Review: In Dale Russakoff’s “The Prize,” an Urgent Education Catastrophe Overflowing with Culprits and Caveats

The subtitle of Dale Russakoff’s new book, “The Prize: Who’s in Charge of America’s Schools?”, ought to give readers a moment’s pause. It’s not immediately obvious why “Who’s in charge?” should be a primary question as far as America’s schools are concerned. And yet, who “runs” the schools is ground zero for so many of education debates. Wars over control of curricula, school schedules, personnel, and basic achievement objectives are some of the fiercest fights in American public discourse — especially in urban education systems.

Nowhere have these fires burned hotter in recent years than Newark, New Jersey. As Russakoff puts it, Newark’s schools are “facing fiscal ruin, massive overcapacity, and in urgent need for improvement.” Which is more emblematic than exceptional, as far as struggling urban school districts are concerned.

Newark is just one of a number of cities where battles over governing education have recently flared. New York City’s ongoing fight between the district and some of the Big Apple’s most successful public (charter) schools is fundamentally about who runs public schools — mayors or educators. New Orleans, Chicago, Washington, D.C., and Los Angeles have gone through similar convulsions.

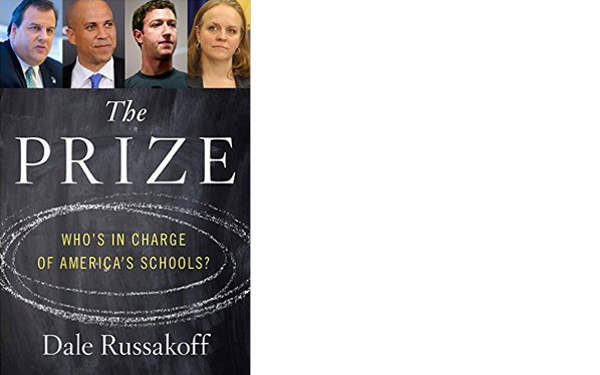

But Newark’s education conflagration is unique. “The Prize” tracks Newark’s last five punchdrunk years converting a promising opportunity into one of the roughest recent reform battles in American education. It all started with a windfall: An Oprah-announced, five-year, $100 million donation from Facebook founder Mark Zuckerberg (a sum local donors would eventually match).

And Newark’s good fortune didn’t end with the sudden cash infusion. Russakoff opens the book on a dark and stormy night, with two politicians sliding through a rough part of town talking education policy. One is New Jersey’s Republican Gov. Chris Christie — who Russakoff calls an "overlord" of the city’s schools (the state seized control of the chronically struggling and corruption-ridden district in 1995). The other is Newark’s then-mayor Democrat Cory Booker, a “gregarious and charismatic…honors student” boasting a “golden résumé.”

That’s one hell of a starting point. It’s the sort of opportunity that would have most urban districts salivating. Zuckerberg, Christie, and Booker certainly saw it as a chance to develop a model for other struggling urban school systems to follow.

And yet, five years after Newark’s chance carpe diem moment, the reform efforts have generated far more heat than light. Russakoff’s book, built out of reporting she published last year in the New Yorker, tells the tale of how a variety of actors managed to spin Zuckerberg’s gold into straw — and Newark’s best laid plans into controversial chaos. It’s a story of demagoguery, mismanagement, and the ultimate triumph of district dysfunction over well-intended hope.

If you read Russakoff’s account and find your beliefs vindicated, you’re not trying hard enough

Those good intentions matter: “The Prize” is chock-full of culprits who bear some responsibility for converting promise into paralysis, but there are essentially no villains. And while there are some bursts of heroism amidst many, many failures, neither are there winners. The reformers' clumsy efforts at "transformational change" tarnishes them and their ideas — and leaves the city's education politics poisoned. Their opponents blunt many of the efforts to change the school system, but their political venom leaves Newark’s deplorable educational status quo largely in place.

It’s tempting to see Newark as conclusive proof that education reform is fatally flawed, or that its opponents are somehow vindicated by the limited changes that Zuckerberg’s $100 million produces. But “The Prize” is much more sophisticated than that lazy, ideologically-comfortable, read.

No. This is a story where more or less everyone in Newark loses. There is no easy solution to the city’s deep and persistent troubles. So in addition to the many culprits, “The Prize” is also — appropriately — packed with caveats: Sure, Newark’s school district is a dysfunctional embarrassment, but changing it dramatically ignites huge pushback. But slow progress is leaving kids stuck. But fast progress bothers lots of community stakeholders. But community stakeholders want schools to get better quickly. But they don’t like those leading the effort. And so on.

Here’s just one example: Russakoff closes one of her chapters with district staff agog that the new district leadership got its students enrolled before the first day of school. According to Russakoff, that basic task annually overwhelmed the Newark school district; it was usually weeks into the school year before schools could start to get vaguely stable information about their enrollments.

The very next chapter opens with worries about how the drive to streamline district resources and expand high-quality charter schools might disrupt longstanding relationships between teachers and communities. Many of these schools are comprehensive failures: They fail students in the classroom and they fail at basic organizational tasks (like on-time enrollment).

