How Libraries Came to be Sanctuaries for LGBTQ Kids

After Stonewall, librarians were the first profession to organize for gay rights. Meet the pioneer who led the charge — and now fears for his legacy

By Beth Hawkins | June 29, 2022In May 2021, as efforts to ban books on LGBTQ topics from school libraries were gaining political steam, “Two Grooms on a Cake: The Story of America’s First Gay Wedding” was published. It is a children’s story about Michael McConnell’s 1971 marriage to a man, which was upheld as legal by the U.S. Supreme Court in 2015.

But McConnell isn’t just a protagonist in a book; as a librarian, he was instrumental in transforming libraries into the kind of welcoming places for LGBTQ kids that he craved as a boy.

It’s largely because of him and a handful of colleagues that library shelves today have space for books like “Two Grooms” — a historic accomplishment that McConnell, now 80 and enjoying a quiet retirement in Minneapolis with his husband, worries is endangered.

Since the slender storybook’s release, some 1,600 books with LGBTQ and racial-equity themes have been challenged in dozens of states, according to the free speech advocacy organization PEN America. It’s the highest number of book challenges recorded by the American Library Association since it began tracking bans 20 years ago.

“I suspect it’s probably by now been banned in Florida,” McConnell says. “I can see what’s coming. … We’ve got a fight on our hands.”

Historically, LGBTQ-related books are among those most stolen from libraries — a metric that librarians, oddly or not, still use to gauge demand when ordering new volumes, despite decades-long efforts to reduce the stigma of browsing for books about queer people. In fact, while his status as one of the first gay grooms may be what most visibly enshrines McConnell in history, he played a pivotal role in creating library shelf space for “boy meets boy” tales such as his — as well as a wide array of LGBTQ fiction and books about queer history, culture, health care and other resources.

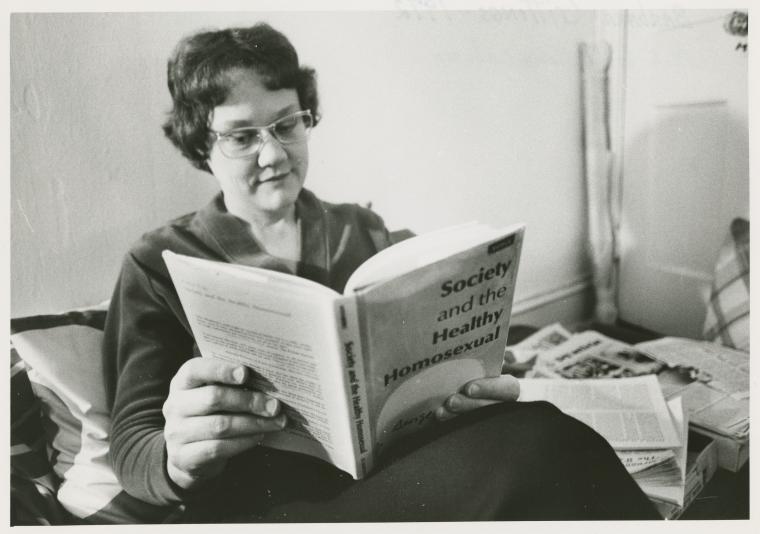

As a child, McConnell secretly visited the library looking to understand his same-sex attraction — and, finding no help, went on to a career as a librarian with a special interest in curating collections of LGBTQ books.

Indeed, current-day librarians credit McConnell’s accomplishments — everything from convincing publishers that libraries would provide a market for positive portrayals of queer people to replacing pejorative subject headings in card catalogs — for helping to provide safety and privacy for youth and adults as they seek out information.

