‘One Foot in Puerto Rico, One Foot Here’: High School Seniors Who Fled to the U.S. Mainland After Hurricane Maria Recount Their Tumultuous Path to Graduation

Karla Burgos Santana didn’t want to talk to anyone.

Only hours before, she was in Naranjito, Puerto Rico — the rural town in the mountains where she’d grown up. A senior and aspiring actress, she’d finally nailed a coveted leading role in her school’s musical, Young Frankenstein. Yet on Oct. 10, following the island’s devastation from Hurricane Maria, Burgos Santana was walking the unfamiliar hallways of Cypress Creek High School in Orlando, Florida, feeling depressed and helpless.

“I sat at lunch alone” the first few weeks, the 17-year-old recalled. “I even wrote letters telling myself that I didn’t want to be there. I was mad.”

But eight months later, Burgos Santana has received her high school diploma, one of hundreds of seniors who came to the U.S. mainland to do so. The seniors were among an estimated exodus of about 40,000 students forced to relocate as the island struggled for weeks to regain power.

Dropped into an unfamiliar world, they faced tremendous obstacles: They navigated new school climates, language barriers, and shifting academic requirements, often with loved ones hundreds of miles away. Many came to school districts with sizable Puerto Rican populations, such as those in Orange and Miami-Dade counties in Florida; Holyoke, Massachusetts; and Hartford, Connecticut.

These districts offered a vital sense of community. In Orange County, portable Wi-Fi hotspots kept students connected. A therapy group in Holyoke offered a sense of security. And in Hartford, bilingual teachers came out of retirement to help, and schools bought coats, scarves, and gloves for students who’d never seen snow.

“We don’t close the door on anyone,” said Leslie Torres-Rodriguez, Hartford Public Schools’ superintendent. “You have to respond.”

A New Normal

For Burgos Santana, Orange County’s Cypress Creek High was a 3,200-student behemoth — more than four times the population of her school back home. And instead of staying with the same group of 25 to 30 students for all of her classes, each period was a sea of new faces.

Also new was the school’s advanced technology. Computers largely replaced notebooks. There were trainings for using internet platforms such as Canvas, and Wi-Fi hotspot devices for those who lacked stable connections outside of school.

“People even have walkie talkies to communicate with faculty,” she added, amused.

On top of the initial culture shock, developing course schedules was tricky for those without immediate access to school transcripts and records. Many districts initially enrolled students who were missing documentation, and conducted extensive interviews to gauge their academic history — all while collaborating with Puerto Rico’s Department of Education to transfer records online.

Staff “spent a lot of time trying to get in touch with schools,” said Mary-Beth Russo, Hartford Public Schools’ acting director of English Learner Services. “They’d get in touch with … family members [who] could’ve gone to a school once it opened to take a picture of a transcript.”

Puerto Rico Education Secretary Julia Keleher did not return The 74’s request for comment.

Just as important as retrieving records was re-establishing students’ sense of belonging. In Hartford, there were various activities for upperclassmen and their families — literacy and multicultural nights, dances, fundraisers, and museum trips — to weave them into the fabric of the community, said Torres-Rodriguez, the Hartford superintendent.

As someone who herself had migrated from Puerto Rico to Hartford at age 9, Torres-Rodriguez understood the need for these efforts on a personal level.

“I did not want to leave home; it was what I knew,” she remembered. Her mother, who wanted “safer opportunities” for her and her brother, had taken them to live with distant relatives in a cramped, one-bedroom apartment. “I can’t even imagine adding a natural disaster on top of that.”

Burgos Santana found some semblance of normalcy this year in a theater class, where she helped pen a Christmas-themed play to perform at her school’s choir concert. She played a Puerto Rican grandma.

