re stuck in this environment of hostility and negativity, with no way out.”

Despite the role an affirming school culture plays in protecting LGBTQ students’ mental health, policies prohibiting bullying and discrimination and newer laws requiring positive representations of gender and sexual minorities in classroom materials are poorly implemented. The reasons range from local political pressure to a lack of state and federal oversight. Too often, laws on the books are no match for negative rhetoric and the fear that comes with it.

A 2022 survey by Educators for Excellence found that the number of teachers who say their schools are meeting the needs of their LGBTQ students is falling. The survey showed a sharp decline in educators’ perceptions of how well schools are serving LGBTQ youth, with 41% of respondents in 2020 saying their schools often meet these students’ needs, versus 22% this year. The survey also found that teachers of color and older educators were more likely to approve of instruction on LGBTQ people and topics and to criticize their schools for not doing enough.

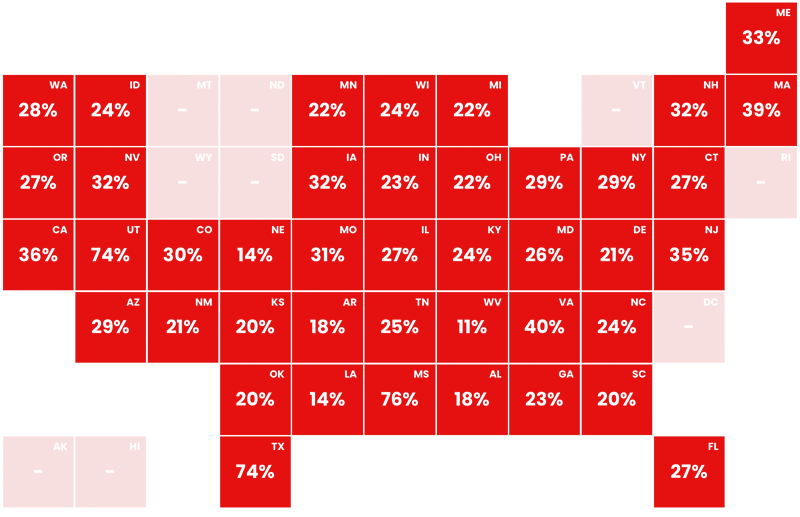

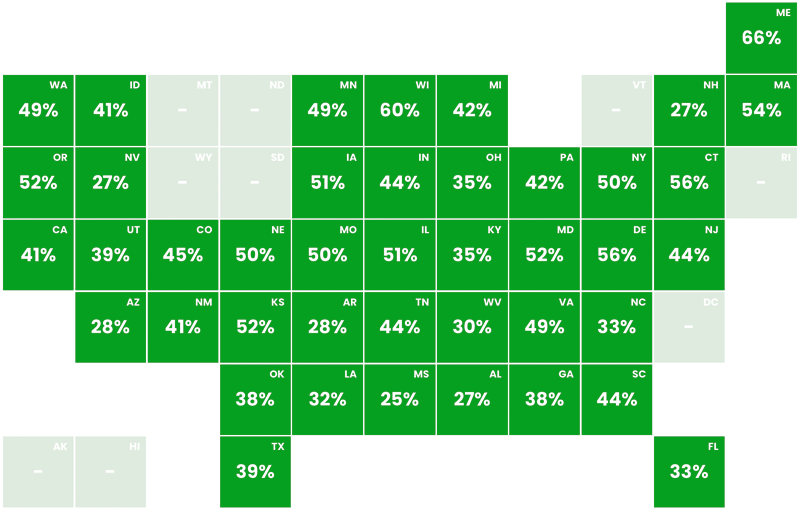

Using data from GLSEN and the Movement Advancement Project, The 74 created a series of interactive maps. The first shows the increase in the number of youth who are the targets of hostile remarks from school staff, with state-by-state breakdown of the percentages and the status of laws and policies affecting LGBTQ students.

Student Experience Map

Increase in Homophobic & Transphobic Remarks from Educators Heard by Students Between 2019 & 2021

Data from the Movement Advancement Project and GLESN’s 2021 National School Climate Survey; downloaded May 18, 2023.

Administered since 1999, GLSEN’s school climate surveys are among a few datasets that include information about LGBTQ youth, although a 2022 Biden administration executive order has directed federal agencies to begin collecting and disseminating information on gender and sexual minorities.

