NYC Parents Push to Get ‘School Bus Bill of Rights’ on Nov. Ballot After Years of Transportation Failures

Get stories like this delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

Throughout November and December, fifth-grader Tiheem Ortiz consistently missed his favorite class, gym, because the car service provided by New York City Department of Education in lieu of a school bus always picked him up an hour before dismissal.

“It’s not fair, I have gym Tuesday at the end of the day, and I can’t play gym,” Tiheem said.

The DOE had arranged for the car service after Tiheem’s school bus stopped showing up in early November. As a special education student, he is entitled to “service by a yellow school bus” under his Individualized Education Program — a written plan that states what services and accommodations the school district is legally required to provide.

When the bus first stopped coming, Tiheem missed a week-and-a-half of school because he had no transportation from his Brooklyn home to the District 75 school he attended in Queens. District 75 schools educate some 25,000 NYC public school students with moderate to profound disabilities and are scattered across the city, meaning many special education students have long commutes. Their IEPs are supposed to ensure they have busing.

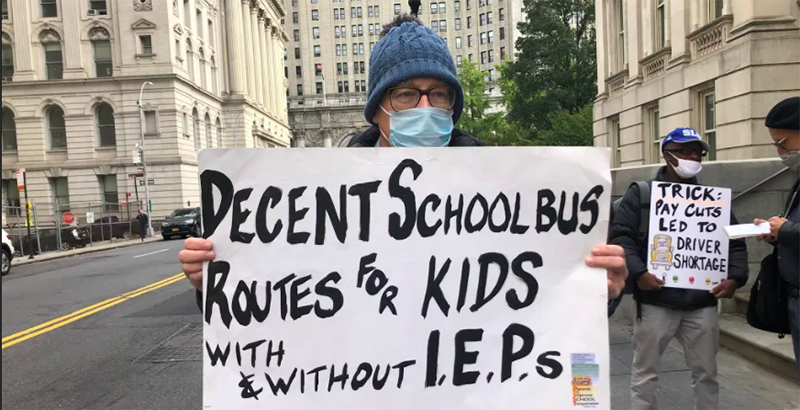

But IEPs are often not enough to deliver on that essential service in the nation’s largest school district, which has a long history of school transportation failures. In an effort to finally force change, Parents to Improve School Transportation announced their campaign to create a school bus bill of rights at a press conference Feb. 4, Transit Equity Day. The event, which had to go remote because of bad weather, was attended by roughly 70 people via Zoom, according to group founder Sara Catalinotto.

“Access to education is a civil and human right, for children of all abilities, all housing [status],” Catalinotto said. “Transit equity, including safe, on-time, fully staffed school bus routes is crucial to their access. … Rosa Parks taught us not to give in just because the system has been so abusive for so long.”

The parent organization is in the initial stages of getting a referendum onto the November ballot in New York City to approve the school bus bill of rights, a process that will require collecting thousands of voter signatures on a petition.

Brooklyn state Assemblywoman Jo Anne Simon and Nick Smith, the city’s first deputy public advocate, both spoke at the press conference and said they would support the referendum campaign. Parents to Improve School Transportation plans to march across the Brooklyn Bridge March 19 to raise further awareness of their effort.

Catalinotto said her goals include increasing measures to prevent route problems, like limiting the number of schools and stops on each route. She also hopes to see steps taken to retain a dedicated workforce. She wants increased workforce training and Covid protections. She is pushing for accessible communication with the DOE’s Office of Pupil Transportation in all languages. Additionally, Catalinotto hopes to create a panel to oversee policy decisions regarding school transportation.

In an email statement shortly after the press conference, DOE Press Secretary Jenna Lyle did not respond to questions about the bill of rights’ demands, but said insufficient busing is not acceptable.

“Every day we provide approximately 150,000 students with quality transportation to and from school, and we are constantly working to improve service,” Lyle wrote. “We work closely with families, bus companies and schools to ensure a safe and efficient experience for all students and staff – anything less is unacceptable.”

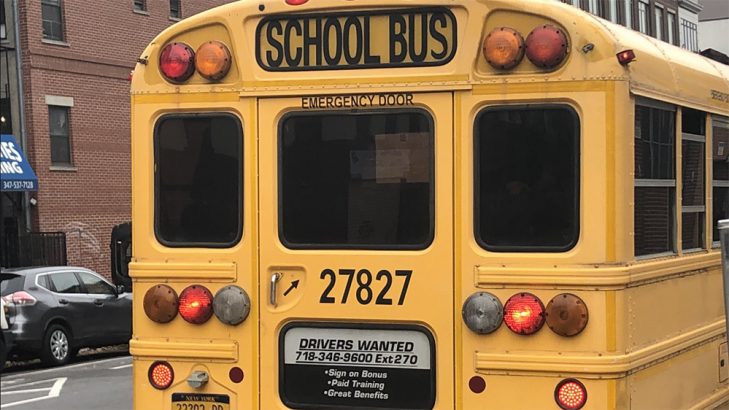

Since the beginning of the school year, parents across New York City have been drawing attention to late, absent or understaffed buses, chronic barriers to their children’s education which grew worse under the pandemic and the ongoing national school bus driver shortage. While some parents who spoke to The 74 said the issues they faced in the fall were resolved by December, they said they are still coping with the academic, economic and mental health repercussions.

“I had to personally put my life on hold,” said Lynette Epps, who had to accompany her son Tiheem in the car service to and from school until he was assigned to a new school in January. “I had to turn down two jobs because of this.”

Others are still missing school due to problematic bus routes. The situation overwhelmingly impacts special education students, who have already suffered significant learning loss during COVID.

Rima Izquierdo — a parent leader and the Bronx representative for the District 75 Leadership Team — said she advocates on behalf of families at her child’s campus. She said one currently has a bus that regularly picks up their child at 9 a.m., 40 minutes after school starts. Izquierdo said her 15-year-old son, whose IEP requires a paraprofessional accompany him on the bus, has also missed a lot of class time.

“I’m sure everyone hears my child in the background,” Izquierdo said during the virtual press conference. “Because of the para shortage, my bus para cannot take a day off or have an emergency without my son not losing the day of school because there is nobody to replace her.”

Izquierdo said the Office of Pupil Transportation said her child would be assigned a new bus route Feb. 14.

In a press release issued after the Feb. 4 event, the DOE said they resolve route issues quickly.

“A vast majority of bus routes run smoothly throughout the city each day. Any one-off issues are escalated and efficiently addressed,” the department said in a statement.

Many NYC school families would disagree. Zariah Jimenez — a 19-year-old high school student at a Queens District 75 school — missed 25 days of school earlier this year because of late buses that violated her IEP’s limited travel time, according to her mother, Cheryl Ocampo. The issue took months to resolve.

Ocampo says Jimenez has trouble waiting for long periods of time and that waiting for the bus triggered her anxiety to the degree it became “a safety concern.” Ocampo had to leave work early to pick up her daughter herself. On days that she couldn’t afford to miss that time away from her job, Ocampo had to keep Jimenez at home.

“This school year’s school bus complications have profoundly impacted my daughter’s overall mental and physical health as well as her education and my employment,” Ocampo said, explaining that Jimenez developed anxiety about the bus, which led to sleeping issues. Ocampo said her daughter’s bus route was resolved in mid-December, but “my daughter is still trying to get back to some kind of normalcy.”

From the start of the school year until Dec. 3, Kelly Muñoz didn’t have a bus that met the limited-travel requirement in her sixth-grader’s IEP. Every morning, Muñoz had to do a two-hour round trip to get her child to and from their District 75 school in the South Bronx to their home in the Northwest Bronx. She said she counted driving 759 extra miles during that time.

“Mentally, I was drained and tired. There were days I was so stressed out from navigating traffic, missing meetings, playing catch up and parenting that I would want to just cry. I was having tons of headaches and even had an eye twitch in my left eye,” Muñoz said. “Taking on the responsibility of the DOE’s [Office of Pupil Transportation] was something no parent should have to do.”

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)