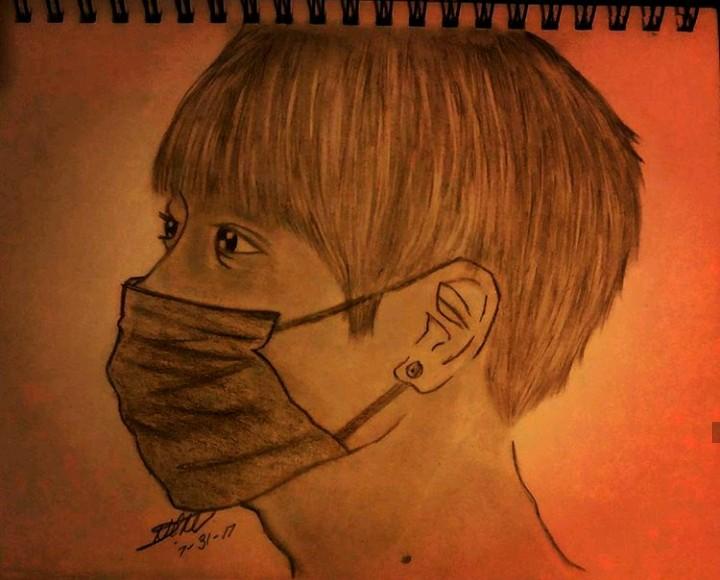

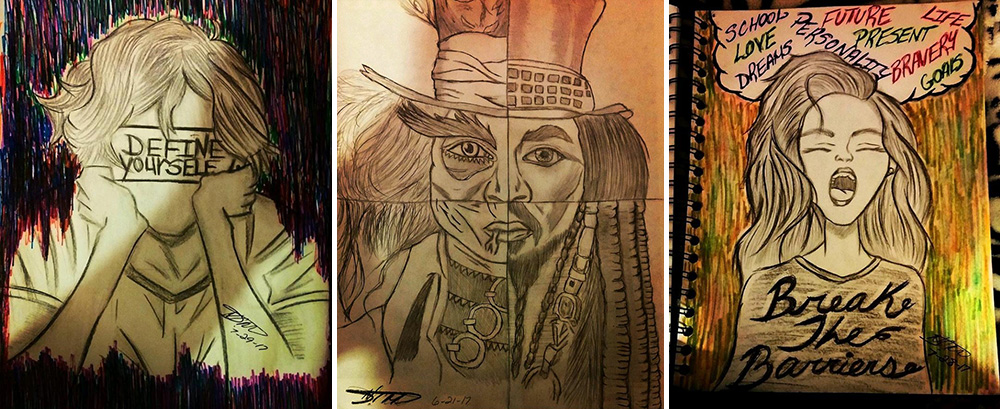

Nicole Class, a senior at Bulkeley High School who came to Hartford from Lares, Puerto Rico, found comfort in two art classes and a student portfolio competition in the city’s Youth Art Renaissance show.

The portfolio she submitted speaks to the challenge of revealing one’s true self to the world — a challenge she confronted personally as a displaced student. In one of her portraits, which combine drawing and acrylic painting, a man hides part of his face before choosing to expose it.

Class competed against about 10 other Hartford juniors and seniors. She won first place.

“Since I was little, I always enjoyed drawing and expressing myself with my drawings,” she said. “When I came here, I expressed it more, because I’m taking the classes.”

Rising Standards

Felipe Almodóvar used to play basketball almost daily for his private school and local club in Río Grande, Puerto Rico, dominating as a point guard and shooting guard. But after transferring to Cypress Creek, he was lucky to shoot hoops even four or five times a month.

The culprit was academics. “I didn’t have time,” he said. “Puerto Rican students didn’t have time. We had to work.”

