Rural Teacher Prep Program Delivers ‘Job-Embedded’ Degrees — For $75 a Month

Reach University candidates gain BAs and teaching certifications for just $1,800 while working and earning a salary in high-needs Arkansas districts

Get stories like this delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

Updated, Oct. 12

Working in a region of rural Arkansas long plagued by teacher shortages, Eveon Rivers seems like the perfect candidate to lead a classroom. With 18 years of pre-K teaching experience, she knows how to work with young people. And a self-described “Greek mythology person,” she has a passion for high school history — the subject she wants to teach.

She’s missing just one qualification: a bachelor’s degree.

Now, a program that aims to combat rural teacher shortages by upskilling qualified school staff is helping her actualize her dreams — at a bargain price. Rivers pays $75 per month and has only three more semesters left before she graduates and can get her teaching certification.

“Who can beat a BA for $1,800?” said the veteran educator. “That’s a no-brainer.”

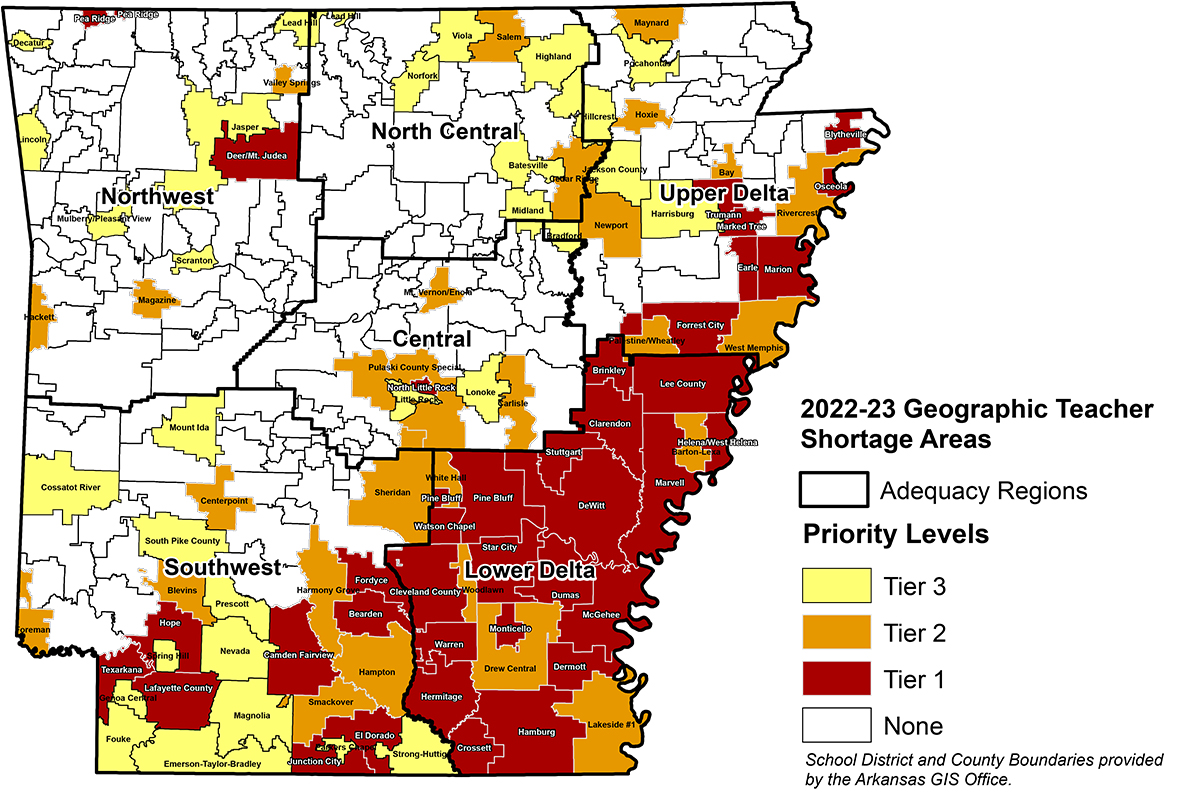

Across large swaths of Arkansas, the problem of persistent teacher shortages predated the pandemic, but has “become more apparent” over the last few years, said Karli Saracini, the state’s assistant commissioner of educator effectiveness. In many districts, especially in the southeast Delta region, over 10% of teaching roles are now held by unlicensed educators, according to state data.

