‘Untapped Talent’: TA to BA Teacher Prep Program Scales Six-Fold Amid Shortages

Two years in, fellowship training teaching assistants into lead teachers expands to new cities and “grow-your-own” programs are taking hold nationwide

Get stories like this delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

Updated

Rosemely Osorio is swiftly becoming the educator that, years ago, she wished for.

When, at age 9, she and her family came to Rhode Island from Guatemala, Osorio recalls struggling academically as she navigated an unfamiliar system.

“When I came here and I started at the schools, I remember, I didn’t know how to speak any English. … I didn’t have a mentor who told me, ‘Hey, it’s really important that you work extremely hard in high school so then your GPA is good.’ I didn’t know what a GPA was,” she said.

In 2014, she graduated high school, the first in her family to accomplish the feat, but college remained out of reach because of finances and her immigration status — Osorio is a DACA recipient, the Obama-era program that provides deportation relief and work permits to undocumented residents brought here as children.

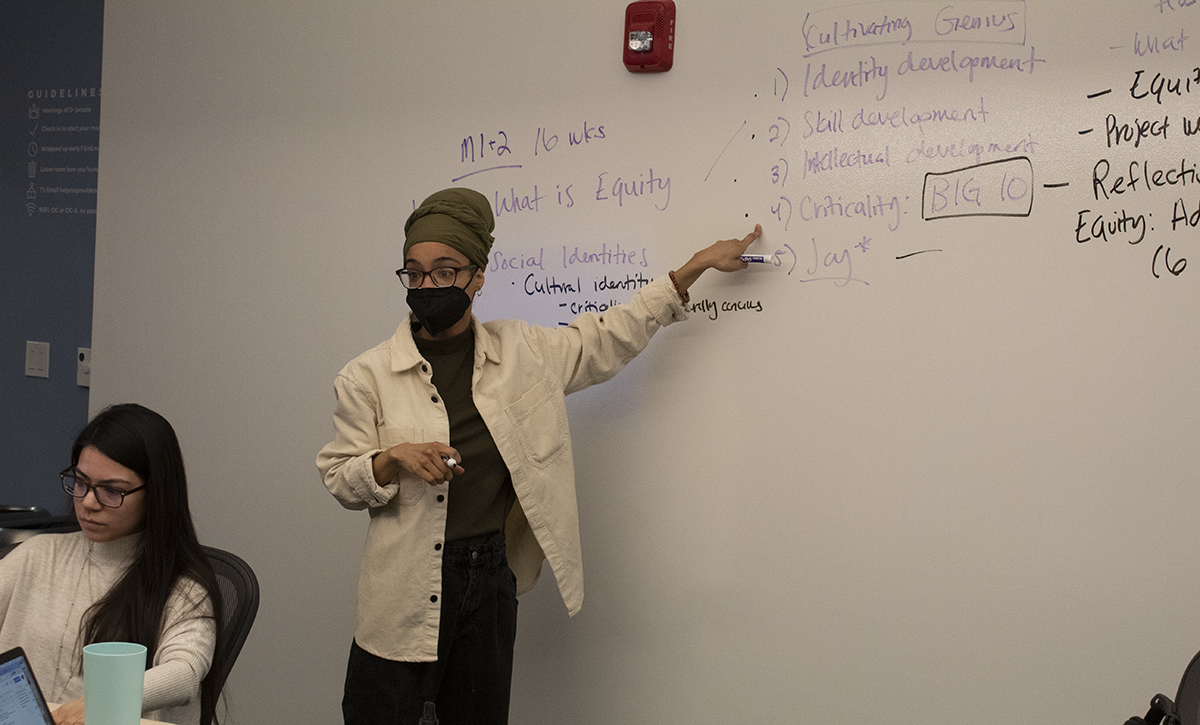

Now, years later as an adult learner in College Unbound and the Equity Institute’s TA to BA program, she’s just a semester away from earning her bachelor’s degree and teaching certification, key steps toward becoming exactly the role model she yearned for as a young person. At the same time, she works as a paraprofessional in the Central Falls high school she once attended, which serves a high share of Central American immigrant students.

“They see in me someone that they can count on,” said Osorio. “They’re like, ‘Oh, she knows how to speak Spanish. She looks Hispanic. So I can actually talk to her.’”

After only two years in operation, the teacher training program that opened doors for Osorio has scaled up more than six times beyond its original capacity and is launching cohorts in a second city, with talks underway to expand to a third, leaders say.

“The program has grown pretty tremendously,” said Carlon Howard, who helped launch the TA to BA fellowship and is chief impact officer at the Equity Institute. “There’s a lot of interest in initiatives such as these given that, across our country, schools and districts are challenged to find enough educators to staff their buildings.”

The Rhode Island program, which served 13 fellows in its inaugural 2020-21 class, will train 75 paraprofessionals this year. Two new, 10-student cohorts will launch in Philadelphia, where College Unbound already operates other programs, thanks to funding from the school district. Over 40 people remain on the waiting list, said David Bromley, College Unbound’s Philadelphia coordinator. In nearby Camden, New Jersey, the college is working with the teachers union to roll out programs there, too, he added.