GLSEN’s findings are echoed by data collected by organizations that measure the well-being of all young people, not just LGBTQ students. In Fiscal Year 2022, the U.S Department of Education’s Office for Civil Rights received 633 allegations of discrimination on the basis of sexual orientation and/or gender identity, according to a department spokesperson. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has long found gay, lesbian and bisexual youth at elevated risk of in-school harassment and violence.

In short, researchers say, regardless of whether the so-called culture wars are a coordinated political strategy aimed at voters, they are endangering queer students’ sense of safety even at schools with strong anti-discrimination protections.

‘Don’t Say Gay’ and mental health

Four years ago, for the first time, The Trevor Project, a queer youth suicide prevention group, started asking questions about the political climate and kids’ mental health on its annual survey of LGBTQ youth. Eighty-five percent of those surveyed in 2022 said they pay attention to news stories about LGBTQ rights. A third said their well-being was poor most or all of the time because of the legislation and policies, and 2 in 3 said hearing about potential “Don’t Say Gay” laws make their mental health worse.

Teens in the survey felt the impact regardless of where they live. For example, 86% of respondents in Florida and Texas — both sites of high-profile battles over LGBTQ rights — as well as in progressive Connecticut said the rhetoric has affected their well-being.

Nine in 10 teens in Minnesota and Massachusetts, states with strong civil rights laws, said politics weighs on them — the same number as in Oklahoma, where a number of policies curtailing LGBTQ youth rights have been adopted.

“It’s not enough anymore to say, ‘These laws don’t exist here,’ ” says Johnson. “Even when a law doesn’t exist, the rhetoric around it creates this environment of hostility, fear and confusion.”

According to GLSEN, more than four-fifths of queer teens have experienced in-person harassment or assault and almost as many say they feel unsafe in class and avoid school functions. A fifth have changed schools because of the climate, and a third miss one or more days a month.

Research has long established that the resulting student absenteeism, lack of participation in sports and other school activities, depression and stress are direct causes of lower grade-point averages and graduation rates, dramatically higher discipline rates and other factors that can impact a student’s life trajectory.

A 2023 Trevor Project survey of 28,524 respondents found much higher numbers of LGBTQ students who said they were affirmed at school than at home: 54% vs. 38%. Youth who perceived either setting as supportive were 4 percentage points less likely to attempt suicide.

Queer adults and their supporters often describe the political furor as a backlash against steadily expanding civil rights protections. But the current wave of legislation targets kids — and the schools where many find a supportive community.

“It’s not enough anymore to say, ‘These laws don’t exist here.’ Even when a law doesn’t exist, the rhetoric around it creates this environment of hostility, fear and confusion.”

Austin Johnson, director of the Campaign for Southern Equality’s Research and Policy Center

Proponents cite a number of reasons why the new laws are needed. They seek to shield students from materials they deem inappropriate; to combat supposed “indoctrination” and “grooming” by sexually predatory educators; to stop children from using a new name or pronouns in school without their parents’ consent; and to protect cisgender girls from trans girls in bathrooms and locker rooms, among other reasons.

But LGBTQ-rights advocates counter that the impact of the laws is much broader. To understand how both restrictive and protective policies trickle down — or don’t — to affect LGBTQ students, GLSEN regularly asks queer teens throughout the country about their experiences in school.

