Race & Class: Chicago Schools Sue State, Claim Minority Kids See 78 Cents Per Dollar Sent to White Schools

Chicago Public Schools is in trouble. Facing a massive budget shortfall that’s already prompted millions in cuts — and that could force schools to close weeks early this spring — officials are looking to a county court for a lifeline.

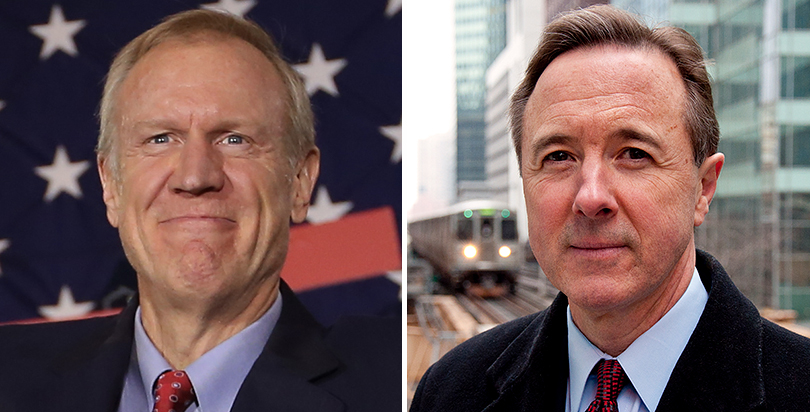

District CEO Forrest Claypool has asked the Cook County Circuit Court to move swiftly in resolving a CPS lawsuit in order to avoid “imminent and irreparable harm” to the city’s students. The gathering crisis, Claypool argues, was precipitated by Gov. Bruce Rauner’s veto of legislation in December that directed $215 million in pension relief to the district.

Chicago’s situation is dire, but its use of a lawsuit to fend off a school funding emergency is increasingly commonplace. Facing unprecedented budget shortfalls, cities and districts — which usually lack the tax base of nearby suburbs — are asking judges to lead the way in establishing more equitable state funding, often with success. In Connecticut, for example, a far-reaching court decision last year ordered the state to develop a funding formula that directs a fair share of resources to schools in low-income communities. The Kansas Supreme Court reached a similar conclusion earlier this month.

Chicago’s effort resembles those of other education plaintiffs — but there’s a difference. Rather than focusing on education law and constitutional protections — in what are known as “adequacy” lawsuits — CPS has filed a civil rights complaint: It contends that Illinois’s “discriminatory education funding scheme” especially hurts minority students.

According to the February lawsuit, Chicago students — who are predominantly black and Hispanic — receive fewer state resources than the predominantly white school districts in the rest of the state. The Illinois Civil Rights Act of 2003 prohibits policies that fall disproportionately on members of particular racial groups.

Rauner said earlier this month he was willing to give CPS the $215 million if state lawmakers approved legislation to reform the state’s pension system as part of a larger proposal.

In an interview with The 74, Claypool said Chicago’s case is more straightforward than most adequacy lawsuits. The district argues that the state began to provide education funding in a racially discriminatory manner in 2012, when spending on CPS fell below 20 percent of the state’s total education dollars.

“The crisis has developed quickly, it’s developed over a five-year period, it’s accelerating and will get worse,” Claypool said. “Because of the way the system is now set up and the way it has been executed and practiced, our kids are getting 78 cents for every dollar that children in the rest of predominantly white Illinois receive, and our children are 85 percent poverty and 90 percent of color.”

Indeed, a recent report shows that, year after year, Chicago is among the most fiscally deprived urban districts in the country. Nationally, analyses show that high-minority schools receive significantly less money than whiter districts. While the conversation about education-funding equity (unlike student achievement) usually centers on income — high-poverty school districts generally receive fewer education dollars than their more affluent counterparts — a similar gap also exists based on racial groups.

Although the CPS complaint does not focus on adequacy, Claypool said its argument is straightforward: “If the state is going to fund education — we’re not arguing that they do or don’t — but if the state chooses to fund education, whether it’s a dollar or a trillion dollars, under the Illinois civil rights statute, they cannot fund schools in a racially discriminatory manner,” he said.

Adequacy lawsuits have been waged over the years in Illinois, but courts have typically referred education funding issues to the legislature, said Mike Jacoby, executive director of the Illinois Association of School Business Officials. Though the state constitution calls for a high-quality education, equitable education is an aim, a “fundamental goal,” not something that must be achieved for funding to be considered lawful.

Chicago shortchanged

Chicago’s woes run decades deep, including years of missed pension payments, recurring battles between city hall and one of the nation’s most militant teachers unions, and an acrimonious relationship between city and state lawmakers. Despite all the disagreements, almost everybody concurs, however: The state’s education-funding formula is broken.

