Reality Check: Are the Education Changes Demanded By Connecticut Judge Even Possible?

“Sweeping,” “far-reaching,” “radical” — so said media accounts of the Connecticut court decision giving the state 180 days to propose several changes to its education policies.

The ruling called for a major revamping of teacher pay and evaluation, school funding, high school graduation standards and special education.

The state attorney general has promised to appeal the decision, emphasizing the scope of the ruling. “This decision would wrest educational policy from the representative branches of state government, limit public education for some students with special needs, create additional municipal mandates concerning graduation and other standards, and alter the basic terms of educators’ employment — and entrust all of those matters to the discretion of a single, unelected judge,” said Attorney General George Jepsen in a statement.

In addition to its breadth, Judge Thomas Moukawsher’s ruling is notable for the fact that, on some issues, it suggests implementing policies that, few, if any states have adopted.

Graduation exams may do more harm than good

“The facts are incontestable,” the judge wrote. “Test scores show that high schools in impoverished cities are graduating high percentages of students without the basic literacy and numeracy skills the schools promise.”

Moukawsher’s ruling pointed out that even a witness for the state agreed that Connecticut’s “high schools are graduating students unprepared for higher education.”

He suggests an “obvious” solution: “use a readily available means to show that students have been educated … some form of objective test.”

What the ruling does not discuss is the fact that, as The 74 previously reported, no state in the country has implemented graduation requirements aligned with Common Core’s college and career readiness standards. This is perhaps not surprising, since raising the bar that high would dramatically reduce the high school graduation rate.

The decision does not specifically mandate such an exam but strongly suggests doing so. Connecticut would be the first state to institute such a stringent requirement.

Stanford professor William Koski told The 74 he is wary of this approach. “High-stakes testing and holding kids accountable when the state itself ought to be held accountable for providing the resources and the opportunities to learn for these kids — that’s not something I can get behind.”

Indeed, several research studies show that high school exit exams have few positive effects and several negative effects on student outcomes and are more likely to increase than reduce inequality in educational outcomes.

Teacher eval and compensation reform: It’s complicated

Because Connecticut’s teacher evaluation system gives 98 percent of teachers high evaluation scores, Judge Moukawsher described it as “uselessly perfect.”

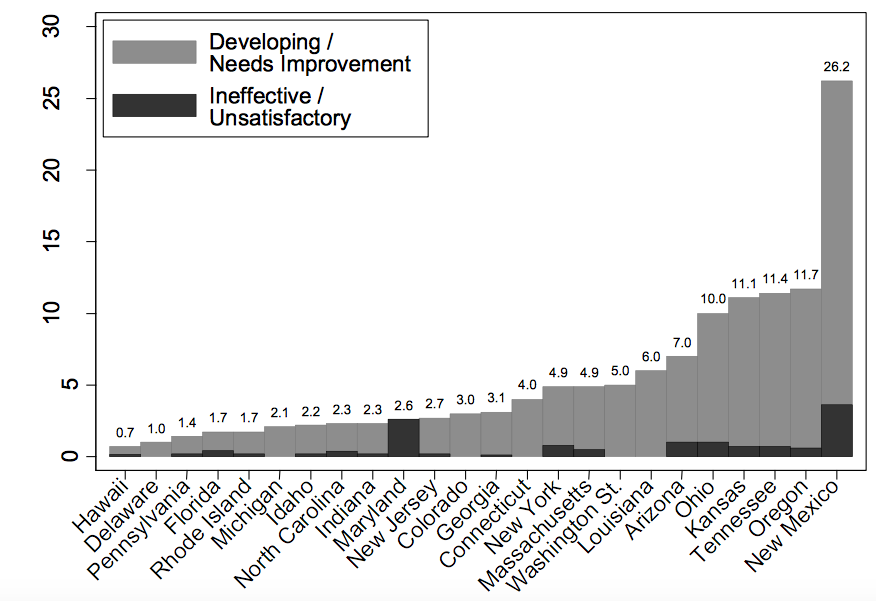

Here, too, Connecticut’s current policy is the rule rather than the exception. A recent study found that even under new evaluation systems supported by the Obama administration, the vast majority of teachers receive high marks. Among 19 states examined in the study, most gave upwards of 95 percent of teachers strong ratings; only one state had more than 12 percent of its teaching force receive subpar scores.

That state, New Mexico, is in the midst of a lawsuit about its evaluation system, with a judge ordering the state not to make any high-stakes decisions based on teachers’ ratings, pending a trial and decision.

Moukawsher says other states’ failure is not a good enough answer: “The state insists that many schools across the country suffer from this problem, but — as we all learned in school — others doing something wrong is hardly an excuse.”