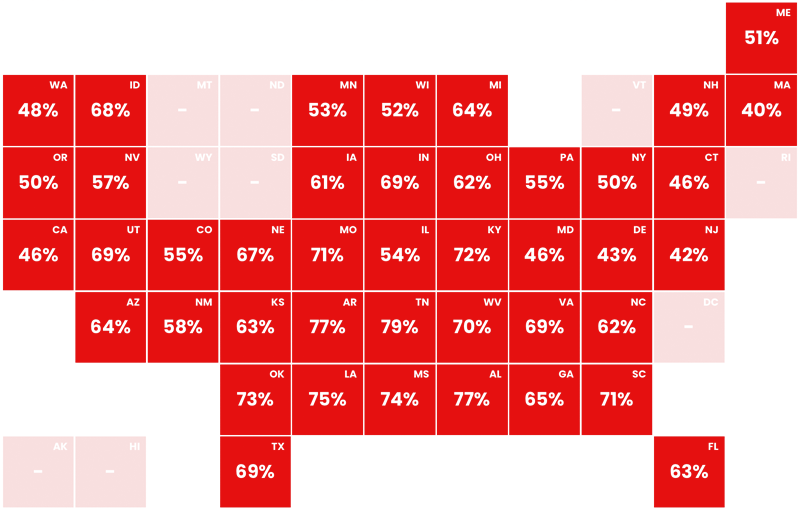

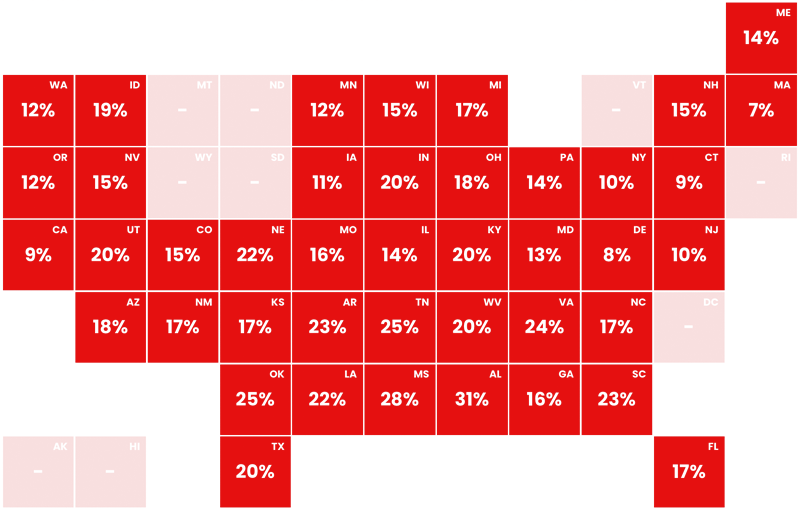

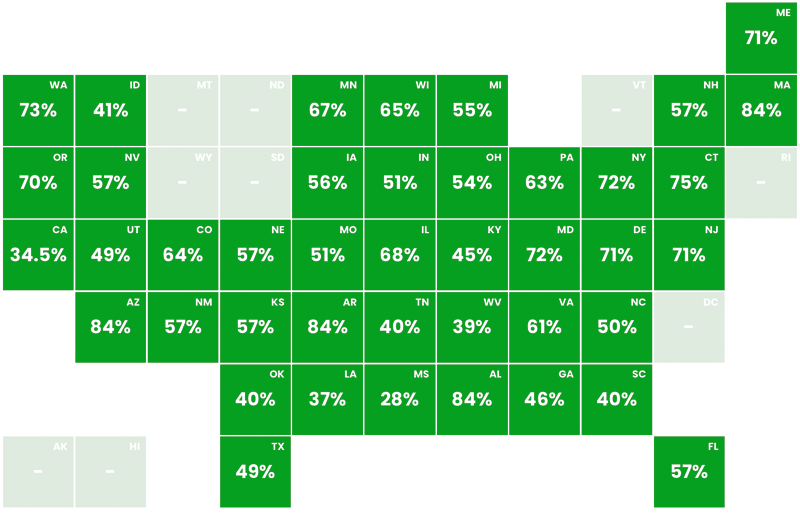

The maps below, based on an analysis by The 74 of data from GLSEN’s 2021 National School Climate Survey — the most recent available — depict more than 22,000 students’ responses regarding 10 key experiences, broken down by state. Five of the maps focus on episodes of discrimination and harassment, five on access to in-school support.

2021 National School Climate Survey

Discrimination & Harassment

Percentage of students who experienced at least one form of anti-LGBTQ+ discrimination at school

Unchanged since 2019, 59% of queer students nationwide experienced at least one form of discrimination in school, ranging from assault to being stopped from talking or writing about an LGBTQ topic or person. That average, however, obscures a wide variation. Almost 80% of queer students in Tennessee, the state with the highest reported incidence, experience discrimination in school — twice the rate as in Massachusetts, the lowest, at 40%.

The numbers are likely an undercount, researchers say. Students are hesitant to report harassment and discrimination, while school systems frequently don’t fulfill state and federal reporting requirements. Students may not be out and often fear reprisals, particularly when complaining about a teacher.

