The Turnaround Artists at the Center of InspireNOLA’s School Reboot? Parents

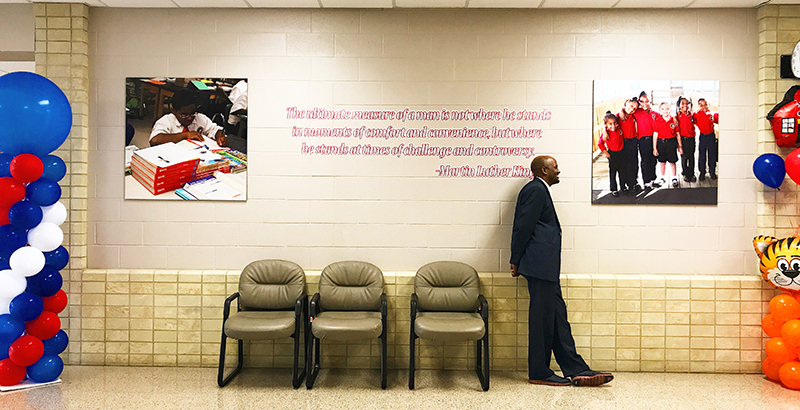

As Vera Sims walks the halls of Inspire42, where her grandson Robbie is in the fourth grade, she stops periodically to take in inspirational quotes posted on the walls. The school is newly renovated, and shadow mullions outline rectangles of sun on fresh paint.

Located in New Orleans’s Tremé-Lafitte neighborhood, these are Sims’s halls. Fed up with bad management and a teacher corps that rotated faster than she could learn their names, Sims is one of the guardians who fought hard to get the former McDonogh 42 Charter School, rated an F on state report cards, turned over to a nonprofit network that runs A schools.

Sims has cared for Robbie since his father died when he was 4. He’s quick and has ADHD, a combination that can make him a handful in the classroom. Instead of entering a quiet retirement, she’s spent a lot of time at school, advocating for the boy and serving as an extra set of hands to keep him on task.

Last year, the school’s former leaders barred Sims from the premises, a move that tapped out her seemingly inexhaustible well of patience. Soon after she was shown the door, Sims learned that McDonogh 42 had chalked up another F on state report cards and was being taken away from its management — again.

In fact, 42 has the dubious distinction of enduring more management changes than possibly any other school in post-Katrina New Orleans. Three times its families have been promised that a new plan would ensure that their kids, born into a city that historically has had some of the lowest educational outcomes in the nation, would learn the skills they need for bright futures.

42 is the second underperforming school the fledgling InspireNOLA network has agreed to take on in as many years. Last year, Inspire took on a different F school, Andrew H. Wilson, which ended the last school year with a C. Wilson’s 2015–16 test scores revealed more growth than any other school in the city, with a 29-point jump on a 150-point scale.

Taking on an F school is a risky proposition. Leaders of the networks, or charter management organizations, that run almost all New Orleans schools live or die by those grades. Common wisdom holds that A operators wouldn’t take on the lead weight of an F school.

Last spring, when The Times-Picayune reported that one of the groups that applied to take over 42 had submitted a plagiarized charter application, it seemed entirely likely history was about to repeat itself.

Parents were invited to participate in the decision to give 42 to InspireNOLA, which boasts two of the city’s most successful A-graded schools, Edna Karr High School and Alice Harte Charter School. Sims leapt at the opportunity.

She had no idea that soliciting parent input into this kind of decision is a departure from business as usual in New Orleans, where outside education administrators are engaged in the process of handing control over schools back to city residents. Parents at InspireNOLA’s first turnaround, Wilson, had to fight to have a say in their school’s fate.

Until recently, a state turnaround agency, the Recovery School District (RSD), oversaw almost all of the city’s schools and made decisions about which charter operators would be allowed to open new schools or turn around flagging ones. The agency got high marks from policy watchers for making tough decisions, but it typically made them from its Baton Rouge offices, out of the public view.

The four InspireNOLA schools are among the first to be returned to the oversight of an elected Orleans Parish School Board.

“We often did things to the community with school siting assignments, not with the community,” Patrick Dobard, then-superintendent of the Recovery School District, told The Louisiana Weekly two years ago, after the Wilson parents demanded — and got — a say.

In a closely watched experiment in radical school reform, after Hurricane Katrina almost every public school in the city got a reboot. Improvement in New Orleans’s schools, long some of the worst in the nation, was swift and dramatic.

But the controversial effort was anything but grassroots, and as the 10th anniversary of the storm approached two and a half years ago, tensions over who got to make decisions about New Orleans’s schools came to a head. The community demanded a voice in the process. A meaningful one.

Nowhere was this more visible than at Andrew H. Wilson Charter School, a K-8 in Broadmoor, a wedge-shaped neighborhood north of New Orleans’s leafy and prosperous districts. Sometimes referred to as “the bottom of the bowl,” the neighborhood is so low-lying, city planners thought about turning it into a park after the storm. Residents wouldn’t hear of it.

