Principled Stand or High-Stakes Standoff? For a Second Year, Houston Thumbs Its Nose at a Popular Texas School Innovation Law and Risks Takeover

Houston, you have a problem.

Unless the board of Texas’s largest school district does an unexpected 180 in the next three weeks, it will set in motion a chain of events that by law will force the state to either close several chronically underperforming schools or take over the entire district.

It’s a toss-up as to which option is more unpalatable, and state and local officials from both political parties have lambasted the Houston Board of Education for refusing to consider any of a number of alternatives that would head off state intervention.

A relatively new state law gives officials just two options when a school has been among the lowest-performing 5 percent in the state for five or more years: close it or take over the board of the district it belongs to. A second law allows a district to forestall those consequences by inviting in an outside partner.

Texas districts have until Feb. 3 to submit proposals to the state for engaging third parties — nonprofits, universities, cities, and nonprofit charter school networks — to help turn around schools at risk of ending up on the list of chronic underperformers. Because the partnerships can mean extra state funding and freedom from red tape, districts throughout Texas are taking advantage of the law not just to protect their most challenged schools but also to start new programs and innovate in stagnant ones.

For example, in tiny Hearne, 90 miles east of Austin, faculty from teacher-training programs are overseeing elementary school reading and math instruction tailored to pupils’ skill levels. At CAST Tech High School in downtown San Antonio, funding and expertise borrowed from a grocery empire are being used to teach cutting-edge technology skills. Galveston offers a high-quality kindergarten-readiness program for 3- and 4-year-olds.

Yet for the second year in a row, a slender majority on the Houston Independent School District’s notoriously fractious board has refused to respond to either the legal carrots or the sticks.

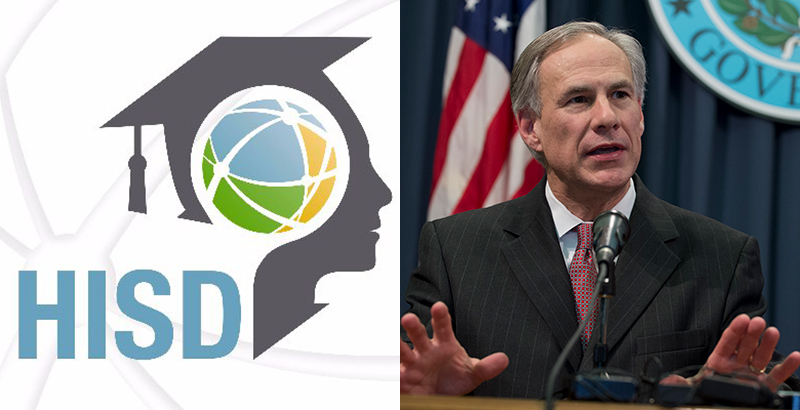

“What a joke,” Texas Gov. Greg Abbott tweeted. “HISD leadership is a disaster. Their self-centered ineptitude has failed the children they are supposed to educate. If ever there was a school board that needs to be taken over and reformed, it’s HISD.”

What a joke. HISD leadership is a disaster. Their self-centered ineptitude has failed the children they are supposed to educate. If ever there was a school board that needs to be taken over and reformed it’s HISD. Their students & parents deserve change. https://t.co/atM45U3Jmr

— Greg Abbott (@GregAbbott_TX) January 3, 2019

It’s the exact showdown Houston-area state Rep. Harold Dutton Jr., the African-American Democrat who pushed for the automatic state intervention law four years ago, feared would be necessary to push past decades of inaction on the part of local school officials. A disproportionate number of the district’s failing schools, populated almost entirely by students of color, were located in his district. It’s a constituency, he has argued, that has long been given short shrift by the board.

“Sure, we can wait on HISD to fix them,” he said, referring to a handful of overwhelmingly impoverished schools that he believes the school board has long neglected. “But I am convinced that without a gun to their head, it won’t happen.”

Forcing the school board to act

In 2015, frustrated that the Houston board shrugged, year after year, at conditions in its lowest-performing schools, Dutton convinced the chair of the House Public Education Committee at the time, Republican Jimmie Don Aycock of Killeen, that it was unfair that students and teachers were held accountable for their performance while school board members were not.

