Report: Training of Ohio Teachers in the ‘Science of Reading’ Earns Mixed Grades

Amid the governor’s push to change how reading is taught, a new analysis surveys 26 public and private Ohio teacher training programs.

Get stories like this delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

As Ohio governor Mike DeWine moves to require schools to use only the science of reading, a new analysis has found the state’s teacher training programs are uneven in preparing prospective educators to use the phonics-based approach.

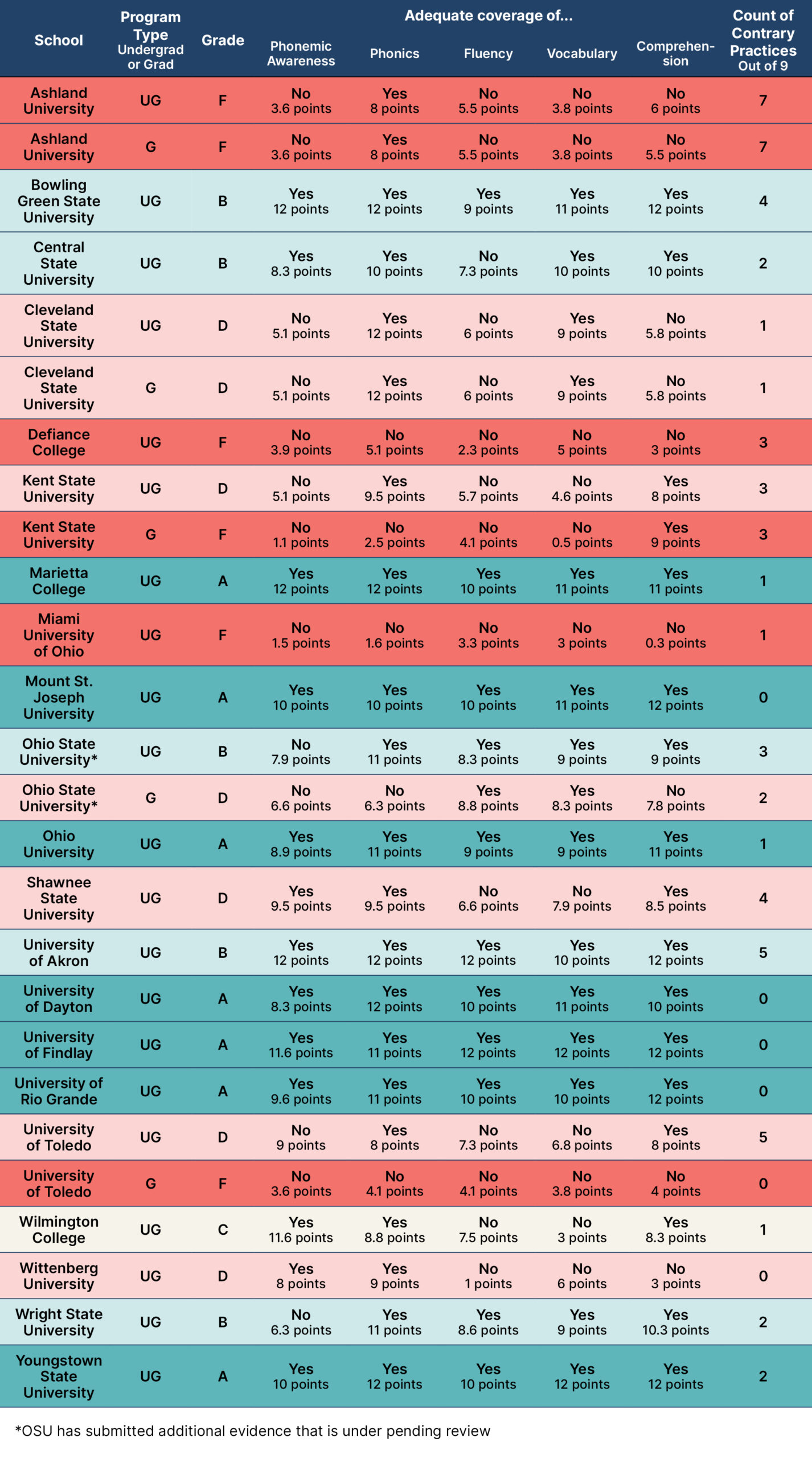

In an evaluation of 26 public and private Ohio teacher training programs by the National Council on Teacher Quality released today, seven received A grades for instructing new educators in how to use the science of reading with young students, while six received Fs.

The report offers some encouraging news for DeWine who wants to ban other literacy approaches that have lost credibility: Colleges are teaching phonics — a key part of the science of reading — to teacher trainees.