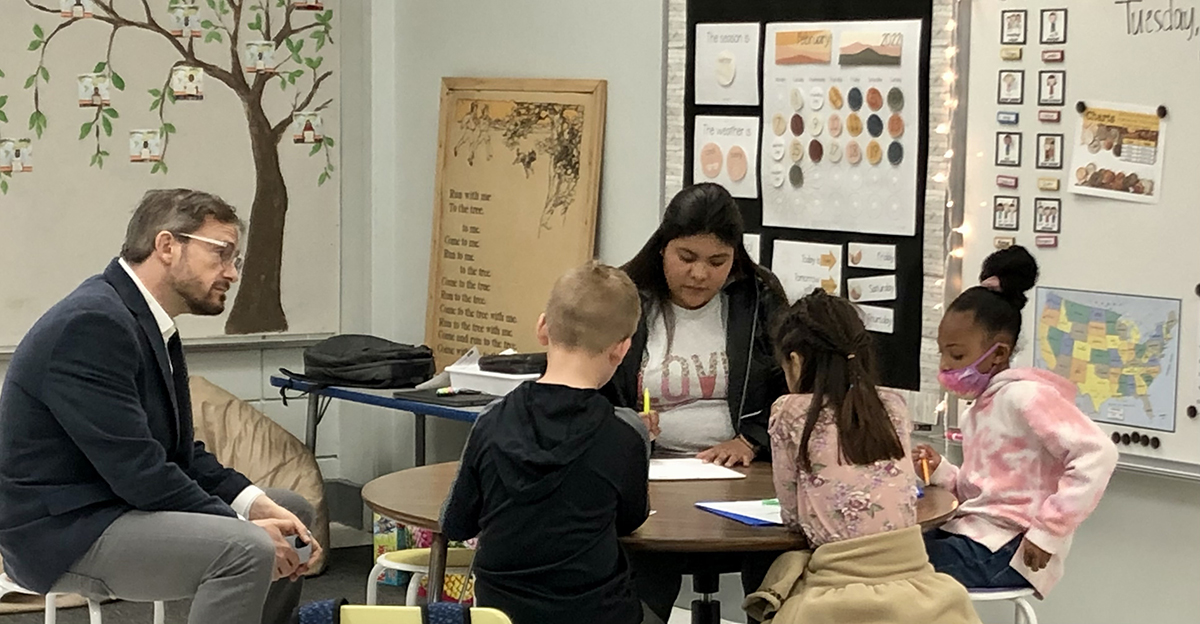

Joe Ross, president of California-based Reach University, believes the solution lies close at hand. Nationwide, over a million paraprofessionals work side-by-side with lead teachers, he points out, and many have the know-how to step into greater responsibility. His school’s model, he said, helps eliminate financial and geographic barriers for those educators so they can gain the credentials necessary to lead a classroom.

“The degree is fully job-embedded from the very first day to the very last day,” Ross explained, meaning candidates continue earning a salary in their existing jobs all the way through the program. Thanks to Pell grants and funding the school receives as an apprenticeship provider, no student pays more than $900 per year, he said, and the program is free for participating districts.