By way of example, Dutton told Aycock about Houston’s Kashmere High School, which has failed to meet state standards for nine years and last year was among the bottom 1 percent in the state. The school board, he opined, has failed to take responsibility for ensuring that Kashmere and other impoverished schools have equitable resources, including high-quality teachers and a stable administration.

“I further explained that Kashmere’s academic rating remains unacceptable because its students always did poorly on the math portion of the standardized test,” he wrote. “I shared that my research uncovered that the students at Kashmere never had the benefit of a certified math teacher in the classroom. And this was not just for one or two years, it was never. Rep. Aycock was astounded. More especially, he asked, how do we fix this?”

Because they are the largest employers in most state House districts, school systems have lots of political influence in Texas. So the law Aycock and Dutton pushed through compels state officials to intervene. The law passed with just a handful of “no” votes.

A second law, passed in 2017, says the consequences can be averted at least temporarily if a district gives control of the campuses in question to an outside third party. The following year, with the first schools set to cross the 2015 law’s five-year threshold, districts began soliciting outside partners. Some, like Hearne and Waco, created nonprofits to oversee struggling campuses, appointing academics and civic leaders to their boards.

Others invited in existing charter school networks. San Antonio Independent School District asked the RELAY Graduate School of Education to take over two schools and, using a grant from the HEB grocery giant, renovated a historic downtown building to house CAST High School, operated with a dozen business, civic, and higher education partners.

One of the outside partnerships helps high school students who are far behind catch up, several provide high-quality early childhood education, and some feature wraparound social service supports.

Houston’s board, by contrast, ran out the clock, declining in April to vote on a lone turnaround proposal from a local charter school network with a mixed track record. State Education Commissioner Mike Morath, considered reluctant to make the state’s largest district a test case for the takeover law, granted a one-year waiver, citing turmoil from Hurricane Harvey.

Weeks later, with at least four schools likely to make the 2019 list of chronic underperformers and no talk of a resolution among school board members, Houston Mayor Sylvester Turner said he would form a nonprofit to run 15 of the city’s academically struggling schools.

Yet on Dec. 6, Houston board members voted 5-4 not to entertain proposals for possible partnerships. Overruling a minority call to at least consider the alternatives, the majority rejected the policy as a step toward school privatization.

“If we don’t take a stand, there’s no pressure on the legislature to fix the underlying problems,” said trustee Elizabeth Santos. “As a board, it is irresponsible to give away our students, especially when we haven’t exhausted all our options, including suing the Texas Education Agency.”

HISD, teacher unions seek to overturn laws

If it materializes, the lawsuit would be the third legal challenge to the two laws. Last spring, the San Antonio teachers union sued to stop a district partnership with a charter network. In August, the Texas affiliates of the American Federation of Teachers and the National Education Association filed suit in state court in Austin, claiming Morath exceeded his authority when he declared that outside partners had to have total control over staffing their schools.

The district and the unions also plan to lobby the Texas Legislature, which opened its biennial session Tuesday. Houston ISD is expected to press for changes to the law to create a higher bar for state intervention. Instead of one chronically underperforming school, district lobbyists have suggested the law should identify a percentage of schools — say 10 percent, or in Houston’s case, some 28 schools — that must be lagging in order to trigger intervention.

Both the lawsuits and the lobbying efforts are likely to be steep slogs. The laws in question cleared both chambers of the Texas legislature with only a handful of “no” votes. The Texas Association of School Boards, for one, has said overturning the laws is not on its agenda for the upcoming session.

Growing awareness of the way some schools have taken advantage of the policies seems to have quelled objections. The legislature two years ago increased funding for charter schools to make up for the fact that unlike traditional district schools, they do not receive facilities funding — a major inequity. Schools placed into partnerships under the 2017 law are eligible for whichever is higher in their community: district- or charter-level funding.

This can mean a per-pupil premium worth $1,300 to $1,800, or as much as $30,000 per classroom in many districts. The money can be used to pay for teacher raises, dual-credit or early college programs, teacher residencies, pre-K programs, and other hard-to-finance items on district wish lists.