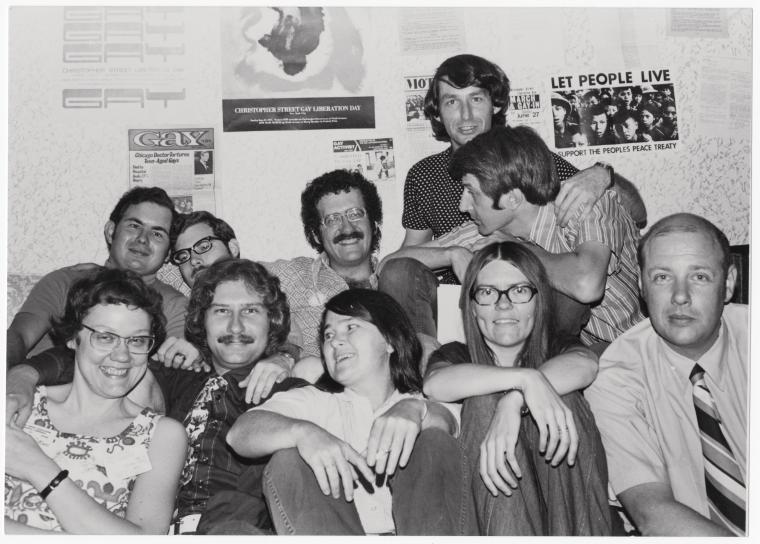

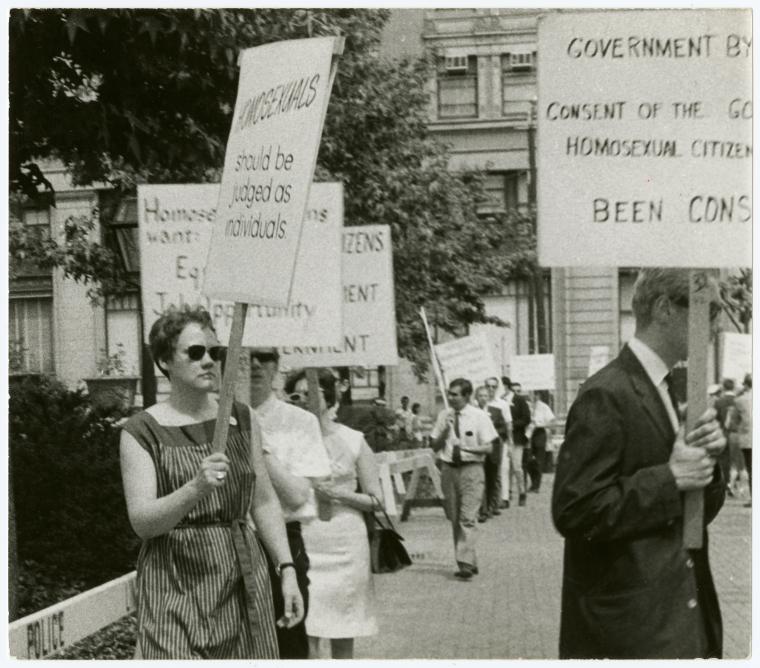

K-12 school librarians, for example, often receive regular training in how to accommodate LGBTQ students and are frequently the staff member who sponsors the school’s gay-straight alliance. This work is a direct outgrowth of advocacy by McConnell and a small group of colleagues who, in the immediate aftermath of the Stonewall uprising in June 1969, organized the American Library Association as the first professional group with a queer committee formally advocating for LGBTQ rights.

McConnell’s story is a variation on a common one. In middle school, he walked from his home in Norman, Oklahoma, to the local library. While he was certain there was nothing wrong with him, he didn’t know why he was different or how to find other people like himself. It took some sleuthing, but he eventually found the right shelf at the nearby University of Oklahoma library — and, to his teenaged chagrin, a selection of titles that seemed designed to ruin his self-esteem.

“Most of it was negative and most of it psychological,” he recalls. “And — how shall I put this? — lies.”

Depictions of LGBTQ people living normal, fulfilling lives, he came to learn, mostly did not exist. “Publishers were afraid in those years to put out positive titles,” he says. “I knew during this time of great closetry for the community, and no information available except lies, that I was going to have a hard time — and the library was the answer.”

Another Stonewall-era activist with the American Library Association, the late Barbara Gittings, made her own exploratory trip to the library as a college freshman in 1949. “When I speak to gay groups and mention ‘the lies in the libraries,’ listeners over 35 know instantly what I mean,” she wrote in “Gays in Libraryland: The Gay and Lesbian Task Force of the American Library Association: The First 16 Years.” “Most gays have at some point gone to books in an effort to understand about being gay or to get some help in living as gay.”

More than half a century later, despite current headlines, gay-related resources in any library — adult, university, K-12 — are plentiful. What was born as the association’s Task Force on Gay Liberation has evolved into the Rainbow Round Table, which screens LGBTQ-themed books and bestows awards on the best. This year, “Two Grooms” was named a top-10 title for younger readers.

A division of the larger organization, the American Association of School Librarians, offers a wealth of resources for educators, librarians and families. In 2018, it published “Defending Intellectual Freedom: LGBTQ+ Materials in School Libraries,” which, among other guidance, helps school staff explain and defend standards for what youth media centers should offer.

GLSEN, a national nonprofit that supports schools to be safe places for LGBTQ students, offers Rainbow Libraries, free, boxed sets of age-appropriate books. Now in 1,800 schools in 28 states, the 10-book collections include stickers with the group’s web address, posters and other classroom resources that let young readers know that the library offers even more.

