NOLA Social Worker Finds Herself Supporting Students All Day, Every Day During COVID-19

This is one of eight profiles in Displaced: The Faces of American Education, a package from The 74 following the stories of the diverse characters who are a part of the American education system, and how the COVID-19 crisis has upended their lives in a few short weeks. Meet the others, from around the country, here.

For Shawnell Ware, a social worker at McDonogh 35 High School in New Orleans, the work day used to be from 8 a.m. to 4 p.m. Now, with school shut down and her city hit hard by the coronavirus, she’s available to her students, their families and her colleagues anytime, day or night.

On a typical school day before the pandemic, she checked in with students as they arrived at school, monitored attendance, observed classrooms, met with students individually, visited families at home and helped coordinate mental health care and other services for students.

Now Ware, 51, does all that virtually, in addition to checking in with parents regarding their own mental health, working with teachers to modify assignments for students overwhelmed by online schooling, and tuning in to Zoom classes with students and meetings with her colleagues throughout the day.

“I feel like I’m working 24 hours around the clock. Literally, I receive phone calls at 5 o’clock, 6 o’clock, 10 o’clock [at night]. I even had a student [who was experiencing] anxiety one morning call at 5 a.m.,” she said.

She answers every call. “That’s what we have to do to make sure that our students are cared for emotionally, socially and academically — to provide that support,” said Ware, who was just named “Support of the Year” at McDonogh 35 by her principal, Lee Green.

The first challenge when the school moved online was getting McDonogh’s roughly 400 students connected with internet service and devices. Next, Ware had to get used to seeing her students through a screen and communicating via text message, which many of her high schoolers prefer to phone or video calls.

“I miss being face to face because I like to do physical assessments where I can lay eyes on my students … I’m now reading body language via Zoom calls. That’s been a challenge for me,” she said. Still, she’s watching students carefully to make sure they’re OK and looking for “any signs and symptoms of depression, if they look in distress, if they’re looking distraught.”

Ware’s school is part of the Inspire NOLA charter network, and her students are 99 percent black and 85 percent economically disadvantaged.

Ware said she also noticed that many parents were struggling, especially when the shutdown first started, so she talked to them about their own mental health and coached them through setting up routines to help their families adjust to online learning and manage the stress of the pandemic.

The coronavirus has infected more than 13,500 people and killed at least 800 in the New Orleans metro region, and it hasn’t spared the McDonogh 35 community. When the pandemic began, Ware was overwhelmed by the losses, which included some of her close friends and 74-year-old Coach Wayne Reese, a legendary football coach and beloved physical education teacher at McDonogh 35.

The school had a socially distanced procession in McDonogh 35’s hallways for Reese and has set up a memorial in his parking spot. The staff is also planning to remember him again when regular school resumes, possibly naming an athletic facility after him.

“That was a trying time for us. [Reese] was a very big giant — we called him a gentle giant in our lives,” she said. “That was a challenge, and that was a challenge for me as well, with trying to care mentally for everyone else and still having to deal with my own feelings.”

Ware also reached out individually to all of the students who were in Reese’s classes and their families. For many, the coach’s death triggered memories of others who have died or increased anxiety about relatives who are sick or hospitalized with COVID-19.

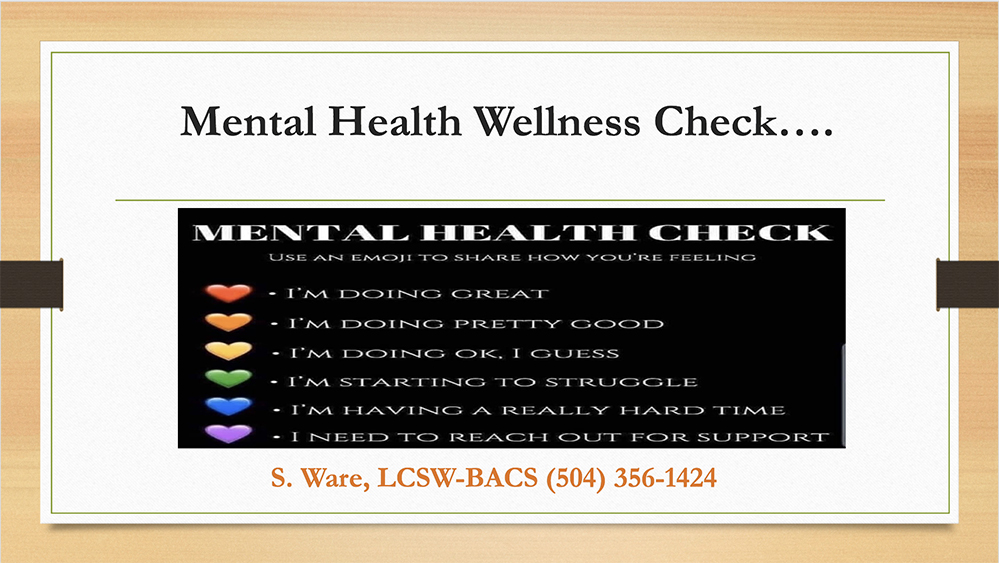

Persisting through tough times is “just part of the ball game” of being a social worker, Ware said. One of the systems she set up to help her community is an emoji code, whereby anyone can text her a heart and the color indicates what they need that day.

“I find my kids communicate better via text, which is crazy and kind of different for me to talk about therapeutic things in a text message, but they seem to be expressing their feelings more via text than actually face to face with the Zoom,” Ware said.

Even with all that she does for her community, Ware takes time to care for herself, too.

“Through this pandemic, I found myself eating and ordering a lot of Garrett’s popcorn, so I had to do some self-care things as far as just increasing exercising for myself,” she said. (Her favorite popcorn flavor is cashew caramel crisp, and she’s sent some to her colleagues in care packages as well.)

Ware, who lives with her husband, also reads, journals, meditates, takes breaks from the news and social media and avoids looking at screens in the hour before bedtime — and recommends that her colleagues do the same.

The school year ended for Ware’s students May 15, but that doesn’t mean the social worker is on vacation.

“My cellphone number doesn’t change. In our Zoom calls I let my students know if they need me, don’t hesitate to reach out, call, text, email, so they still will have access to me,” she said. “The number won’t change and I’ll respond, whether they are in school or out of school.”

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)