But just nine of the 26 programs fully covered all five parts of the science of reading — phonemic awareness, fluency, vocabulary, and reading comprehension, along with phonics. In addition, most did not give new teachers enough practice with students.

“The review yields mixed results, with some programs providing strong coverage of reading science and others barely scratching the surface (or worse, actually teaching candidates bad stuff),” the report concluded.

Colleges are also training prospective teachers in strategies that many consider outdated or damaging, the study found.

“When teachers use these methods, it takes valuable time away from scientifically-based reading instruction, the best methods for children to efficiently and effectively learn to read,” said Shannon Holston, author of the report.

How well Ohio’s colleges are teaching science of reading is a big factor in whether, and how fast, DeWine can succeed in his plan to ban other reading approaches by the fall of 2024; or if the state will have to spend years retraining teachers.

Though the state will likely start tracking what colleges teach soon, it does not now, so the NCTQ analysis offers an advanced insight.

“It doesn’t make sense to shift elementary schools to science of reading, but not address teacher preparation,” said Aaron Churchill, the Ohio research director of the Fordham Institute, which partnered with NCTQ on the study. “Future teachers will struggle and need expensive retraining when they are expected to teach reading consistent with the science.”

The Ohio analysis is part of a larger report coming from NCTQ in June on teacher training in reading across the country. Ohio results were released early at the request of the Fordham Institute, which is active in Ohio education advocacy and helped create NCTQ in 2000. Reports from NCTQ have often been controversial and critical of teacher training programs overall.

One surprise finding: “Three-cueing,” a strategy that DeWine and legislators in other states have singled out to ban from elementary schools, is not commonly taught to new teachers. That strategy, which has students guess at words from pictures or context clues, is part of the popular whole language and balanced literacy lessons used in many elementary schools.

Only three of the 26 rated programs — the University of Akron and Ashland University’s undergraduate and graduate programs — teach new teachers to use cueing with students, Holston said.

The report graded each teacher training program in the science of reading instruction by reviewing course descriptions and syllabi to see what classes cover. They did not observe classes.

The review gave seven Ohio programs overall A’s: Marietta College, Mount St. Joseph University, Ohio University, University of Dayton, University of Findlay, University of Rio Grande, and Youngstown State University.

Six programs were given F grades: Ashland University (undergraduate and graduate programs), Defiance College, Kent State University, Miami University, and the University of Toledo.

Ohio State University, the state’s largest university, scored well, earning a B grade overall.

The 74 is sharing the findings immediately as the Ohio Senate weighs DeWine’s proposal. Universities have not yet had a chance to respond to the report, but The 74 plans to provide additional coverage soon.

The Ohio analysis is part of a larger report coming from NCTQ in June on teacher training in reading across the country. Ohio results were released early at the request of the Fordham Institute, which is active in Ohio education advocacy and helped create NCTQ in 2000. Reports from NCTQ have often been controversial and critical of teacher training programs overall, not just on this specific issue.

Don Pope-Davis, dean of Ohio State University’s College of Education and Human Ecology, has previously said his school, the largest in Ohio, prepares students well in the core skills of teaching reading, including phonics. In a letter to the legislature in March, he said that 96 percent of his graduates in the last three years have passed the state’s teacher licensing test in reading knowledge.

“Our teachers perform at that level year after year because they are well-prepared to teach reading,” Pope-Davis wrote.

“What we teach at Ohio State is in no way at odds with the administration’s proposal.”

At the same time, Pope-Davis joined the Ohio Education Association and Ohio Federation of Teachers, the state’s two large teachers unions, in warning against banning any strategies that could help different students.

“No single commercial program is appropriate for all students, just as no single tool is the only implement for a given task,” he wrote. “We would urge caution with any legislation that prescriptively adopts one approach without any consideration for the individual student.”

Though DeWine, like other Republican officials in other states, is seeking to ban three-cueing, the NCTQ report did not find that it was a major part of teacher training in the state. Out of nine practices that NCTQ considers contrary to the science of reading, the most common ones taught to prospective teachers in Ohio, according to Holtson, are “guided reading,” “running records” and “miscue analysis.”

Though three-cueing is not prevalent in teacher training programs, Aaron Churchill, Fordham’s Ohio research director, said he still wants that strategy banned. School boards are still buying lessons that use it, he said, and veteran teachers who graduated years ago are using it in whole language and balanced literacy instruction.

“If Ohio reforms teacher-prep but does nothing in K-12, we’ll end up with well-prepared teachers in science of reading who end up conforming instruction to what their school is doing,” Churchill said.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)