The judge also criticized the state’s teacher compensation system for failing to connect pay to effectiveness and instead relying on years of experience and degrees held, which are only rough proxies for effectiveness at best.

Data from 2011–2012 show that the vast majority of school districts use a fixed salary schedule, and few pay more money to teachers based on their performance.

If Connecticut implemented a differentiated evaluation and pay system statewide, it would be unique.

But that doesn’t mean the judge is wrong.

University of Maryland professor Jennifer King Rice, who testified at trial for the plaintiffs, said Moukawsher was “absolutely correct” in his diagnosis of teacher evaluation systems. She described teacher evaluation as a long-running problem across the country.

“I think Connecticut is not unusual … but that doesn’t mean that [it] has a good system,” she said. “It means that everybody has a bad system.”

Meanwhile, studies have found that performance-based pay systems generally don’t incentivize teachers to try harder, though they can help keep the most effective teachers in the classroom, leading to gains in student achievement. Extra pay for teachers in shortage areas — those teaching science or math or working in high-poverty schools — can positively affect recruitment and retention. Rigorous teacher evaluation systems can help teachers get better while also replacing less-effective teachers.

“If we’re moving to performance-based pay, conceptually, that’s a very good idea,” said Rice, who has studied performance-based pay systems extensively. “The problem is we don’t have really good measures of performance.”

Both teacher evaluation and performance-based pay systems have been a challenge to implement. For instance, evaluating teachers in non-tested subjects is quite difficult, and teachers often oppose test-based evaluations where they do exist.

Moreover, performance-based pay systems are typically quite complicated to operate, as districts have struggled to communicate to teachers how to qualify for bonuses and ensure the system is fair.

That doesn’t mean performance-based pay and tougher evaluation are not worth the effort, but it does suggest that initiatives in these areas will take time, care and probably money to implement well.

Special education ruling draws sharp rebukes

Advocates for students with learning disabilities were not happy with Moukawsher’s decision pertaining to special education. The ruling described “the problem of spending education money on those in special education who cannot receive any form of elementary and secondary education.”

What precisely the state should do instead wasn’t clear, but the judge suggested Connecticut redirect money from severely disabled students, pointing out that “neither federal law nor educational logic says that schools have to spend fruitlessly on some at the expense of others in need.”

Mimi Corcoran, head of the National Center for Learning Disabilities, called the judge’s decision in this respect “disheartening,” “outdated” and “shocking.”

“It doesn’t align with our society’s moral judgment or our civil rights law,” she said in an interview.

“There is a federal right for these kids to receive a free and appropriate public education at the public’s expense,” said Koski, the Stanford professor, referring to the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act, known as IDEA. “Treating the education money pot as a zero-sum game [where] we rob kids in general education to pay kids in special education is a very divisive and dangerous way to go.”

It’s not clear how Connecticut’s system of spending education dollars compares with other states’ systems. The Houston Chronicle recently reported on extensive efforts by Texas to reduce spending on students with disabilities; this was widely seen as a scandal, likely in violation of IDEA.

Both Koski and Corcoran said they believed that the judge’s ruling, depending on how exactly it was implemented, would likely violate IDEA.

More money, fewer problems

In some ways, Moukawsher’s ruling on funding was the most straightforward and least surprising: In short, he found that because Connecticut had not even used a funding formula in the past few years, it needs to create a new one that ensures that disadvantaged students get their fair share of resources.

Courts in many states have required funding to be more equitably distributed. It hasn’t always been easy — courts and legislatures, such as those in Kansas and Washington recently, often feud. Cases like the Campaign for Fiscal Equity in New York have to be refiled after the state begins to backslide on funding obligations.

Jim Ryan, a legal scholar and dean of the Harvard Graduate School of Education, previously told The 74 that courts can be effective in creating educational change where some political will exists but that “in states where the legislature doesn’t really have an interest in doing what the court wants to do, you see endless delays and countless returns to court.”

In many cases, court rulings have, eventually, led states to spend more money on schools — and once they’ve done so, student outcomes have improved, often significantly, according to recent national studies.

One approach Connecticut could consider is the consolidation of school districts so that poor urban areas are in the same district as surrounding affluent suburbs. Doing so might advance both funding equity and school integration.

Moukawsher said the state didn’t necessarily have to spend more money overall, but the plaintiffs say that any attempt to address the inequities highlighted would require new resources.

Koski agreed that this is key: “Money matters. The evidence based on that is growing. We do need to ensure that that necessary condition is fulfilled, and unless that necessary condition is fulfilled in the Connecticut case, we’re not going to see any meaningful improvement.”

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)