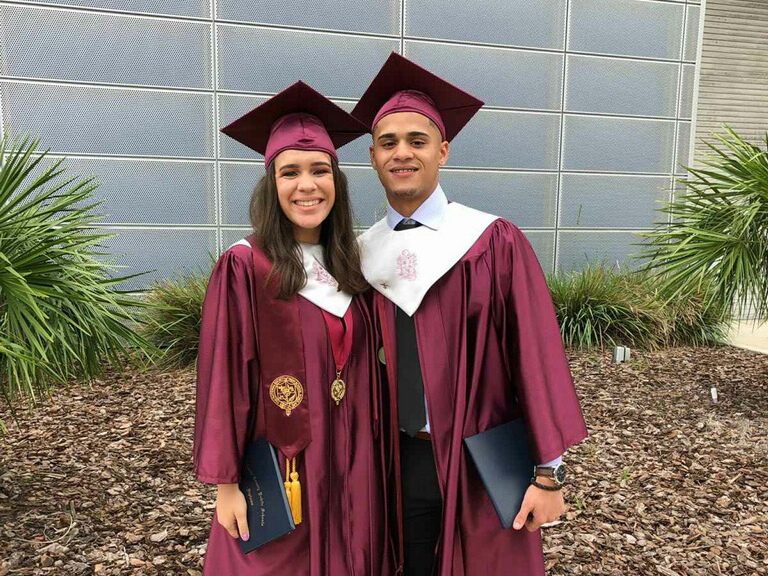

Almodóvar, 18, graduated in late May with a Florida high school diploma — a feat that required passing the state’s graduation requirements.

Graduation requirements vary by state: Students in Florida, for example, have to pass the Florida Standards Assessment or receive a comparable score on the SAT/ACT to graduate. In Massachusetts, passing the Massachusetts Comprehensive Assessment System (MCAS) is a must, while Connecticut doesn’t hold students back for not passing state exams. States with stricter requirements, such as Florida and Massachusetts, however, gave seniors a reprieve: They could pursue a diploma from Puerto Rico if they fell short of state requirements. (An island diploma doesn’t mandate standardized assessments and requires fewer mandatory credits than most states.)

Throughout the year, educators ensured these students had options that matched their abilities and ambitions. Although Almodóvar started out in English as a Second Language classes — which permitted using class notes on tests and taking extra time — his guidance counselor saw he wasn’t challenged and transferred him out after about a month. Suddenly, Almodóvar was in honors English, honors physics, and AP Spanish.

“It was not easy, but I took [those classes] because I knew I could do it,” he said. “[My counselor] believed in me.”

Burgos Santana, also at Cypress Creek, hunkered down on SAT/ACT prep in a class that taught students testing tricks and how to improve reading speed. (Orange County Public Schools provided SAT/ACT test waivers for displaced students, a spokeswoman confirmed.) She also had tutoring every Thursday from November to March with her math teacher to practice for a test that determines college course placement.

Not all students, though, could speak English as well as Almodóvar, Burgos Santana, and Class. Districts tackled language barriers accordingly: In Holyoke, a “Newcomer Academy” conducted courses in Spanish for non-English speakers. In Hartford, 18 bilingual tutors were added to accommodate the influx of Puerto Rican K-12 students — 86 percent of whom were English language learners.

Eleven of those tutors came out of retirement; three were displaced educators from the island. For 17.5 hours a week, they sat alongside students in class, addressing their questions and reviewing material in groups.

Bulkeley High in Hartford even gave Puerto Rican seniors a unique option to research and present their mandatory senior capstone projects in Spanish. About half of the graduating seniors nonetheless insisted on presenting in English.

“I asked their teachers, ‘Are [the students] sure that they want to do this in English?’ ” Russo said. “And they said they’d asked the students, and they were really adamant.”

Providing quality instructional support for these students hasn’t come without financial burden: Hartford shouldered an estimated $3.1 million in costs this year for the more than 450 Puerto Rican students who came to the district. And Holyoke, which has 171 of these students remaining, confirmed that educating one student has a $12,900 annual price tag.

All of the districts contacted by The 74 are awaiting word of federal assistance after applying for funding earmarked for displaced students. Some have relied in the meantime on alternative funding streams, such as state allocations and grants.

‘You Stay Brave as Long as You Can’

Class has lived with her sister in Hartford since early November, but until June, she hadn’t seen either of her parents since leaving Puerto Rico. She reunited with her mother at graduation, but her father couldn’t make it.

As the 18-year-old spoke of her parents to a reporter on speakerphone, the line suddenly went quiet. Gretchen Levitz, Bulkeley High School’s program development director, took over.

“It’s really hard for an 18-year-old to talk about things like this without being emotional,” Levitz said. “You stay brave for as long as you can. She’s done an amazing job.”

For many students, moving to the mainland has exacted a significant emotional toll. Students miss the families, friends, and homes they left behind. For some, the resulting guilt and sadness has become an albatross. Many also grapple with uncertainty about their futures. It wasn’t uncommon for students to leave during the year — districts such as Orange County, Miami-Dade, and Holyoke saw a third or more of their K-12 students from Puerto Rico withdraw. Hartford’s number of seniors alone dropped from 23 to 15.