There’s a tension here: either the reformers are going to be allowed to build an effective system, even when it’s painful, or they’re not. Yes — reforms are disruptive. Systemic dysfunction needs disrupting. “The Prize” is shot through with these sorts of tradeoffs. So if you read Russakoff’s account and find your beliefs vindicated, you’re not trying hard enough.

Russakoff is unsparing in her treatment of the district’s persistent, comprehensive failures. Even though Newark’s district schools receive around $20,000 per student (e.g. more than double what California spends), she finds campus after campus where resources seem to be in short supply.

Why? “District money,” Russakoff writes, “gushed and oozed in myriad directions.” For instance, the district “spent $1,200 a year per student on…janitorial services.” This was triple the market rate; a hard-charging Teach For America (TFA) alumnus calculates that the gap between these numbers “could have paid salaries for up to ten additional teachers and counselors” at his district school. There are countless other examples of the district’s cost overheads preventing resources from supporting quality instruction in classrooms.

The consequences of this dysfunction are awful. Russakoff explores several decaying district schools which serve Newark’s poorest, most at-risk students. The district used one, she writes, “as a dumping ground for teachers no other principal wanted.” Newark’s district schools are often, she says, the city’s “employer of last resort.” These schools enroll students based on real estate — the surrounding neighborhoods — so their enrollment is often hyper-segregated and constantly fluctuating because of housing instability resulting from prolonged urban poverty. Their budgets are correspondingly unpredictable.

What does this prove? That the reformers’ failed efforts to revamp the district were somehow misguided or malevolent? That Newark’s normal operating procedure — hemorrhaging resources at the district before sending the leftovers to schools — was somehow worthy of preservation? Ridiculous.

There are outstanding district teachers working heroically in these conditions. Teach For America alumni Princess Williams, Charity Haygood, and Dominique Lee loom particularly large. But their work faces constant headwinds. They ask the district to allow them flexibility to redesign and turn around one of its failing schools, only to have core elements of their strategy — a focus on the early grades and authority to pick their staff — rebuffed.

Against that backdrop, Newark’s high-performing public charter schools provide an uncomfortable point of comparison. Leaders at the Knowledge is Power Program’s Spark Academy had broad latitude to build their schools’ staff and core teaching model in a way that supported low-income students. Sure, Spark received less in per-pupil funding than the district’s schools, but it still managed to get more money to classrooms — to students — because it isn’t saddled with the district’s considerable overhead costs. Guess what? Newark charter schools considerably outperform the district.

The district’s dysfunction wasn’t a secret to Zuckerberg, of course. His largesse was supposed to support the district’s schools while also empowering leadership to clean up the system. So state-appointed Newark Superintendent Cami Anderson and her colleagues take on the challenge of spending the money to make order of the district’s chaos. She charges directly at problems with all the subtlety of a steamroller — Russakoff terms it “gale-force advocacy.”

But several of her reforms spark such strong community pushback that she’s soon harassed by a group Russakoff characterizes as “a cadre of hecklers who came to almost every public forum to inveigh against Christie, Booker, and purported conspiracies.” After being shouted off a number of Newark (and Washington, D.C.) stages, Anderson gives up on engaging the community. This predictably fed the hecklers’ narrative — that Anderson was secretive and served masters other than the district’s children (So did revelations that the district was contracting with some consultants to the tune of $1,000 per day). But driving Anderson out of the public square didn’t improve the district’s schools; it paralyzed Newark’s ability to manage school operations.

As the book closes, Christie is campaigning for president, Zuckerberg’s money is nearly spent, Booker is gone, and Anderson’s opponents have coalesced around victorious mayoral candidate (and high school principal) Ras Baraka. Anderson didn’t last much longer.

Urban education reform is messy, difficult work. It’s often painful. It would be nice if there were a way to have dramatic improvements in long-ignored, under-resourced schools without upheaval. It would be nice if intractable problems like achievement gaps between wealthy and poor or white and African-American students could be tidily collaborated away. But that’s not how big, tough problems work.

There’s an old, semi-famous quote from German political philosopher Max Weber: “Politics is a strong and slow boring of hard boards. It requires passion as well as perspective.” That is, change comes as a product of big, audacious dreams and the punishing, unglamorous work of grinding through to make them real. It comes from the combination of big new resources and from their strategic use.

What are we to make of Russakoff’s book and Newark’s example? Some will no doubt finish, set it down, and lower their hopes. We might conclude that blue ribbon commissions and marginal, inoffensive regulatory tweaks make better education policy…simply because they’re politically easier. Or we might decide to ignore dangerous and wildly ineffective schools until we’ve lowered child poverty rates across the country. Or we might conclude that urban school districts are doomed to failure, that no amount of money and creativity can overcome their substantial governance limitations.

Or instead, we might finish the book, brace ourselves, and accept that there are no pain-free shortcuts to big improvements in educational equity. That is, we might resolve to work harder on behalf of underserved students — but armed with a fuller understanding of the degree of difficulty. I think this is the approximately right attitude. Reform work will be hard and it will be unfulfilling for years. It will involve complicated tradeoffs and lots of mistakes. But dammit, that’s just how politics works.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)