Report: Teacher shortages don’t exist everywhere, but here are five solutions for where they do

The often-described “teacher shortage” may not be as widespread as commonly thought, but there are places and subjects where teachers are hard to find, and a new report puts forth some fairly straightforward solutions for that.

The analysis, published through the Hamilton Project at the Brookings Institution, wades into the much-argued question of whether teacher shortages are real and what should be done about them.

News reports of shortages have spiked recently, with some policymakers and researchers arguing that schools are struggling to fill vacancies with qualified, effective teachers. A 2015 New York Times headline declared, “Teacher Shortages Spur a Nationwide Hiring Scramble (Credentials Optional).”

The latest analysis reiterates a common response to such claims: that shortages are not an across-the-board or national issue, but a much more targeted problem. The difficulty of recruiting and retaining teachers likely varies by state, by school type, by grade, and by subject.

“Challenges in hiring teachers are indeed becoming more acute,” the paper argues. “But we also stress that these challenges appear to be concentrated in specific high-need subjects such as special education and STEM … and in hard-to-staff schools.”

The report, written by Stanford University’s Tom Dee and the University of Washington’s Dan Goldhaber, discusses a few specific states. In California, for instance, the number of teachers hired without a traditional certification has tripled in recent years, with a large number of those in special education and STEM.

Still, the authors point out that this spike accounts for only a small share of the approximately 300,000 public school teachers in California. New York has also seen a sharp rise in teachers lacking subject-specific certification, though Missouri, for example, has not.

On the other hand, the report suggests that genuine shortages exist in certain contexts — particularly in science, math, and special education, in high-poverty schools, and to some extent, in urban and rural areas.

Based on these data, the analysis suggests several solutions, arguing that “policy efforts that are not targeted toward where … shortages actually exist are likely to be unnecessarily costly and relatively ineffectual.”

Here are five that do:

Pay (some) teachers more

From an economic perspective, the most straightforward way to address shortages would be to raise teacher salaries in areas where they exist. That’s what Dee and Goldhaber recommend: providing “targeted financial incentives” to teachers in “high-need subjects and hard-to-staff schools.”

They point to research showing that even relatively small bonuses can increase teacher retention. For example, a North Carolina study found that an annual bonus of approximately $2,000 for math, science, and special education teachers in high-poverty schools reduced turnover by about 17 percent.

In contrast, the report argues, across-the-board pay raises are less efficient because they don’t zero in on the positions where schools most need to attract candidates.

General salary increases may have other beneficial effects on teacher quality, such as improving recruitment and retention. One recent analysis found that teachers were paid significantly less than similarly educated professionals. In Oklahoma, many teachers must wait well over a decade to make more than $40,000 annually. Perhaps not coincidentally, the state has faced teacher shortages, but a 2016 ballot initiative to increase the sales tax to pay for a $5,000 teacher pay raise was heartily rejected by voters.

Tell teacher candidates which positions are in greater demand

The report suggests a simple way to get prospective teachers to move into shortage fields: make clear what positions have greater job prospects.

In Washington state, for instance, those with credentials in special education and STEM are 10 to 12 percentage points more likely to have a job in the state’s public schools than those certified in elementary education. In other words, obtaining a teaching degree in higher-demand fields, unsurprisingly, offers significantly better employment prospects.

It’s not clear whether teachers lack this information, but the authors suggest communicating it directly to teachers while they are in training through their teacher preparation programs.

Improve recruiting practices

“We believe school districts can and should do more to recruit broadly, aggressively, and in a targeted manner that reflects their particular needs,” the report says. “This could entail increased school district advertising and recruitment out of state, or the formation of partnerships between school district and teacher education programs that cross state boundaries.”

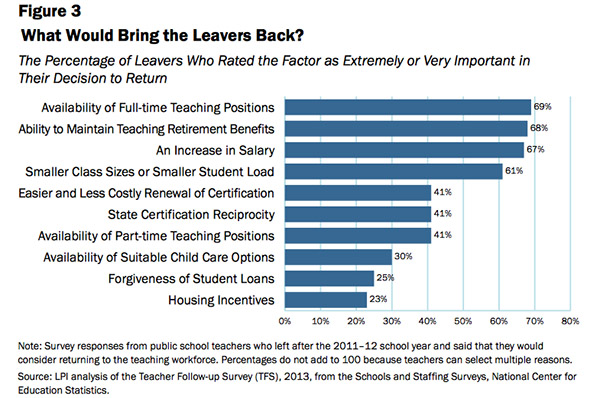

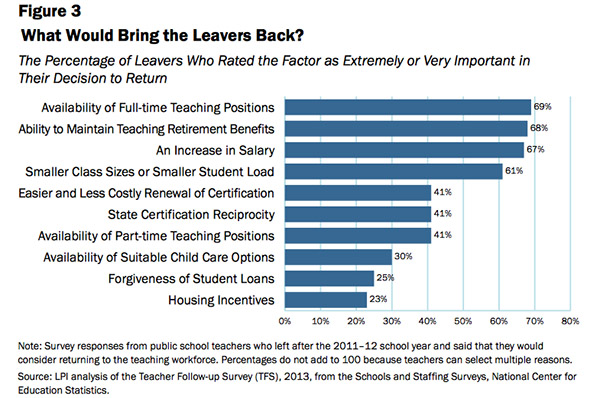

The authors point out that in most years, there are hundreds of thousands of college graduates who obtain a teaching degree but don’t end up teaching. This suggests there are many people out there who could be brought back into the classroom.

While acknowledging that many of those people may not have an interest in teaching at this point, the authors say that “there are ample opportunities for school systems to recruit individuals from other occupations and activities who already have the necessary credentials to teach.”

Make it easier to get certified between states

One reason that some people with backgrounds or degrees in teaching are no longer in the classroom might be onerous certification requirements when moving between states. As The 74 has reported, many teachers switching states find the licensure process difficult, and teacher mobility between states is surprisingly low, according to some studies.

One survey of teachers who had quit but were considering going back found that 41 percent said certification reciprocity between states would increase the likelihood that they would return to teaching.

Source: Learning Policy Institute

Dee and Goldhaber argue that making it easier for out-of-state teachers to get certified would be a low-cost way to expand the pool of potential teachers.

Make it easier to get certified, period

The report states, “We propose that states develop and make more extensive use of alternative licensure programs, particularly for teacher candidates being prepared in high-needs areas, such as STEM fields and special education.”

The authors argue that certification rules can serve as a significant barrier to entry and are not strong predictors of effectiveness, so providing alternative routes that reduce the length of required training may help ease shortages.

One study found that students from selective colleges were much less likely to pursue teaching in states with greater entry requirements.

In other respects, though, allowing an influx of alternative teachers could backfire, as their attrition rates are relatively high, which could exacerbate shortages in the long run.

But Dee and Goldhaber point out that schools may not have the luxury to pick their ideal candidate: “In some cases, the relevant alternative that schools face is not a conventionally and an alternatively licensed teacher; rather, the choice is between an alternatively licensed teacher and a long-term substitute.”

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)