All of the officials The 74 interviewed emphasized the support systems their schools erected for these students — from regular check-ins to counseling and therapy.

Class is grateful that educators and counselors were “always calling me [asking] if I’m OK, if I need help.”

“When I saw the teachers, saw that they helped us, I knew I made the right decision to come here,” she said.

At Holyoke High School, a licensed social worker led therapy sessions every other week for displaced students. It was “a way to support them and check in with them on a regular basis,” said principal Dana Brown.

The check-ins weren’t only via counseling; Brown chatted with a student in the cafeteria, for example, on a nearly daily basis. “She would fill me in,” he said. “Communication was good.”

Project UP-START, a Miami-Dade program that targets students who qualify as homeless, also financed graduation rites of passage for eligible seniors. This entailed covering senior breakfast and a “grad bash,” as well as providing caps and gowns and access to a “prom boutique,” program manager Debra Albo-Steiger said. (Thousands of Puerto Rican evacuees nationwide struggle with housing instability.)

“They’ve had a lot of emotional turmoil, so they were very excited” for those experiences, Albo-Steiger told The 74. She recalled one senior who’d broken down in tears while picking out a prom dress. She’d been “couch surfing” since leaving the island.

“It was very emotional for her,” Albo-Steiger said. “She was really excited to be going to prom and to graduate.” Albo-Steiger was unable to provide the number of seniors from Puerto Rico in the UP-START program.

But even with a host of resources at their fingertips, some students like Burgos Santana were hesitant to seek help. In those cases, blossoming friendships proved vital. Her new friends — including Almodóvar — quickly became her confidants. Her cheerleaders.

“I actually hated him at first,” she said, laughing. They’d met in the hallway, standing next to each other as they waited in line to take a state exam in November. “But then I met him fully, and now we talk like every day. We understand each other through what happened.”

Graduation and Beyond

Graduation has now come and gone for most school districts, capping off a year no one could have anticipated. For administrators, the overwhelming emotion is one of pride.

For a district “to know and anticipate that [they] will have what is considered a crisis” but then turn that crisis into “an opportunity to meet students where they are at and provide for each and every one of them — that is equity,” Torres-Rodriguez said.

Looking forward, a common goal among the districts has been transitioning these students from high school to college. Class, along with six other graduating Hartford seniors from Puerto Rico, is a part of the district’s summer college readiness program with Central Connecticut State University (CCSU). During the school year, these seniors befriended college-age mentors at CCSU who — like them — fled the island. Now, starting in July, they’ll attend a five-week program on the campus to assimilate and register before starting classes. (Holyoke also established points of contact between its seniors and Holyoke Community College, where a few are slated to attend, Brown said.)

“I’ve gone to the campus two or three times, and they’ve received us with open arms. They’re really attentive,” Class said. She already has a CCSU lanyard.

Class has four weeks of free summer art classes ahead, too, after winning the student portfolio competition.

Meanwhile, Almodóvar is home in Puerto Rico for the summer, but said he’s returning to Florida in August to start school at Embry-Riddle Aeronautical University in Daytona Beach. He plans to study aeronautical science and one day fly commercial airplanes.

As late as January, Burgos Santana still wanted to return to Puerto Rico. The anger she’d felt initially had ebbed, but it lingered. She applied to two universities in Puerto Rico, along with Valencia College in Orlando. Burgos Santana was accepted to one university in Puerto Rico, but it didn’t offer the career path she wanted. Valencia, which also accepted her, was “great” for studying drama and allowed her an option to transfer to the University of Central Florida after two years. So she chose Valencia.

The decision wasn’t easy. She didn’t have an “Oh my god, I got into the university I really wanted!” moment. She now sees herself as having “one foot in Puerto Rico, one foot here.” Home is in Puerto Rico, but her mother is also now in Florida, and the two have grown closer.

Burgos Santana is still figuring it all out.

“I would rather stay,” she said. “Not because I have to. Some part of me wants to stay.”

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)