“Investing deeply in our staff who already work closely with our students to bring them to the next stage of their career is a shining light of positivity in the midst of a difficult few years,” Larisa Shambaugh, chief of talent for Philadelphia public schools, said in an emailed statement to The 74.

‘Untapped talent’

Many paraprofessionals are highly skilled educators with years or even decades of classroom experience, Howard said, but still may feel like they have a “glass ceiling above their head” because they lack college degrees and financial resources.

Participants in the fellowship often study tuition-free thanks to the Equity institute’s “last dollar” scholarships covering costs not offset by federal Pell grants.

“We target folks who already work with kids … and all we’re trying to do is help them realize their greatest potential,” Howard said.

TAs are an “untapped talent” pool from which to recruit and train high-quality educators, agreed David Donaldson, managing partner for the National Center for Grown Your Own educator pipeline programs.

Students take two College Unbound courses a semester, scheduled outside of the work day, plus a lab component specifically geared to prepare them to lead a classroom. Thanks to a process at the college for measuring and awarding credits for prior learning experiences, some students are able to take an accelerated path to graduation. Osorio, for example, will finish in under two years.

“It’s been a lot of work,” she admits, cramming in classes while also working full time and taking care of family responsibilities. “But I don’t regret it.”

Addressing diversity, combatting shortages

Educators like Osorio — those who reflect their students culturally and linguistically — are in short supply in Rhode Island’s schools and nationwide. Roughly 1 in 10 teachers in the Ocean State are people of color while 4 in 10 students identify as Black, Hispanic, Indigenous or Asian. Meanwhile, educators of color and those who speak multiple languages improve outcomes for all students, but provide a particular boost to students whose identities they match, research shows.

Classroom aides, on the other hand, tend to be much more racially and linguistically diverse than teachers. The positions generally do not require a college degree and can be more accessible to people from low-income backgrounds. All her fellow teaching assistants, Osorio said, speak Spanish and the vast majority are people of color, whereas the teachers at her school are predominantly white and speak only English.

“To be honest, everything we see is all these teachers in the classrooms with a bunch of Hispanic kids, but the teacher doesn’t speak their language,” said Osorio. “That’s what my biggest motivation was to apply and getting certified was that students need teachers in the classroom that they can relate to.”

David Quiroa is joining the TA to BA fellowship this fall and works as a paraprofessional in his home community of Newport, Rhode Island.

“So many TAs who are in the [Black, Indigenous and people of color] community already have been putting in the work for several years … and they’re never given the opportunity to pursue higher education,” he said. “With TA to BA and College Unbound, it really is showing these communities, ‘Look, we are here, we are federally approved, we have all of the accreditations, we have so (many) established connections here in our community. You guys have been doing the work. We just want to give you your proper salary.’”

Meanwhile, districts across the country are facing acute staffing shortages and going to extreme lengths — including tapping college students or dangling $25,000 bonuses — to entice new hires.

In this climate, the grow-your-own approach is “getting a lot of attention now,” Donaldson said, even though turning to programs that provide a work-based pipeline to train new teachers is a longer-term solution.

His organization recently announced that seven states with existing or emerging apprenticeship programs to train educators launched an all-new National Registered Apprenticeship in Teaching Network. It comes on the heels of a June announcement from Education Secretary Miguel Cardona urging states to invest in grow-your-own programs, including those that begin in high school and with apprenticeship programs.

“Missouri, like other states, is struggling to address staffing issues created by teacher shortages. The Teacher Apprenticeship is an additional, innovative model to help address this issue,” Paul Katnik, Missouri’s assistant education commissioner, said in a release after the network was announced.

The other participating states are California, Florida, North Dakota, Texas, West Virginia and Wyoming.

‘We got you’

The relationship faculty build with participants is a secret to the program’s success in Rhode Island, and soon in the new Philadelphia cohorts, fellowship leaders and students say.

Osorio’s advisor “has played a big role in the way that I have been able to develop in this program,” said the College Unbound student. In addition to checking in academically and emotionally, the faculty member who runs her teaching lab class allowed Osorio to make up credits when she fell behind after a devastating miscarriage. And when Osorio was short on cash to renew her Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals status and fearing she would lose her work permit, she again asked for help.

“Don’t worry about it. We got you,” was the response from College Unbound. “And they actually sent me a check home so I could pay for that application.”

That support is by design, said Howard, who explained that the program trains its faculty to uplift participants and be there for them. Even as the fellowship scales up, he’s confident the family-like culture among cohorts will remain.

The TA to BA leader believes it’s within the program’s reach to train 200 paraprofessionals into full-time teachers in the next three to five years. If all goes according to plan, he hopes to serve 500 by 2030 and may also add a high school teaching apprenticeship component.

Quiroa, the Newport TA, is “thrilled” about the expansion, he said, because there are “absolutely” others in his field who could benefit from the opportunity. “Having this organization, this program, thrive … I think is the best thing we can do to move forward and break a lot of these inequities.”

Osorio, for her part, can visualize the impact that seeing someone like her at the helm of a classroom could have for immigrant students. Hispanic role models were vital in her professional life after graduating high school, she said, and now she can finally pass on the favor.

“I get how important mentors are so now I can be that for those students.”

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)