“The barriers that young people face to speaking out are very real,” says Aaron Riding, GLSEN’s deputy executive director for public policy and research. “At the school level, there’s still a lot of stigma and shame.”

But research also has found that non-LGBTQ staff may not recognize that something they are doing or that’s taking place is discrimination — even in their own classrooms. Educators in schools with policies specifically prohibiting discrimination against LGBTQ people are more likely to receive training and may be better able to recognize bias.

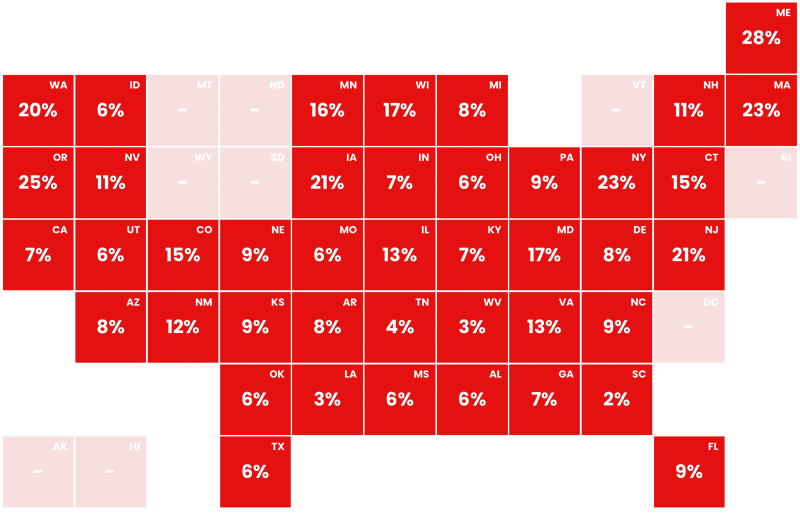

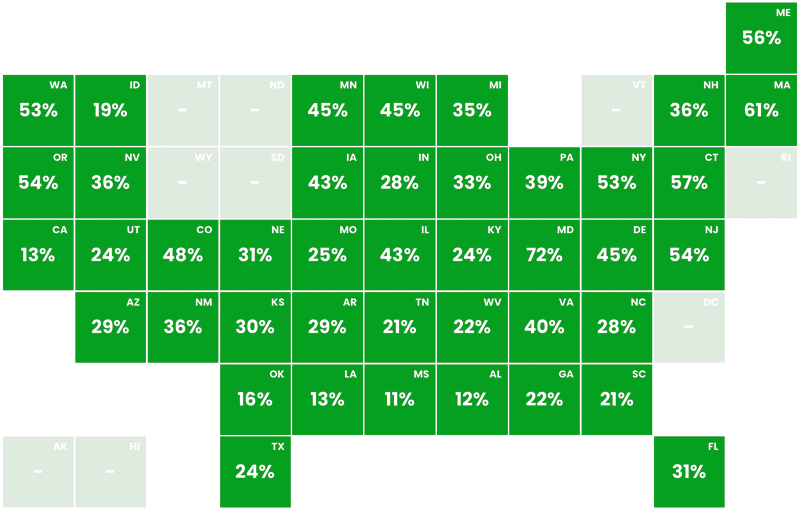

Percentage of students who say they reported victimization and received effective staff intervention

A common reason students don’t report victimization or discrimination is that they don’t believe the adults in their school will do anything about it.

“What we’ve learned over the years is that oftentimes, young people will speak out and the adults will turn around and say that they’re not going to do anything about it,” says Riding. “That is particularly harmful, because educators are the ones who set the tone for the experiences that young people have in schools.”

A 2015 GLSEN survey of educators found that only 26% said they had engaged in efforts to support LGBTQ students. Of the rest, more than half said they did not think those efforts were necessary or appropriate. More than a quarter said they feared a backlash from parents or administrators.

Historically, when “Don’t Say Gay” laws and policies are enacted, many educators are unsure if all in-school speech about LGBTQ people is outlawed and whether intervening in victimization constitutes a prohibited show of support. Twelve years ago, confusion over a policy in Minnesota’s largest school district, Anoka-Hennepin Public Schools, prevented educators from intervening against bullying, contributing to at least seven student suicides.

