Attendance Gap: New Data from Minnesota Reveals Chasm in Chronic Absenteeism

Students can’t make up pandemic losses if they aren’t in class. Yet in many schools, 1 in 4 — or fewer — students show up on a regular basis.

Get stories like this delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

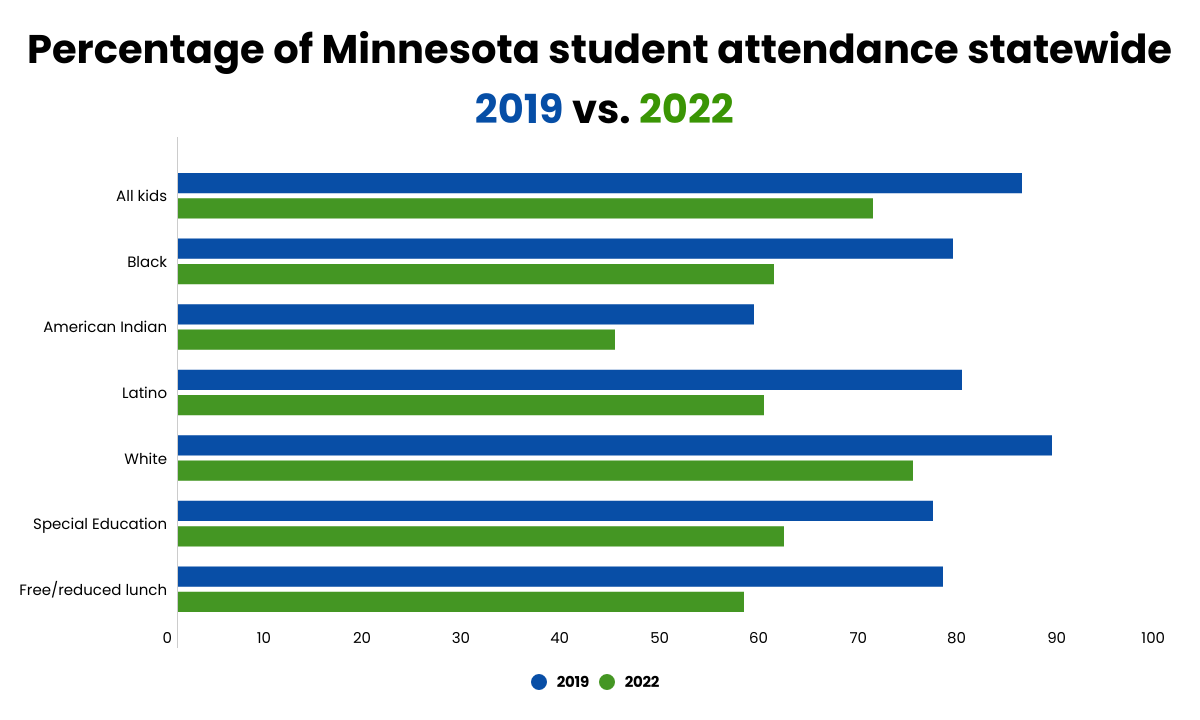

For the first time in four years, Minnesota has released fresh information on one of its key measures of school success: chronic absenteeism. In keeping with an increasingly worrisome national trend, the numbers are dire, with the statewide number of students who attend class consistently dropping from 85% to less than 70%.

That dramatic decline obscures much lower school-going rates among students who have already suffered disproportionately in the COVID-19 crisis. In some of Minnesota’s highest-poverty schools, fewer than 1 in 4 students go to class on a regular basis.

Despite the dismal numbers, there has been virtually no public discussion about the link between students’ chronic absences and continuing declines in reading and math performance post-pandemic. Also unmentioned is the widening gap in attendance and academic recovery between affluent and disadvantaged students.

The new numbers are available on the state’s school data dashboard, but visitors must navigate through several sub-menus to find the relevant information. Data from past years is contained in a very large spreadsheet found on another part of the website.

Defined as missing 10% or more of school days, chronic absenteeism was a crisis before the disruptions of the pandemic and has only worsened. According to Attendance Playbook, a joint report from the think tank FutureEd and nonprofit Attendance Works, more than 1 in 5 U.S. students — at least 10 million — missed more than 10% of the 2020-21 school year. Since schools have reopened, the number of chronic absences has risen, more than doubling in many states.

As alarming as that is, the Minnesota numbers underscore an even harsher reality: As with declines in student wellness and academic achievement, the pain is not distributed equally. The children who were already behind before the pandemic have suffered continuing, compounded impacts.

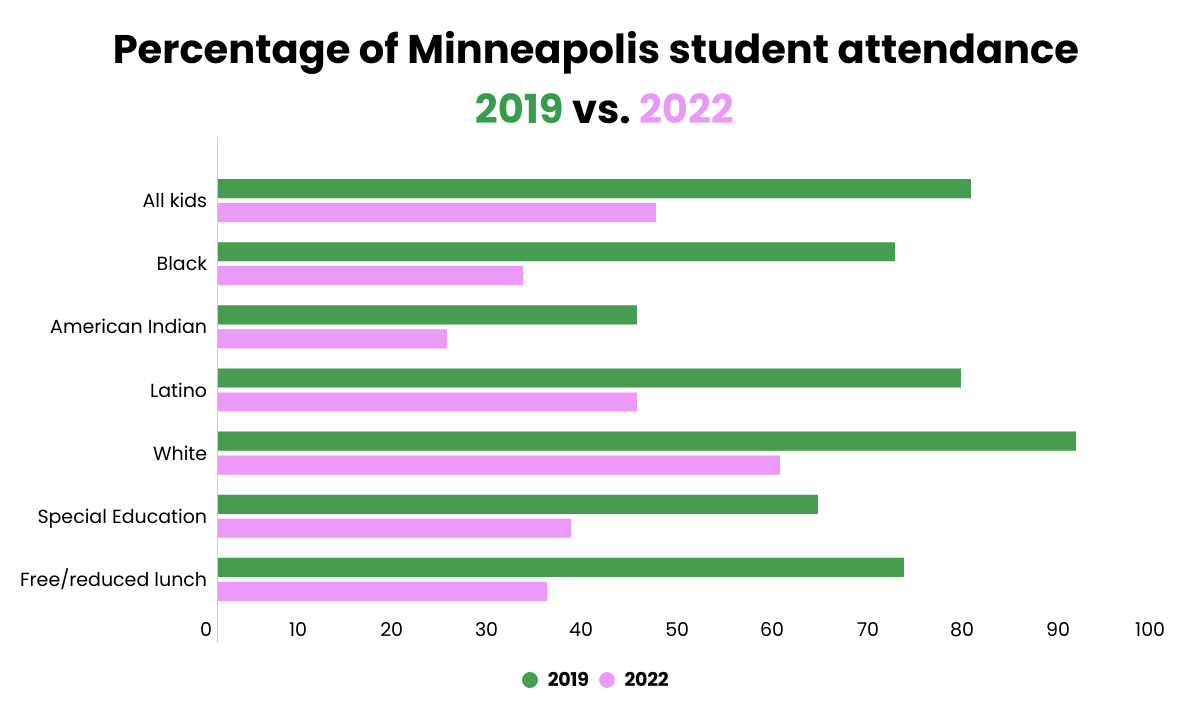

In Minneapolis Public Schools, for instance, the overall attendance rate fell from 79% to 46% from 2019 to 2022. But while the number of white students attending school 90% or more of the time dropped from 90% to 59%, the number for Black students fell from 71% to 32%; for Native Americans, from 44% to 24%; and for Latinos, from 78% to 44%. Attendance among children receiving special education services plummeted from 63% to 37%.

