RAND Corp Says 321,000 Undocumented Children Entered U.S. Schools From 2016-2019, Sparking Need for More Teachers, Training and Funding

Help fund stories like this. Donate now!

RAND Corp. researchers estimate 321,000 undocumented and asylum-seeking children enrolled in the nation’s public schools between late 2016 and 2019, just ahead of the more recent and dramatic uptick in newcomers from Central America, Mexico, Afghanistan and Haiti.

The new report, derived from numerous sources that track immigration, details these students’ challenges and their impact on districts. Their number, difficult to ascertain on a national basis, represents a fraction of the 491,000 children under age 18 who arrived at the southern border in that same time period and remained in the country with unresolved immigration status in early 2020, according to RAND. The youngest among them were ineligible for school while some of the oldest never enrolled.

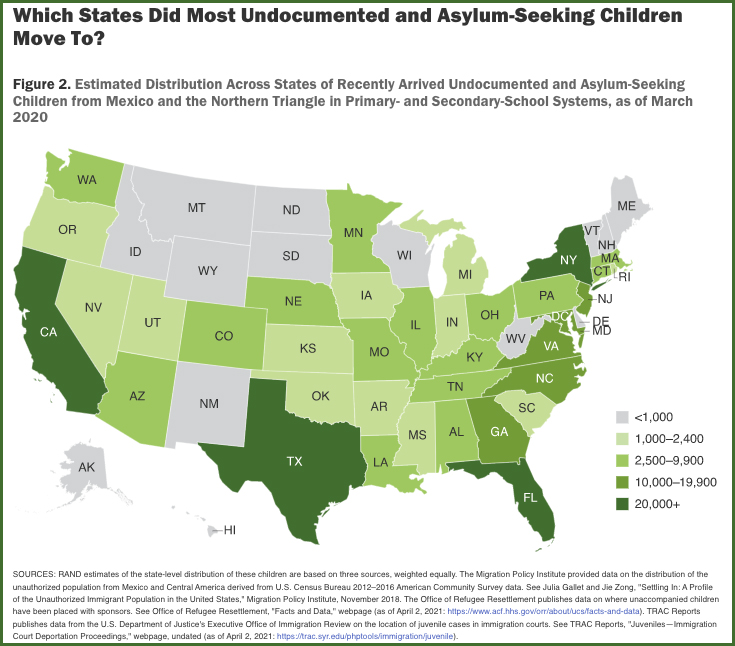

Roughly 75 percent of the children in the RAND study landed in just 10 states, including California, Texas, Florida, New York and Louisiana. Their arrival prompted the need for additional hires: RAND calculated that seven states would need at least 2,000 more teachers and other personnel to maintain student-staff ratios.

The need was even more acute in Los Angeles County and Harris County, Texas, which includes Houston: Each would need 1,000 additional educators, the organization concluded.

RAND researchers said they decided to study this population in part because their numbers have grown in recent years—and because their challenges are unique.

“Their needs are fundamentally different from those of many other immigrant children, and they are part of the future of the United States,” said senior policy researcher Shelly Culbertson. “They also have resilience and hopes and dreams—and by federal law they have a right to a public education.”

Despite a landmark Supreme Court decision in 1982 that prohibited discrimination against students based on their immigration status, many young newcomers have been unlawfully turned away or shunted into inferior programs by school administrators who fear they will not graduate.

Oliver Torres, senior outreach paralegal at the Southern Poverty Law Center, an organization that has fought for the educational rights of newcomer children, said anti-immigration laws proposed and enacted across the country in recent years have had a chilling effect on many families, discouraging their participation in all elements of public life, including school.

Torres, a former English as a second language teacher, said new immigrants are so focused on simply reuniting with their loved ones — especially in the case of children separated from their parents at the border — that education has become less of a priority, a phenomenon he called “heartbreaking.”

Looking back to the years covered in the RAND study, he recalled the case of a 17-year-old boy from Guatemala held for more than six months at the controversial Homestead detention center for migrant children in Florida. The teen, who was only allowed outside for one hour a day, said he was pressured by staff to take medication to quell the emotional outbursts he suffered after being repeatedly told he would be reunited with his father only to see that promise broken. By the time of his release, the boy was too distressed to tend to his education.

“The idea of going to a two-hour night school class for English a couple of times a week seemed overwhelming,” Torres said. “It was such a level of trauma, that it was clearly going to take a significant amount of time to heal. All he wanted was just not to cry every day.”

Two districts serving new arrivals well

The teen’s experience echoed that of many undocumented children who have fanned out across the country in recent years. RAND, in addition to its nationwide view, also homes in on Jefferson Parish Schools in Louisiana and Oakland Unified School District in California, both of which have served these children for years. It lauded each for their admissions processes and for the academic support their immigrant students receive, including referrals for outside assistance.