Adding to the uncertainty, guidelines handed down in some states go beyond their new laws. For example, last year, Florida lawmakers passed a “Don’t Say Gay” bill prohibiting in-school discussion of LGBTQ topics in elementary grades. In April, the state Board of Education — whose members are appointed by Gov. Ron DeSantis — extended the ban through high school. Soon after, the state legislature voted to enshrine a K-8 ban in law. It was not immediately clear whether the board’s policy remains in effect.

Adding to the confusion, rules handed down by the state Department of Education have taken aim at a number of things that are not included in state law, such as allowable library and classroom books, student access to anti-bullying materials, and school- and district-level guidance on supporting LGBTQ youth.

In some places, officials send mixed signals. For example, Virginia law specifically prohibits discrimination against sexual and gender minority students. But in September 2022, Republican Gov. Glenn Youngkin issued new guidance requiring schools to restrict trans students’ bathroom access and preventing students from using a new name or pronouns without parental permission, among other changes.

Critics have said Virginia’s new rules, which have not taken effect, are likely unenforceable. Some districts have said they will not follow the guidelines if they are put into place. But individual educators may not understand this legal and regulatory landscape.

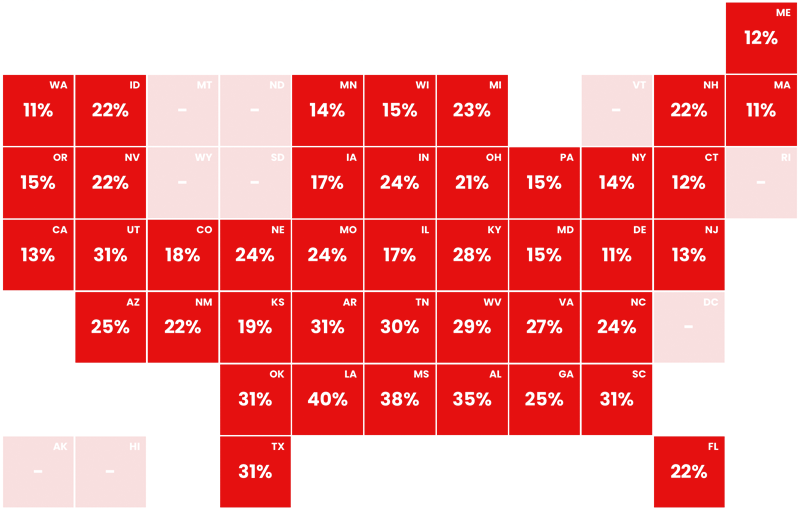

Percentage of students who were prevented from discussing or writing about LGBTQ+ topics in assignments

Seven states require schools to include LGBTQ history and culture in lessons. Yet, up to 15% of sexual and gender minority students in those states still report being prevented from discussing or writing about queer people or topics in class assignments. Similar numbers of youth were prevented from introducing LGBTQ topics in extracurricular activities.

The message students hear, Johnson adds, is, “We don’t want LGBTQ people to be a part of our society.” If a child’s parents are not accepting, the new laws choke off their other sources of support. They may no longer turn to their doctors or find a safe haven at school.

“Think about that,” he adds. “You’re not even allowed to write about your personal experience in a class where it may be relevant, or allowed to see yourself in books that are in your library…. Where can you exist?”

The youth surveyed by GLSEN are teens, but separate research suggests younger kids hear the same message, albeit likely in different ways. A recent report from the UCLA School of Law’s Williams Institute found that 15% of queer Florida parents surveyed say their children — the vast majority under age 18 — worry about talking about their families, drawing pictures of them or completing writing assignments that depict their parents.

Percentage of students who say their school’s anti-bullying/harassment policy includes sexual orientation and gender identity

Arkansas is one of 22 states with a law on the books specifically outlawing bullying and harassment of gender and sexual minority students. Yet, only 8% of youth there believe they attend a school with a policy prohibiting such victimization.

The existence of the policy, then, doesn’t make Arkansas youth any safer than students in Missouri, one of two states that has a law prohibiting schools and districts from including LGBTQ children in local anti-harassment policies. There, 6% of students say their schools have anti-bullying rules.