Nearly 10 years after Katrina, with persistent financial and academic problems and a grade of F on state academic report cards, the state agency ultimately responsible for the school faced a decision: Close it or find a new organization to manage it.

Realizing they weren’t being included in meetings about the school’s future, a group of about a dozen Wilson parents met in the school’s library and decided to insert themselves into the process. Starting in late January 2015, the parents scheduled tours of schools run by all six charter management organizations — the nonprofit organizations that operate school networks — that could be in the running to take over Wilson.

And they made it clear they weren’t going away, sending emails to officials and news media and securing 250 parent signatures on a petition to be given a seat at the decision-making table. Wilson’s mascot is a wolf; the parents styled themselves the Protectors of the Pack.

“We split up into teams and visited schools,” says Dana Wade, the mother of three Wilson students. “We had two weeks to do it. We were taking off of work to do this. We were totally committed to the process.”

Within days, the RSD gave the group three seats on the committee vetting proposals from would-be Wilson operators. InspireNOLA was the panel’s unanimous choice.

For parent Lamont Douglas, the network’s local roots were key. InspireNOLA was the only homegrown operator under consideration, he says.

“It was almost like they were saying no one in New Orleans can make it work,” says Douglas, whose daughter started fourth grade at Wilson. “There are still a lot of teachers who were in the schools before the storm who are still here. You have people from New Orleans who know how to do this.”

InspireNOLA co-founder and CEO Jamar McKneely was one of them. After college he started work in nonprofit finance, but education tugged at him. “I can remember sitting in my cubicle thinking, ‘I want to do something for kids,’ ” he says. “So I quit my job and moved here.”

McKneely started teaching in New Orleans schools 16 years ago and was one of the 7,500 teachers laid off when schools closed after Hurricane Katrina. When they opened again, he took over as principal of Edna Karr High School. During his watch, the school rose from a D to an A, a feat he repeated at Alice Harte.

Two years ago when InspireNOLA decided to take on more schools, engaged families was one of the things McKneely looked for. “We didn’t care where we expanded, we just wanted to work in a community with involved parents,” he says. “That’s when we met these parents.”

The network had a choice of two programs in need of new management. Turning around Wilson — a school already serving some 600 students, some of them years behind— was the harder job.

“A lot of people are fearful of turnaround work, but who are we to say these students don’t deserve a quality education,” says McKneely. “I think it’s important as a charter management organization that we don’t consider our work done until every child has a quality school.”

The first thing McKneely did at Wilson was painful. After numerous conversations with staff about their vision for the school, InspireNOLA replaced 70 teachers — but in many instances with local veterans and not AmeriCorps volunteers or Teach for America corps members or any of the other youthful idealists who flocked to the city after the hurricane to help rebuild the schools.

McKneely’s bottom line was a belief set. Wilson’s new teacher corps had to believe better was possible. “You’re walking into a culture that is not as structured,” he says. “You’re walking in where the expectations have been very low for years.”

Parents, too, had demanded the school push their kids. “They really went to bat for us,” says McKneely. “It takes away some of the outside pressure, so we can really take some risks, do some creative things.”

InspireNOLA instilled some practices common to high-performing schools. It instituted weekly professional development for teachers, formalized the collection of data pinpointing individual students’ challenges, and ensured consistency from one classroom to another in terms of routines.

Three administrators — each with a desk located, visibly and accessibly, in a hallway — are each responsible for a group of grade levels.

Douglas’s wife now teaches sixth-grade math at Wilson, and some of his own childhood teachers are there, too. The relationships between Wilson staff and neighborhood parents has been key, he says: “Sometimes with kids, you know if you act up, ‘I’m gonna see your mom at the grocery store.’ ”

Dana Wade’s three children returned to Wilson in August for the 2017–18 school year, enrolling in kindergarten, fifth, and sixth grades. Staff knew her youngest daughter before the girl started in its preschool classroom, says Wade.

“We tried to instill a model where kids can learn from their mistakes and really build on their strengths,” says McKneely.

The parents have stayed involved, they say, organizing to support not just traditional PTO projects like band and sports, but working to get “wraparound” social services into the building to address students’ unmet needs.

“Now we have people coming to see what we’re doing,” says Wade. “We’ve gone from being the black sheep to being someplace people want to come study.”

Can InspireNOLA pull off another successful turnaround at 42? McKneely doesn’t see a choice, given the violence, poverty, and other long-term challenges facing NOLA’s low-income kids of color.

“Even before the storm we had to do something different,” he says. “We had people who were working hard, but we needed something different.

“If we’re making academic gains, I’m ready for that to turn into a lower crime rate. We’re ready for that to translate into higher employment rates.”

For her part, grandmother Sims is convinced that this time leadership won’t let 42’s students down. She understands why families are slow to share her conviction, so she’s throwing the energy she used to put into advocating for Robbie into personal outreach to parents, asking them to consider getting involved one more time.

And Robbie? Sims is proud to busting as she says he’s done his own turnaround, earning InspireNOLA’s equivalent of a letter jacket, a gold sweater that signifies having reached the “mastery” level on his exams.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)