RAND also praised the districts’ efforts to address students’ social-emotional needs, but administrators from both point to numerous ongoing challenges even prior to the pandemic, which caused a massive drop in enrollment among newly arrived students.

Veronica Garcia-Montejano, principal at Oakland International High School, a campus designed for newcomers, said her concerns for her students expand well beyond academic goals to their fundamental needs, including food and housing. Many are transient, moving between family, friends or the foster care system.

“They have a huge hurdle to overcome in developing that relationship with the person who is caring for them,” she said. “And if you are not an unaccompanied minor but haven’t seen your parent in years, you are in the same situation.”

Many newcomers are pulled into the workforce to manage financial obligations: Some have to pay back the smugglers who brought them to America, send remittances home, support themselves and contribute to their household, Garcia-Montejano said.

Her current students include two brothers, ages 16 and 18, living on their own. They have to balance their studies with earning enough money to pay rent.

“They are all they have,” she said.

During COVID-19, some students have qualified for rent relief but others have less formal agreements and are unable to seek official help, Garcia-Montejano said.

“We all have to assume the students are coming to the classroom with complex trauma, which presents itself in many ways, from overstimulation to withdrawal,” she said. “The most important thing for the adults in the building to do is to begin developing positive relationships with these students.”

Deborah Dantin, principal of Alice Birney Elementary School in Metairie, Louisiana, part of Jefferson Parish Schools, said one of her biggest struggles is in communicating with parents who do not speak English. Roughly 90 percent of her newcomer students and their families speak Spanish.

“We have lots of people on campus who speak Spanish, but it’s not the same as a direct call with a teacher or principal,” Dantin said. “We have someone translating, but it’s complicated, confusing and long.”

The communication barrier extends to the students themselves. Dantin would love to have a Spanish-speaking educator inside every classroom but until then, her school must employ other means to serve these children: Teachers sometimes use supplemental materials in Spanish to give students the support they need to make the leap to English.

And her school also offers dual-language classes for native English speakers and newcomers in younger grades. The offering helps Spanish-speakers read and write in their native tongue, a skill that will help them learn English because literacy is a transferable skill.

‘Don’t think of us as aliens’

Sua Ramos, a 17-year-old senior at Oakland International High School, remembers those early days trying to adapt to a new culture. Ramos, who identifies as non-binary, fled Honduras with their family after sixth grade rather than risk injury or death because of gang-related shootouts, common in their community. It was a difficult transition: they left friends and family behind and could barely utter a word in English.

“It was like I was on a different planet,” Sua said. “I didn’t know what the teacher was teaching. I was so confused. But as I got to know people, they helped me. I learned English little by little.”

RAND, in an extensive, expensive wish list, recommends the federal government improve the tracking of these students and create a records-sharing agreement with the Northern Triangle countries of Guatemala, El Salvador and Honduras similar to the one already in place with Mexico.

It says schools should work closely with local resettlement groups, federal and state agencies to help families access social, medical and legal services — and that the federal government should provide schools with additional funding for these students on a rolling basis as the money often lags their arrival.

RAND’s estimate includes those children who immigrated to the United States between Oct. 1, 2016 and Sept. 30, 2019 and was derived using data from spring 2020, just prior to the pandemic-related school closures that began in mid-March.

It combined three sources of data to formulate an “informed estimate” of where these children live. The first came from the Migration Policy Institute, which had already examined where earlier groups of immigrants settled throughout the country. The second was the Office of Refugee Resettlement, which kept records on where unaccompanied children were placed with sponsors at the state and county level and the third was Syracuse University’s Transactional Records Access Clearinghouse, which gathers data on immigration proceedings throughout the country, collecting records from the departments of Justice and Homeland Security.

RAND found more than three-quarters of children who arrived with their families were under the age of 12 while 74 percent who came without a parent were between 15 and 17 years old.

Excluded from their study are the thousands of new immigrants who have crossed the border in the years since. Though the flow slowed during the pandemic, it skyrocketed upon news of Biden’s election. Persistent crime, political chaos and ongoing economic catastrophe, sometimes made worse by natural disasters, also played a role.

Some 12,400 Haitians who were part of a massive encampment in Del Rio, Texas, have been admitted to the United States in recent weeks. Their arrival came around the same time that America welcomed thousands of newcomers from the Middle East, a trend that is expected to continue: Biden seeks to bring 95,000 Afghans to the country through 2022.

The president just introduced new rules to secure protections for undocumented people brought to the United States as children and plans to admit 125,000 refugees next year, a figure that will no doubt include a sizable number of school-aged newcomers.

Ramos, the 17-year-old student from Oakland, hopes native-born Americans will reconsider old prejudices about the new arrivals.

“I’d ask them to be patient with us,” they said. “It’s not like we are dumb or something. It’s just there’s a language barrier. Give us a chance. Don’t think of us as aliens. We are people just like them who want a better life.”

Help fund stories like this. Donate now!

;)