Most state anti-bullying laws require districts to develop their own policies, create procedures for reporting harassment and make sure students and educators understand the system for addressing complaints. When young people don’t know the policies exist, by definition there is an implementation problem, says Riding.

“School districts have a lot of autonomy and not a lot of enforcement in terms of adopting a policy and implementing it in schools,” he says. Surveying students to gauge awareness, Riding adds, “helps us know that districts and schools are ignoring those standards.”

While there is no federal anti-bullying law per se, the U.S. Civil Rights Act prohibits in-school discriminatory harassment. Sexual and gender minorities are protected by these laws, which outlaw hostile environments that interfere with a student’s ability to benefit from a school’s activities and opportunities.

Percentage of students who were prevented from wearing clothing deemed ‘inappropriate’ based on gender

In Louisiana, 40% of students surveyed said they were prevented from wearing clothing school staff did not think was appropriate for their gender. Rates were nearly as high in Mississippi and Alabama, and above 30% in numerous other Southern states. Slightly lower numbers say they were told they could not wear clothing with LGBTQ-supportive messages.

To queer kids, this sends the same message as excluding LGBTQ topics and people from assignments and class discussions, says Johnson. “If you wear a rainbow shirt to school, and you are sent home for it, or you are made to change that shirt, it’s not just about the shirt,” he says. “It’s about saying, ‘People like you … are not welcome here. And not only does it say it to the one kid who is forced to take a button off their backpack, it says it to all the other kids: That kid isn’t welcome here.’”

But it also reinforces traditional gender roles, he says. In Utah, which last year banned transgender students from playing on girls’ sports teams, officials have heard from parents who say their daughters lost to competitors who did not seem feminine enough to be cisgender.

2021 National School Climate Survey

Access to in-school support

Percentage of students who have access to a gay-straight alliance

Gay-straight alliances — in-school clubs for queer kids and their allies — have flourished since the late 1980s, in part because courts have repeatedly ruled that federal law guarantees students at public schools the right to form them. Virtually all the relevant lawsuits were brought by students.

GSAs provide a supportive network of peers for students who are exploring their identity or attempting to survive discrimination or harassment. They are organized by students, who typically approach a sympathetic staff member — often the school librarian — to be the club’s adviser.

A trove of research confirms the clubs’ positive impact for non-LGBTQ students, too. One 2016 study found that all students at schools with GSAs have 30% lower odds of experiencing homophobic victimization than peers at schools without a club, 36% lower odds of fearing for their safety and 52% lower odds of hearing homophobic remarks. Other reports have found GSAs have a positive impact on a school’s overall environment.

The first GSAs were started in Massachusetts, where 68% of teens now report having access to one. In several Southern states, that number drops as low as 8%, but there are some red states with strong GSA movements. A third or more of students in Florida, Arkansas, Kansas and Arizona, all of which recently have passed anti-LGBTQ laws, report their school has a GSA.

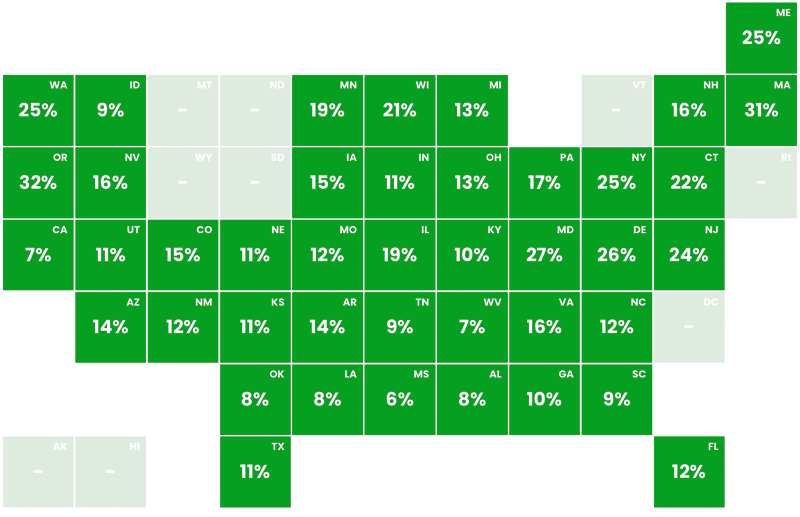

Percentage of students who can identify six or more supportive school staffers

Even in the most inhospitable schools, most LGBTQ students can name one teacher they believe to be supportive. The number drops, though, when youth are asked whether they can identify six. While it’s not an exact barometer — small schools or schools in small districts may not employ enough teachers for six to be LGBTQ-accepting — this survey question is a rough measure of school climate. A student’s ability to name one affirming teacher can mean that individual student has a lifeline, but the existence of several suggests a school welcomes queer adults and kids alike.