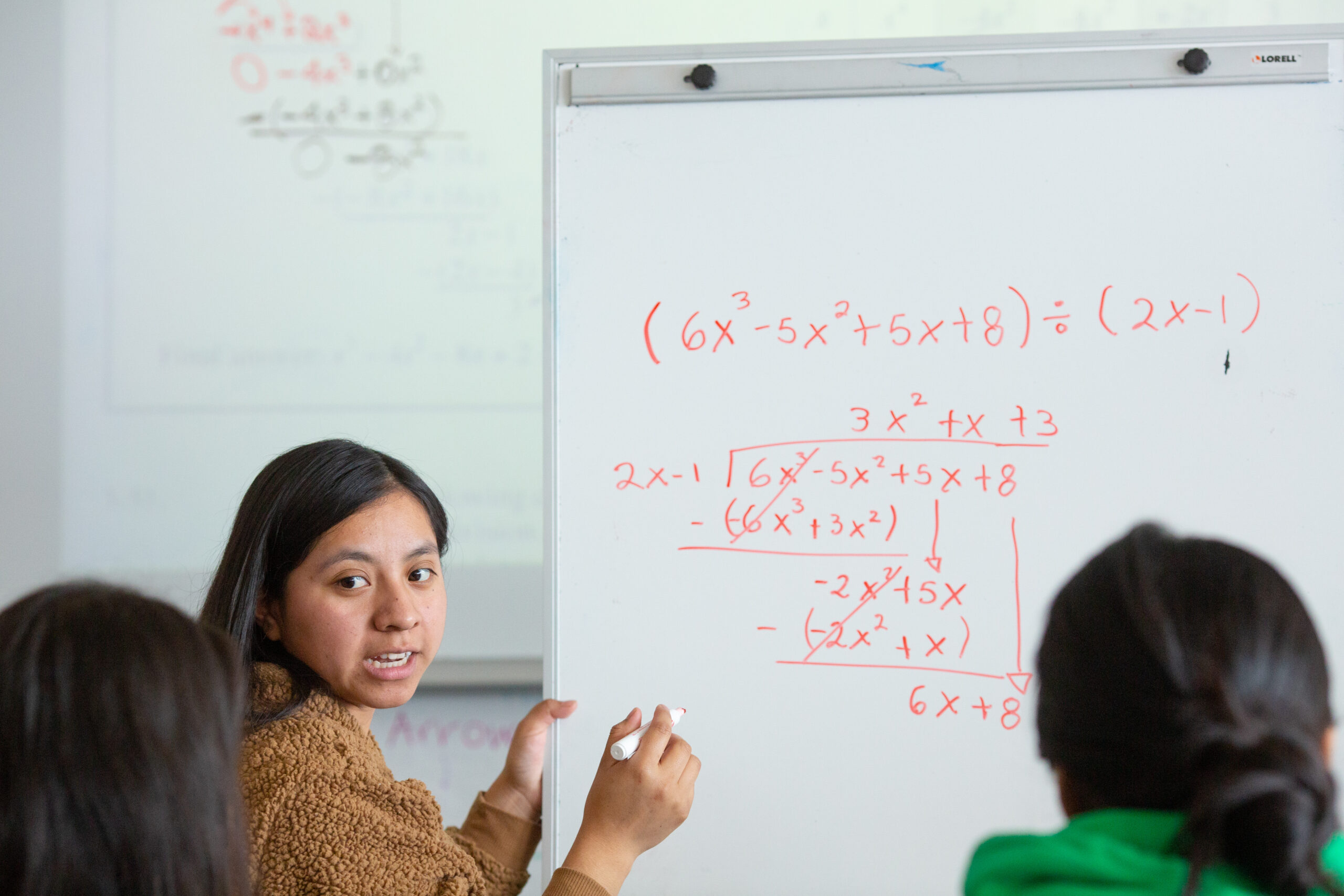

To be eligible, candidates must be employed in a partner school system. They complete half of their degree through on-the-job work, including workplace-based assignments, such as observing and reflecting on the techniques of a veteran teacher, and practicum-style courses that award credit directly for their efforts in the classroom. The other half of the degree comes through online seminars held after work hours and on weekends designed to help the future teachers apply theory to what they’re learning on the ground.

Reach University already serves over 250 learners in Arkansas and roughly 1,000 nationwide. Now, the program is poised to grow even further. In September, the U.S. Department of Education granted Reach University more than $8 million to place some 650 fully certified teachers into high-needs Arkansas classrooms over the next five years. And in late September, Reach received another $6.9 million from the education department to grow its teacher training efforts in Louisiana and is a partner in a separate $10.7 million grant in that state received by Tulane University. Outside Arkansas and Louisiana, Reach also serves educators in Alabama and California.

In Arkansas, at least half of the educators trained by Reach will be teachers of color. In 2020-21, more than two-thirds of districts in the state did not employ a single Black, Indigenous, Hispanic or Asian teacher of record, despite some 40% of students holding those racial identities.

“It can change the teacher force by truly opening doors that are currently shut for way too many people,” said David Donaldson, managing partner for the National Center for Grow Your Own educator pipeline programs. There’s recently been a “massive increase” in school officials’ interest in such programs nationwide, he said. But Reach, founded in 2006, is one of the organizations with the most effective and accessible models, he believes.

“To see them spread across the country, they’re really doing good work.”

Some 90% of Reach graduates in Arkansas will be re-hired in the same district after they complete the program, according to the federal grant award. It’s a boon in the eyes of Carolyn Theard-Griggs, dean of the National College of Education at Chicago-based National Louis University.

“People have a tendency to stay in schools longer if they’re near their home base,” she observed.

The expansion is much needed, said Saracini, of the Arkansas state education department. Too many otherwise-qualified staff get boxed into lower-paying positions like classroom aides because they can’t afford to go back and study for a degree.

“The people who would make some of our best teachers are some of those paraprofessionals, but they just can’t break that employment and lose those benefits,” she explained. When they do land full-time teaching gigs, however, their pay can more than double.

Furthermore, the training model, Ross argues, mints educators with stronger teaching skills than traditional programs that often graduate and certify candidates after just a semester of student teaching. Reach educators have at least two years working in the classroom under their belts by the time they complete their degrees.

“That will create better teachers,” said the university president. “It will create a rank of graduates who are respected for having this degree.”

Rivers, who will graduate at the end of 2023, agrees.

“I have all this experience. I feel like I’ll be a seasoned teacher,” she said. Her district outside Little Rock, she added, has a job awaiting her when she becomes licensed.

“I want to be a cool history teacher. I want to make it fun for the kids. … I want to dress up, do the props.”

For now, on her paraprofessional salary, Rivers has to deliver UberEats and Grubhub in the evenings to make ends meet. On nights her delivery work and course schedule overlap, she sometimes uses a phone stand in her car to join class.

“I like the leeway where I can tune in on my phone,” she said. “It’s so accessible.”

Many of the Arkansas school systems facing the most dire need for licensed teachers, Saracini explained, are also areas where higher education is the least accessible, with no nearby options for four-year degrees. Reach fills in the gap, expanding “in some of our most-needed areas,” she said, by offering a model where candidates can build on their community college credits without needing to commute.

Years ago, Rivers was able to complete her associate’s degree while working pre-K, but lacks her bachelor’s. She had previously worked toward a BA, but was forced to stop when her financial aid dried up.

When she found out about Reach, it was her “saving grace,” she said. “It’s affordable, it’s flexible and the professors are good.”

Now, she talks about the program to anyone who will listen.

“I tell a lot of people about it,” she said. “A lot of people have been in the school system a long time and a lot of people are just starting. So, if you’re going to be there, why not further your education?”

Disclosure: Walton Family Foundation and the Stand Together Trust provide financial support to Reach University and The 74.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)