Brooklyn, New York

New York State education officials — including Commissioner MaryEllen Elia — stopped in Brooklyn Tuesday evening to solicit the latest round of feedback on the state’s policy plan to carry out the Every Student Succeeds Act.

The visit to the Prospect Heights Educational Campus, which houses several specialty high schools, brought out more than a hundred parents, students, and educators, many of them worried about how ESSA’s graduation benchmark might hurt their school, which serves students who have dropped out or fallen behind in credits.

It was Elia’s latest leg in a monthlong tour around the state to gather public input on the plan before the final version is submitted to the U.S. Education Department in three months. Previous stops were in Rochester, Plattsburgh, Syracuse, Long Island, Yonkers, and other New York city boroughs; the traveling hearings wrap up June 15 in Albany, with written comments accepted through June 16.

ESSA, the new federal K-12 education law that replaces No Child Left Behind, shifts much of the power and decision-making in education back to the states from the federal government. New York is among the majority of states that will submit its plan to the department in September, the second of two deadlines.

Based on the

159-page blueprint adopted by the New York state Board of Regents in early May, officials envision a system in which student academic proficiency is still the central measure for evaluating schools, but equity gets greater emphasis — meaning consideration of what resources schools get, including money, quality teachers, and access to advanced coursework.

The state, according to the draft released publicly for the first time last month, will use two main school-quality indicators for evaluation purposes: “improving college, career, and civic readiness,” which includes schools’ offerings of advanced level coursework; and the rate of chronic absenteeism, generally defined as when a student misses 10 percent or more of the 180-day school year.

ESSA also requires states to report four-year graduation rates for low-performing schools, identified as those that fail to graduate one-third or more of students, or those with a graduation rate lower than 67 percent. (It should be noted, though, that after Congress in March dropped key Obama-era accountability regulations for ESSA,

the implications are a lot fuzzier.)

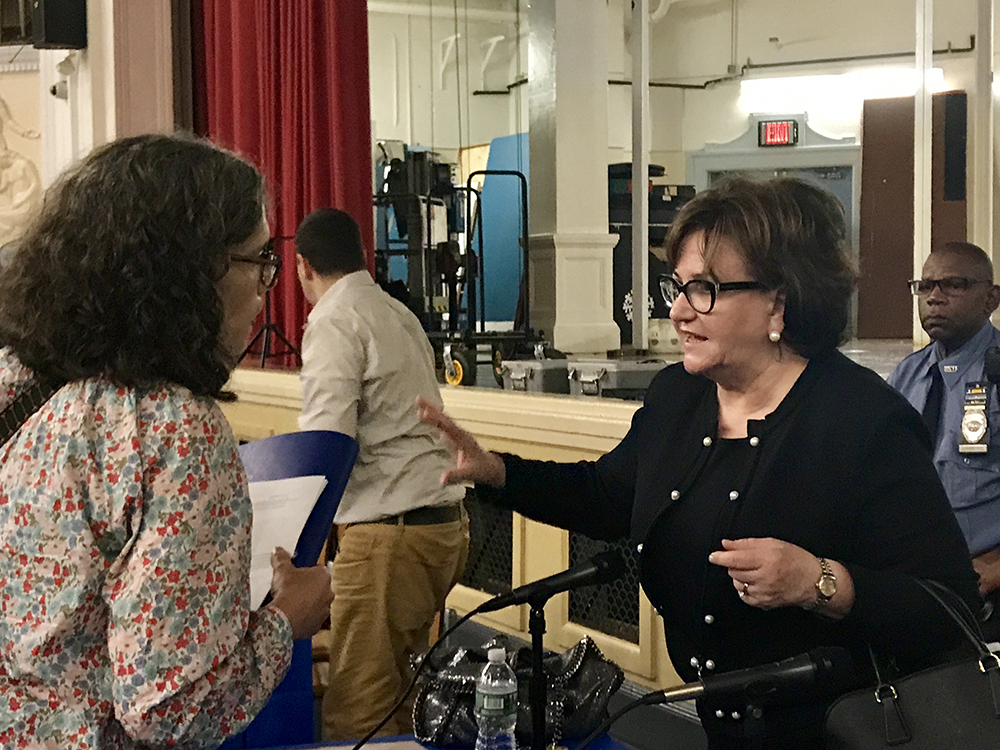

New York State Education Commissioner MaryEllen Elia speaks with a parent Tuesday night after a public hearing on the state's ESSA plan in Brooklyn.

The audience at Tuesday night’s hearing decried the potential impact of that benchmark on New York City’s small but stalwart community of

transfer schools, where students ages 16 to 21 can enroll after they’ve gotten off track in their in traditional high schools. Fifty-nine transfer schools serve about 15,000 students and offer a path toward a Regents diploma or alternative high school completion as well as paid internships. The schools’ environment of intensive support includes counseling, tutoring, and job training.

But a majority of transfer schools post four-year graduation rates well below 67 percent, speakers said Tuesday, describing that as a potential doomsday trigger under ESSA, since failing to meet performance standards would prompt state intervention.

(Citywide, the four-year graduation rate for transfer school students was 22.2 percent, and the six-year graduation rate was 46.7 percent, a Department of Education spokesperson said.)

It could also damage the reputations of transfer schools, speakers said at the hearing, making quality teachers less inclined to work at them and weakening what is often the last shred of hope for teens struggling with the traumas of poverty, physical or sexual abuse, gang violence, or incarceration.

A few students and alumni tearfully described how close relationships with teachers and counselors at transfer schools provided a lifeline as they worked toward graduation while coping with homelessness and mental illness. Others handed state officials poster board signs, such as one that read “Mistakes are proof of trying.”

Ashlie Rivera said she was evicted from her apartment while attending South Brooklyn Community High School but eventually graduated on time with excellent grades.

“Now I’m in college, studying to become a teacher, and if it weren’t for these amazing men and women in my life, I wouldn’t be here right now,” she said, turning to gesture to her former teachers in the audience. Although she was able to graduate in four years, some of her peers require more time, she added, and she urged state officials to consider extenuating circumstances.

Graduates from other city transfer schools told Elia about the life-changing opportunities the schools presented them, like a paid videography internship that led 2012 South Brooklyn Community High School graduate Stephanie Gaweda to a career as a

documentary filmmaker. One of her first projects was a documentary homage of sorts to her alma mater.

Parent Jaimie Hawkins proudly read aloud the 2015 city Department of Education letter she saved confirming that her son with disabilities secured his diploma from Brooklyn Frontier High School.

“What I want you to see is the proof that alternative schools work,” she said, holding up the letter and drawing applause. “I beseech you and I beg you to please do not change anything in terms of how services and programs are offered at alternative high schools.”

United Federation of Teachers special representative Pat Crispino told state officials, “I have high regard for you, but the plan that you have, this room is going to be empty in a couple years because these schools are going to close. It’s not going to work. Teachers are not going to want to go to a transfer school if they’re held to the same standard, because they’re going to be doomed to fail.”

The 2½-hour session was mostly devoted to listening, and Elia and the two members of the Board of Regents with her, Luis Reyes and Kathleen Cashin, didn’t respond to speakers.

Afterward, in a brief interview, Elia disputed the notion that the state’s ESSA plan would automatically target transfer schools as failing, condemned to closure.

“That’s not the case,” Elia said. “It doesn’t mean that a school closes; it means that they are identified as a school that needs to target some change and some improvement.”

She said she met earlier Tuesday with Superintendent Paul Rotondo, the city education official in charge of transfer schools, and City Schools Chancellor Carmen Fariña and promised to work with them to find an approach “that will be reasonable for them.”

“These voices were very important for us to hear,” she added. “And I’m very glad especially that the students came out to talk about those things.”

ESSA is flexible in ways that might address some of their concerns. For example, it allows districts to include students who graduated in the summer after their fourth year of high school in the four-year graduation rate. It also permits states to use extended-year graduation rates for students, and some states are including five- and six-year graduation rates,

Education Week reports.

New York, too, will take this approach, a state Education Department spokeswoman said Wednesday in response to follow-up questions from The 74. Although ESSA does not exempt special schools such as transfer high schools from the 67 percent graduation requirement, New York officials will consider any high school posting a four-, five-, or -year graduation rate at or above 67 percent to have met the requirement, the spokeswoman said, which provides some wiggle room for struggling students.

About a dozen advocates gathered outside ahead of the hearing to criticize aspects of the plan, protesting in particular what they described as an arbitrarily punitive provision that would assign students who opt out of the annual state tests a “1,” the lowest score, when reporting school- and district-level performance to the federal government. Hundreds of thousands of students have sat out the tests in recent years; Long Island districts saw

more than half of their eligible students refuse to take the tests this year, though New York City schools experience few opt-outs.

Asked for comment, the state spokeswoman said the state must adhere to federal requirements on reporting students who opt out of the tests. In its own accountability plan, however, it will consider only results from students who actually took the test. Both metrics will be used to inform decisions about the accountability status of schools, the spokeswoman said.

Among those protesting were stakeholders who provided input on the plan during weekly meetings and monthly sessions in Albany since August as part of the education department’s “ESSA Think Tank.” But the department chose not to incorporate the wider range of school quality indicators some recommended — including teacher attrition rate, average level of staff experience, and whether full-day kindergarten, arts education, and physical education are offered and to what extent. It said quality indicators were too few and high-stakes, raising concerns schools might, for example, push out chronically absent students to meet the standard.

In a press release, advocates said Elia “let down” New York students, parents, educators, and schools and submitted an accountability proposal to the Board of Regents that “squanders the opportunities that ESSA confers.”

In the plan, however, state officials noted that they’ll actively move toward expanding the list of school quality indicators in the future and task a stakeholder group to help make them measurable so they can be used to meet ESSA’s accountability requirements.

School suspension data, school safety incidents, per-pupil school funding, and class size are among the indicators they listed that would be fairly straightforward to measure. More difficult to measure may be access to high-quality teachers and counselors, student integration, parent involvement, and post-graduation outcomes.

(The 74 Exclusive: How Safe Are NYC’s Schools? New Interactive Map Compares What Teachers & Students Are Reporting)

To submit comments on New York’s ESSA plan: Email [email protected] or write to New York State Education Department, ATTN: ESSA Comments, Office of Accountability, Rm 400, 55 Hanson Place, Brooklyn, New York 11217

;)