In Louisiana, 91% of LGBTQ students surveyed could name one supportive staff member, while only 37% could identify six or more. In Washington state, 99% could name a single staffer, while 73% knew of six.

One possible factor, says Ryan Watson, a professor of human development and family studies at the University of Connecticut, is that the schools that have several are places where LGBTQ-supportive teachers want to work. Teachers who themselves are sexual and gender minorities also risk repercussions in schools with hostile climates.

In a 2020 GLSEN survey, 75% of LGBTQ teachers said they had implemented affirming practices such as serving as a GSA adviser, making sure stickers and other signs of support are visible, advocating for inclusive practices or informally discussing queer topics with students. Of non-LGBTQ educators, 49% had engaged in a supportive activity.

Percentage of students who reported their school administration was supportive

Surveys have consistently found that in the face of possible parental backlash, district and school administrators often tell teachers to limit classroom discussion of hot-button topics. Even when they don’t, teachers frequently fear that their department head or principal will not back them if there are complaints from parents and anti-LGBTQ protesters.

A 2022 RAND Corp. survey of educators found it did not matter if the opposition came from just “a vocal minority” of parents. Some said their administrations have limited the materials they can use, instituted vetting processes and begun conducting — or allowing parents to conduct — classroom “audits.”

In 2020, GLSEN found that a third of LGBTQ teachers and one-fifth of non-LGBTQ educators said community backlash and fear of it prevented them from supporting sexual and gender minority students. Ten percent of straight, cisgender educators and 21.5% of queer ones cited unsupportive administrations.

More than a third of LGBTQ teachers said they feared they would lose their job if they came out to an administrator, despite a Supreme Court ruling that this is illegal discrimination.

Percentage of students who were taught positive representations of LGBTQ+ people, history or events

Attending a school in one of the seven states that mandate positive depictions of LGBTQ people and history in classroom instruction is no guarantee a student will receive it. In Massachusetts and Oregon, slightly less than a third of youth reported being exposed to such material, a rate that falls to just 7% of students in California, which 10 years ago became the first state to require inclusive curriculum.

There are a host of reasons for this disconnect. Large publishers balked at revising their textbooks to meet California’s standards, for instance. The companies said they were unable to verify how historical figures might have identified, but critics pointed out that the change would have impacted their bottom line, since they could not sell the same materials in states that explicitly forbid LGBTQ content.

A 2017 report found that half of English language arts teachers said they are comfortable using literature that contains LGBTQ characters or storylines in their lessons, but only 24% of them actually incorporated such materials.

More educators — 61% — were comfortable with students choosing queer-themed books to read for pleasure, the report noted. While this may be a safer choice for a teacher who is unsure what book to assign, it’s not ultimately as helpful to students as having everyone read and discuss the same text.

Separately, a report published last summer by the group Educators for Excellence found 1 in 3 teachers doesn’t think LGBTQ history and experience should be taught in schools, while 11% believe their school does not enroll any gender or sexual minority students.

Percentage of students with access to inclusive library resources

Libraries have long been sanctuaries for queer youth, and in part because of the special training they typically receive, school librarians often serve as GSA advisers. The American Association of School Librarians has an entire division devoted to evaluating the quality, content and age-appropriateness of LGBTQ books and other school resources.

According to the free-speech advocacy organization PEN America, between July 2021 and June 2022, there were more than 2,500 book bans, with the largest number occurring in Texas, Florida, Tennessee and Pennsylvania. Forty-one percent were of books featuring LGBTQ themes or characters.

The ferocity with which the bans are pursued can create the impression that school libraries are replete with LGBTQ titles. But even in Maine, the state where the most students have access, one-third say their school library lacks books with queer characters or themes.

Interactive maps and graphics by Eamonn Fitzmaurice / The 74.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter