Pache & Rotherham: Being Prepared for a School Shooting Doesn’t Mean Scaring Kids. It Just Means the Adults Have to Be Ready

Whether by design to spin up parents about guns and electoral politics or because of a lack of expertise in security, districts are responding to concerns about school shootings with measures that, however well-meaning, are doing more to scare kids than genuinely protect them.

It’s important to remember that, while horrific and terrifying for parents, school shootings statistically are quite rare and mass school shootings have declined since the 1990s. Though 57 percent of teens in a Pew Research survey released earlier this month said they were “very” or “somewhat” worried about a shooting at their school, children face far greater risks in their daily lives, so any response should be considered with probability in mind. What’s more, anxious children need not be a byproduct of school security — there are steps schools can take to improve safety that don’t do so much to terrify kids.

When securing a fixed facility such as a school, it’s useful to think in terms of concentric rings. The outermost ring is not a physical barrier but consists of the many resources outside and connected to the school that can be used to prevent or mitigate an emergency. Regular tours by police and other first responders will get them familiar with the grounds and the interior layout. They should also be familiar with the school’s emergency action plan, so they know how the school is responding when they arrive. Developing these plans in coordination with local first responders is an invaluable tool to ensure knowledge is shared and can happen without involving students.

Monitoring students’ social media use can be controversial, but technology exists to scan for patterns and keywords that can alert school leadership to potential threats. This must be done in such a way as to minimize the invasiveness of the program and protect students’ rights. The school should make every effort to ensure transparency in what is being collected and to cultivate an open, non-punitive environment where kids, staff, and parents feel free to report any troubling behavior they encounter. It’s very common for all manner of incidents and potential incidents to be interrupted in advance because kids alerted adults. That stems from a culture of trust and real relationships within the school community.

In the same vein, purely educational steps like better counseling and smaller schools can help. Small schools help adults and students build deeper relationships and make it less likely students will fall through the cracks. The shortage of qualified school counselors has many adverse effects on students, including fewer adults and kids with strong relationships and fewer adults with training about mental health and related issues. Both smaller schools and more counselors are examples of measures districts can take that carry other educational benefits beyond better security and don’t cause stress for students.

The next ring is the physical security of the building itself. An effective entry control plan will ensure that the right people can enter and exit, while unauthorized people are kept out until they can be checked in by staff. These are basic steps: secured doors and a mechanism for buzzing visitors into the building. With proper training and systems, it’s another key step that can be taken without involving students or making them constantly fearful of their safety. Metal detectors have practical and deterrent benefits as well, but schools have to weigh their financial and time costs against the risk. Proper training is key to ensuring both effectiveness and efficiency if schools choose to go this route — and emerging technology can make metal detectors less intrusive.

The last ring consists of the barriers and procedures used to protect the students and staff as well as isolate a shooter as much as possible. Both should be put in place within the tactical framework of Run/Hide/Fight. Existing building and fire codes dictate the types of locks allowed on classroom doors. A solid door that can be locked from the inside is adequate, as there has never been an incident in which a shooter breached a locked classroom door. Doors that swing inward rather than outward are a simple step to make classrooms more secure that students would hardly notice. Automatic fire doors with magnetic locks are often already in place. These can be modified within fire code rules to use as barriers to prevent shooter access to other parts of the school. New technology can identify when and where a firearm is discharged and lock down specific parts of a school to isolate a shooter.

And when new school buildings are being built, as they are in many growing parts of the country, doing so with an eye toward good sight lines and basic security means safety can be incorporated into the architecture in a way that doesn’t make schools feel like fortresses and doesn’t alarm students.

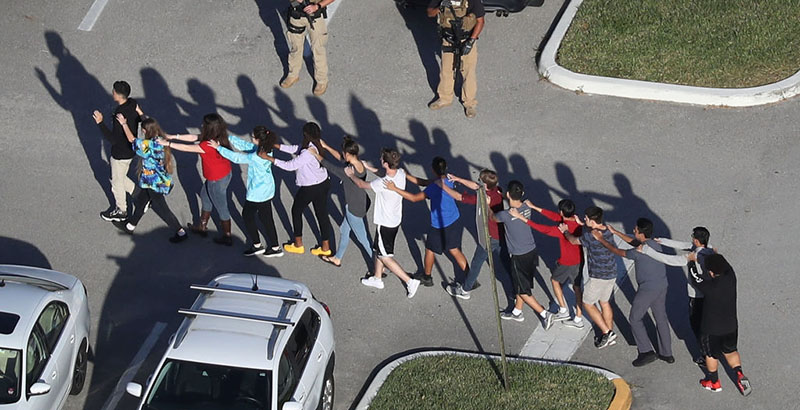

Finally, emergency procedures must be clear, simple, and disseminated to the lowest level. And they must be rehearsed and practiced. Proper training for the adults — not only about active shooters but about the variety of things that can happen in and adjacent to schools — is important. This can also be mostly done without scaring students in ways that are out of proportion to the risks they face; in much of the essential training for school personnel, students don’t need to be involved at all.

None of these strategies is sufficient in isolation. They are merely parts of an overall security approach, one that preferably considers all hazards, and one that all organizations should have in place. Programs can be tailored to fit any budget and can even save money in the long run — for instance, with reduced insurance costs.

The odds are overwhelmingly against a shooting happening at your school, but sadly there is a 100 percent chance that an incident will happen again, somewhere. Being prepared doesn’t have to mean living in fear or creating anxiety for kids. It just means the adults should be ready.

Drew Pache is a former Army Special Forces officer with numerous tours in Bosnia, Iraq, and Afghanistan. He is currently senior manager for security operations at a global risk management company. Andrew J. Rotherham is a co-founder and partner at Bellwether Education and a senior editor at The 74, and serves on The 74’s board of directors.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)