“We hear all the time that students can’t wait to get their hands on these books,” says Michael Rady, GLSEN’s Rainbow Library manager. “In Kansas, a librarian processed their new books on a Friday and shelved them immediately. By Monday, they were all checked out.”

Many of the ways in which present-day librarians try to ensure welcoming environments are outgrowths of strategies generated by Stonewall-era librarians. For instance, “Serving the Faithful Reader,” a 1976 series of skits, taught reference desk staff how to react to fearful visitors who might not be able or willing to say outright what they are after.

School librarians are urged to set out books that feature LGBTQ youth of different identities, races, ethnicities and backgrounds not just for Pride month, but for showcasing other holidays or themes, says Rachel Altobelli, director of library services and instructional materials for Albuquerque Public Schools and a member of the group that authored the intellectual freedom report.

That way, all kinds of kids see themselves without having to ask, or even necessarily be looking for LGBTQ information — they might be fantasy fiction fans or get sucked in by graphic novels, she says.

Librarians in Altobelli’s district are trained to understand that they may never know which books made a difference for which kids — and that’s a good thing. More children are coming out at younger ages than ever before, she notes, but lots still “want to be able to figure things out in their own time in their own way, and they don’t need any random grownups to know.”

“We tell our librarians, with some kids, ‘You’re not going to have that big, beautiful, magical moment where they come in and thank you,” she adds. “But you nonetheless saved their life, and you might never know.”

Library privacy topped the 1970s Task Force on Gay Liberation agenda, too. Presentations for librarians included “Closet Keys,” which focused on good LGBTQ periodicals to subscribe to, and, “You Want to Look up WHAT?” covering how to index them.

McConnell, Gittings and their contemporaries were determined to end the practice of forcing visitors to search through catalog cards bearing headings like “sexual deviance” and “sexual predation.” Along with librarians from other demographic groups demanding better representation, they pushed the Library of Congress to change a number of classifications.

“That put us into positive (shelving classification) numbers,” recalls McConnell, in turn enabling readers to be less secretive.

The early task force also considered what it called “the stolen-book problem,” a phenomenon Altobelli and Rady say continues to this day. Whether LGBTQ-themed books disappear from a library’s inventory because students are embarrassed to check them out and simply take them, or don’t return them because they have no other sources of factual information, the rate at which the titles need to be reordered is something librarians see as a gauge of popularity.

As the current wave of anti-LGBTQ legislation has swept the country, demand for GLSEN’s Rainbow Libraries has increased, says Rady, who hopes to increase the number of schools with sets of books to 3,000 by the end of the year. The debate’s inflammatory tone, he says, has posed particular problems for youth in communities that have little LGBTQ visibility.

“It’s really hard to be closeted. It’s really hard to come out. It’s really hard to be the only LGBT person in your community,” he says. “We’ve heard from librarians how it’s the first time [students] can dive into someone else’s story and see themselves.”

Helping people see a good life for themselves was, of course, McConnell’s goal when, freshly hired by the University of Minnesota to acquire books for its libraries, he wed Jack Baker. Baker had gone to law school specifically to find a legal path to marriage. In the face of the publicity that attended the nuptials, however, McConnell was fired.

(The university has since apologized, and houses McConnell’s work-in-progress archive in its Jean-Nickolaus Tretter Collection in Gay, Lesbian, Bisexual and Transgender Studies.)

Using a license legally obtained in Blue Earth County, Minnesota, the two got married anyhow, in a 1971 ceremony with a hippie aesthetic faithfully depicted in “Two Grooms.” After, they fought for the validity of their union all the way up to the U.S. Supreme Court, where it was dismissed in a single sentence.

When the court recognized marriage equality in Obergefell v Hodges in 2015, the justices made sure to reach back half a century and issue a new decision in McConnell’s case. “The court now holds that same-sex couples may exercise the fundamental right to marry,” the jurists wrote. “No longer may this liberty be denied to them. Baker v Nelson must be and now is overruled.”

“Two Grooms,” which uses a cake-baking metaphor to illustrate the process of nurturing a relationship, isn’t the only account of Baker’s and McConnell’s marriage that can be found in public libraries today. They would like to keep it that way.

“ ‘Don’t say gay,’ ” he scoffs. “Sweetheart, we got over that 50 years ago.”

So what would McConnell say to a student who goes into a school library where books like his have been removed?

“I would say talk to someone that you know loves you and that you feel safe with and tell them,” he says. “I know that that’s scary. But is there someone that you feel safe with you can do that?”

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter