Oakland’s New Superintendent Is a Homegrown Leader for a District in Financial Turmoil

The rage was palpable. Oakland community members packed the district room waving signs. They shouted over school board members, screaming, “No cuts!” and “Chop from the top!” They stood in line for four hours to make public comments, voices laced with emotion, all asking the same thing: Why were millions of dollars being taken away from their schools?

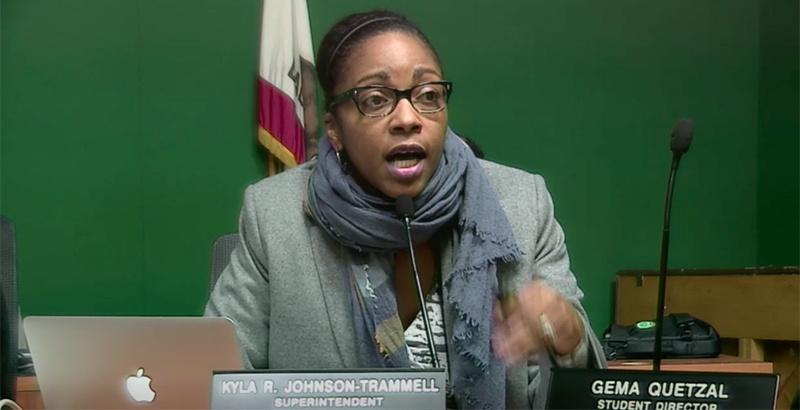

Whatever Superintendent Kyla Johnson-Trammell may have been feeling during that meeting last November, she didn’t show it, even though she had the unenviable task of explaining that “why” to a room pulsing with frustration.

“Before I move any further in the presentation, I would like to say how deeply sorry I am for the current financial position we find ourselves in,” Johnson-Trammell told the crowd that night, in the steady, even tone of a seasoned teacher addressing a room of mutinous students. “I acknowledge and understand the hurt, frustration, and anger that everyone is feeling. For the sake of our children, we must do better as a district and stay committed to fiscal vitality in the long run.”

And while Johnson-Trammell spoke, the people listened, maybe because they felt like she was listening to them.

This is Johnson-Trammell’s first year as a superintendent, and she has inherited a school district in financial chaos. A report released over the summer showed that mismanagement by district leadership, staff turnover, declining enrollment, too many school sites, and inadequate reserves were just some of the many reasons the district was in crisis, at risk of heading toward state takeover.

That turnover included former superintendent Antwan Wilson, who left Oakland after just 2½ years on the job to become Washington, D.C., schools chancellor. (Wilson resigned from his D.C. post in February after he bypassed the lottery so his daughter could attend a popular high school.) In seeking a replacement, community members demanded that an insider take his place, and they like what they got: Even after Johnson-Trammell led the district through $9 million in midyear budget cuts in December, education stakeholders in Oakland are expressing satisfaction with and hope for her leadership.

“I think Kyla inherited a surprising number of deep challenges, and she has moved forward with grace and determination,” Oakland Mayor Libby Schaaf told The 74. “It also gives me confidence that she’s making hard decisions with the long-term interests of the city in her heart. She’s not on some career climb that involves city-hopping. She cares deeply about this community, and she’s willing to do what it takes to put it on the right track.”

Unlike her predecessor, who came from Denver and stayed in Oakland for only a brief time, Johnson-Trammell is a third-generation Oaklander, grew up attending Oakland public schools, and has worked as a teacher and administrator in the district for 19 years, serving under nine superintendents. Making difficult cuts are personal for her; Johnson-Trammell remembers losing her teaching job in 2003, when the district went into state receivership after a similar financial crisis.

Still, she is not afraid to make tough decisions that will affect the community where she has spent her life.

“I want to model being a risk taker so that we can model doing things differently and we can get different outcomes for kids,” Johnson-Trammell said.

More than just a budget crisis

The $9 million cuts include $5.2 million from the central office and $3.8 from schools, which will see layoffs. The district is trying to maintain services that are increasingly important to a community that has seen an influx of students with traumatic backgrounds. For example, the Newcomer Program, which supports unaccompanied minors who immigrated to the U.S., was spared in the cuts, as was the African American Male Achievement program.

But other equally important programs are on the chopping block — and the budget crisis isn’t the only issue that needs attention in Oakland.

The district has long struggled to serve its diverse students, of whom 74 percent qualify for free or reduced-price lunch and 30 percent are English learners. Latino students make up the largest demographic, at 40 percent, followed by 25 percent African-American, 13 percent Asian, 11 percent white, and 11 percent Pacific Islander.

Graduation rates and academic achievement are below state levels. On the 2017 Smarter Balanced exam, 32 percent of Oakland students scored proficient in reading, compared with 49 percent statewide, and 25 percent were proficient in math, compared with 37 percent of California students. Oakland’s 2015–16 graduation rate of 65 percent was well below the statewide rate of 83 percent. Thirteen percent of students are chronically absent.

Gloria Lee, executive director of the nonprofit Educate 78, said she’s heartened to hear that rather than isolating herself with the finance team in the central office, Johnson-Trammell is visiting schools and meeting with students.

“I am worried that the focus on the budget situation is going to overshadow or result in people overlooking the reality that we’re not doing right by so many kids in this city,” Lee said. “I do want the superintendent and staff to be able to spend time in schools supporting teachers and principals to make the changes needed so that kids are ready for careers and college, so they can be proficient citizens in democracy.”

In fact, Johnson-Trammell met with a group of students at the beginning of January to hear their concerns. Edrees Saied, a senior at Oakland Technical High School and a fellow at a local nonprofit education advocacy group called Energy Convertors, was there. During the meeting, Saied said the district’s policy of tracking is unfair, because students who aren’t put on an advanced academic track at a young age aren’t allowed to take specialized programs and classes later on.

“I feel like she was listening. It wasn’t one of those moments where our questions were treated as insignificant; she held our questions to value,” Saied said.

Dirk Tillotson, executive director of the nonprofit Great School Voices, was also part of these sessions and said he was encouraged by how Johnson-Trammell listened and was transparent with the students. “She is thinking about the right things and the politics of Oakland, which is the politics of the possible,” he said.

Taking care of DACA students is also central to the district, especially as their legal status remains in jeopardy. Protecting them is something Schaaf, Oakland’s mayor, said she is willing to go to jail over (she was recently criticized by immigration officials for warning the city about a raid a day before it happened), and Johnson-Trammell released a statement affirming Oakland’s status as a Sanctuary District, where schools will never ask for proof of legal immigration status. “Hundreds of undocumented, newcomer, and refugee students are thriving in our schools with help of the Office of English Language Learners and Multilingual Achievement (ELLMA), and we want to keep it that way,” the district’s website said.

But are the cuts enough?

To some observers, Johnson-Trammell’s story sounds strangely familiar. In 2003, Oakland was led by a homegrown superintendent, Dennis Chaconas, who had taught in the district. He was popular — he improved academics and raised teacher pay — but in the end, he couldn’t lead Oakland out of a budget crisis. The state took over the district, lending it $100 million — a loan it is repaying to this day.

Can Johnson-Trammell avoid a similar fate for the district? Not everyone is sure.

School board president Aimee Eng said the budget is in a better place this year and that the cuts made in December addressed the challenges of the previous fiscal year. “This year, enrollment is up, signs are that we are in a more stable place this year, and the governor’s budget came out and it looks positive for education,” Eng said. “I don’t want to paint it all roses, but it’s not as dire as it was.”

But community members still worry that the district won’t be able to make tough calls, such as consolidating schools to save resources. In February, the district’s financial services director said Oakland will need to cut as much as $7 million from next year’s budget if it wants to remain financially solvent, according to EdSource.

Jonathan Klein, CEO and co-founder of the nonprofit GO Public Schools Oakland, said state receivership is still a real possibility and emphasized the need for a community-driven recovery effort. “A pitfall for any community is believing that the answer is a superhero superintendent. What is needed is leadership across sectors,” he said.

Some blame the budget crisis on charter schools, which have been increasing their enrollment while the district’s student population has remained flat. Charters currently enroll 13,000 students in Oakland, compared with 37,000 in traditional district schools. Oaklanders describe the relationship between charters and district schools as contentious, even though charters have existed there for a quarter-century.

“The reason there are so many charters here is the district is lower-performing,” Tillotson said.

Luis Rodriguez has tried to repair this divide as head of Enroll Oakland, an independent nonprofit that has a single enrollment website for the majority of the city’s charter schools. Although the district isn’t ready for a common enrollment system, Rodriguez said, he hopes to align district and charter enrollment deadlines, which are currently a month apart. He also hopes the district will include charter schools in its portfolio as it analyzes how all schools are serving students, a change that could make the overall school system more sustainable.

“Choice is there, but do we have enough quality?” he asked.

Johnson-Trammell has spoken before on the importance of school quality; she remembers boarding the No. 57 bus every morning and riding for 45 minutes to attend an Oakland school with a good arts program, something that was important to her family. “When we talk about quality schools, we don’t want students to have to make a sacrifice,” she said over the summer.

The listening leader

It’s telling that several people interviewed by The 74 shared the same story about Johnson-Trammell. It was from that heated November board meeting. The usual room wasn’t available, and many of the hundreds of people who showed up to testify couldn’t fit. A satellite room was set up for people to watch the meeting, but this only worsened the already tense emotions. But Johnson-Trammell made a visit to this satellite room during the board meeting, to apologize, to talk with the community, to let them know she was listening.

“That demonstrated the type of leader that she is,” Eng said. “She really sees and hears the community; she is a member of our community.”

For Martin Luther King Day, Johnson-Trammell made a video quoting the civil rights leader: “If you can’t fly, then run; if you can’t run, then walk; if you can’t walk, then crawl. But whatever you do, you have to keep moving forward,” she said.

If the message is any reflection on the state of the Oakland school district, it’s not the most cheerful one, but it certainly made clear Johnson-Trammell’s expectations for her community: persistence in all things.

Disclosure: Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, Bloomberg Philanthropies, Doris & Donald Fisher Fund, and Walton Family Foundation provide financial support to Educate 78 and The 74. The Walton Family Foundation also provides financial support to GO Public Schools.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)