Illinois contributes only about 25 percent of the funds that support schools; the national average for states is closer to 50 percent. That means districts must derive most of their funding through local property taxes, which can vary widely between poor and wealthy communities.

While Chicago enrolls about 20 percent of the state’s total public school population, it receives only about 15 percent of the total education dollars (including pension costs), according to the CPS complaint. Children of color make up 90 percent of the district’s total student population, compared with 42 percent in the state school districts excluding Chicago.

(The 74: Chicago Public Schools 101: The Politics, Passion, and Hopeless Financials Behind a System in Crisis)

Crippled by large pension liabilities, inadequate state funding, local funding constrained by low property tax values, and declining enrollment, the school district began to scramble in December after Gov. Rauner vetoed the legislation sending $215 million.

While the state has historically given Chicago little aid to pay for the district’s ballooning pension costs, Rauner’s veto plays a key role in the CPS lawsuit. The governor’s office and the Illinois State Board of Education are both named in the complaint, and Claypool calls Rauner’s veto “destructive.” If the judge does not act in time, he says the school year could end 20 days early.

“In the absence of equal funding from the state or judicial relief or the legislature coming through belatedly, our district faces a decision between insolvency or cutting classrooms and teachers or shortening the school year or doing a series of things that have a significant negative impact on the education of children,” Claypool said. “That is imminent, that is months away, and it is irreparable once it occurs.”

Both Rauner and the state education board declined to comment on the pending legislation.

A week after CPS filed its complaint, the Chicago Urban League reached a settlement in a case spanning nearly a decade that alleged that the state’s education finance system discriminated against minority students. Limited in scope, the settlement prevents Springfield from implementing across-the-board cuts to districts statewide when money is tight; state administrators must now factor in a district’s ability to sacrifice the funds.

And while Jacoby said CPS likely would have an uphill battle with a judge to prove that the state intended to discriminate against a protected class, Claypool argued it shouldn’t have to.

“What matters is what’s called disparate impact,” he said. “If the official government action has a negative disparate impact on minorities, then it is unlawful.”

Acknowledging that CPS is underfunded, Jacoby was skeptical about the district’s legal strategy. “I think all students are being ill-served through the formula and not just specific classes of students,” he said.

Also among the school district lawsuit’s critics is Karen Lewis, president of the Chicago Teachers Union, who called the legal action a “cynical political ploy” to divert attention from local attempts to fix the district’s money woes. Teachers could strike in May if the district chooses to close its doors early for the school year.

“The mayor behaving as if he has zero solutions is incredibly irresponsible,” Lewis said in a news release. “Rahm wants us to let him off the hook for under-funding our schools and instead wait for the Bad Bargain to pass the Senate or Rauner’s cold, cold heart to melt and provide fair funds.”

A national scale

While conversations about funding disparities generally focus on income, a report by the advocacy group The Education Trust found that racial gaps were even more severe.

On a national basis, school districts with the highest proportion of low-income students receive about 10 percent less per student in state and local funding than the lowest-poverty districts, according to a 2015 report by the group. Illinois had the largest disparity, allocating about 20 percent less state and local money to the poorest districts.

And while race and class often overlap, districts serving the most students of color received about 15 percent less money per student than those serving the fewest minority students, according to the report. Natasha Ushomirsky, The Education Trust’s director of K-12 policy development, said education policy experts are more accustomed to looking at inequalities in education funding based on levels of poverty than race.

“I think the issue of disparities based on concentrations of students of color are something that just hasn’t gotten nearly as much attention as disparities based on poverty,” she said, referring to school funding. “That may be one area where people may not quite realize to what extent those disparities exist. It’s something we have to continue to shine a light on.”

In Pennsylvania, where lawmakers also have been grappling for years to fix an inequitable funding system that advocates say shortchanges students in Philadelphia and other areas with large populations of low-income children, data scientist David Mosenkis discovered a disturbing trend.

In a series of reports for the faith-based advocacy group POWER, Mosenkis looked at the state funding levels at all 500 school districts and compared them according to student income and demographics. Even when comparing districts with similar student populations economically, he found that schools with higher concentrations of students of color were getting systematically less money than whiter districts.

“The racial disparity exists not only at the very poor end of the economic spectrum but all along the economic spectrum,” said Mosenkis. “I expected there was going to be this systemic bias against the poorest, blackest districts, but I was surprised to see that even districts that have 60 or 70 percent white students, if you get just another 5 or 10 percent white students you get higher funding.”

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)