Research showing why it matters is clear. A middle schooler who misses two or fewer days each year has a 93% chance of starting high school on track to graduate, versus 66% for a child who misses two or more weeks. By ninth grade, a week’s absence each semester equals a drop of more than 20% in the likelihood of earning a diploma.

On the most recent NAEP exam, the students who scored the worst had missed the most school before the test. The White House Council of Economic Advisers also released research tying increases in student absenteeism to “a meaningful portion” of post-pandemic learning loss.

Barriers to regular attendance are higher for low-income families, according to Phyllis Jordan, a longtime absenteeism researcher who authored the FutureEd-Attendance Works report. The gap between attendance at wealthy and under-resourced schools has widened.

In 2019, 77% of Minnesota students statewide who qualified for subsidized school meals attended regularly, compared with 57% in 2022. At the district’s wealthiest schools, attendance was high in 2022 — 87% at Armatage Elementary and Burroughs Community, for example. Meanwhile, 25% of children consistently attended high-poverty Nellie Stone Johnson, and just 17.5% at economically disadvantaged Bethune Arts Elementary.

Even more shocking: At Minneapolis’s Harrison Education Center, just 3% of students — one child — attended classes regularly. The center serves students who fit three demographic categories where attendance is historically low: high schoolers living in poverty and on special education plans because of challenging behavioral issues.

Education leaders should be mining attendance data for patterns, says Jordan, whose report outlines a host of strategies for boosting attendance that range from in-school health care to mentorship and student engagement.

“Sometimes it’s a daily pattern, like a lot of kids miss on Fridays, which is not that surprising. There’s some schools that are trying to do some special thing on Fridays now to get kids to come. Maybe it’s everybody in a certain part of town. Maybe they need to start running more school buses,” Jordan says.

The data can also reveal positive outliers that might yield possible solutions. In Minneapolis Public Schools, for example, 57% of students are impoverished and the overall consistent attendance rate is 46%. But in adjacent Robbinsdale Area Public Schools, 61% of students live in poverty but 73% attend regularly.

Similarly, Minneapolis’ Lucy Craft Laney Community Elementary has an impoverished student body and a 49% regular attendance rate — even though it’s located a stone’s throw from similar high-poverty, low-attendance schools.

Minnesota chose to track consistent attendance as a non-academic measure of school performance under the 2015 Every Student Succeeds Act, as did 35 other states and the District of Columbia. As with test scores, public reporting of absentee data was suspended in the 2019-20 and 2020-21 school years because pandemic-driven shifts in and out of remote learning made defining attendance tricky.

Given that lagging attendance was an issue for years even before the pandemic, education leaders should have been mining whatever data they had for information showing which children were engaged in instruction and academic recovery efforts, says Jordan. At the Minneapolis School Board’s June meeting, for example, staff reported that students who used online tutoring appeared to be making good academic progress — but said it was hard to draw definitive conclusions because poor attendance at school, where the digital tutoring took place, meant participation was spotty.

Even though September’s was the first Minneapolis School Board meeting since the state released the 2022 attendance data, the topic did not come up. Instead, board members heard a presentation on the result of 2023’s annual state reading and math assessments, on which disadvantaged students continued to backslide.

Often, low attendance may be linked to obvious causes such as transportation and stable housing. But leaders also need to consider whether a school’s climate is inviting, and if staff have solid relationships with parents — who may have had bad experiences with school themselves, says Jordan.

“There’s often this parent engagement piece you need to do with lower-income families to make sure that parents recognize that these absences make a difference,” she says. “Having a community person or a school liaison or teacher [visit parents at home] to get a sense of what the kid’s home life is like, talk to them about attendance and then have repeat visits, builds that connection.”

Families often have unmet needs, but students also may not feel welcome at school, she adds: “A lot of times if kids don’t feel safe or respected, they don’t come. … The school also needs to create a climate that makes kids want to come to school.”

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)