In the Rio Grande Valley, Superintendent Daniel King of the Pharr–San Juan–Alamo Independent School District proposed creating several nonprofit “innovation management organizations” to take over all 43 of his campuses. Schools would gain autonomy, and the extra $900 per pupil in state funding would be used in part to raise teacher pay, King said.

Concerned that it could affect teacher contracts throughout the district, the local teachers union opposed the plan, which was ultimately rejected, 1,448 to 661.

Partnerships prove popular

In far west Texas, the Midland Independent School District is applying to use the law to create a variety of partnerships. They are working with the nonprofit Young Women’s Leadership Academy network to open an in-district school using its STEM-focused model, exploring a partnership with a charter school operator yet to be named and talking with experts about opening early college and dual-language schools.

Midland doesn’t have the same kind of red-hot rivalry between traditional district boosters and charter schools, said Chief Transformation Officer Elise Kail. “Our No. 1 competitor is private schools,” she said.

The district is in its second year of soliciting school transformation proposals from faculty and staff, she said, and many of the ideas circulated take advantage of local expertise as well as state flexibility to place subject matter experts in career and technical education classrooms.

“We’re overridden with petroleum engineers out here,” she said, by way of example. “It creates the opportunity for business to get more involved in the schools, which is always great.”

Encouraging collaborations with community groups is one reason Raise Your Hand Texas, a nonprofit that advocates for public education, favors the laws.

“CAST” — San Antonio’s business-supported high-tech high school — “is exactly what we hoped for when we supported [the partnership law],” said David Anderson, Raise Your Hand’s general counsel and policy analyst. “Here’s a chance to work with people you should be working with anyway — and get more money to do it.”

For Eric Lerum, chief operating officer of America Succeeds, the specific partnerships are less interesting than what he calls the state’s “hybrid approach” to pushing districts while offering latitude. Not only are state takeovers of struggling districts unpopular, he noted, but state officials are poorly positioned to actually run schools.

“It’s great that the state is saying we want to see a greater sense of urgency, and that they are saying you have to do something,” he said, adding that a concern is traditional districts’ lackluster record of passing the autonomy they get from state authorities on to their schools.

At the same time, school turnaround efforts have their own paradoxes, he said, most notably tension between urging school leaders to look to strategies that have worked elsewhere and encouraging them to try new things.

Houston digs in — again

On Dec. 6, when Houston’s board majority voted not to solicit proposals for placing the district’s chronically underperforming schools into partnerships, interim superintendent Grenita Lathan warned that running out the clock threatened a repeat of last year.

Last spring, district administrators recommended turning 10 schools over to outside providers. But between public acrimony among board members and a short timeline, she said at the December meeting, none of the reputable nonprofits and high-performing charter management organizations that staff had hoped to see submit proposals were willing to get involved.

Instead, a single local charter authorizer — opposed by the union — stepped forward. As an April 30 deadline to apply for state approval for a partnership drew near, the board gaveled to close a meeting marked by angry protests without voting on the issue.

“I’m saddened at this outcome, as it was not at all what I wanted,” board president Rhonda Skillern-Jones said in a statement at the time. “The one positive result from the chaos is that we did postpone a hasty decision, gained some additional perspective, and broadened our considerations.”

After Morath announced that Houston and other districts affected by Hurricane Harvey would get a one-year reprieve from the law’s consequences, Turner, the city’s Democratic mayor, said he would form a nonprofit with the intent of keeping 15 of the city’s most challenged schools out of the hands of a Republican administration.

Five board members, however, said they were not interested in any partnership, friendly or not. At the time this story was published, discussion of possible partnerships was not on the agenda for the board’s Jan. 17 meeting — the last before the Feb. 3 deadline for proposals set by the state.

Dismayed, Sylvester wished HISD “the very best in its efforts.”

No more carrots, said Dutton. Time for a stick.

“Quite frankly, we have already lost an entire generation because of consistently failing schools in HISD,” he wrote in a commentary published in the Houston Forward Times. “How do I know they will get better under HB-1842 [the closure law]? The truth is I don’t. But what I do know is these campuses in Houston’s northeast community face an even bleaker future if HISD continues its current practice of ignoring these schools.”

Help fund stories like this. Donate now!

;)