New Study of Common Core Reading Standards Finds Teachers Aren’t Giving Students Appropriately Challenging Texts

Five years after implementation of the Common Core State Standards in reading began in earnest, some instructional practices in reading have shifted for the better, while others — most notably teachers assigning texts based on reading level rather than grade level — have actually changed for the worse, a new report finds.

The Common Core State Standards encouraged a number of big changes in American reading instruction, including a shift to more complex texts, particularly nonfiction, and content-rich curriculum. The standards are more rigorous, but can present challenges for teachers, particularly those whose students are behind academically.

A little more than a quarter — 26 percent — of teachers surveyed for a new report by the conservative Thomas B. Fordham Institute said they assign texts based on grade level rather than reading level. That’s down from 38 percent in a 2012 Fordham survey, meaning that fewer struggling readers are being challenged to catch up to where they should be.

Overall, elementary-level teachers are still the most likely to assign based on the less rigorous reading level, but the proportion of middle and high school teachers who do has risen sharply from the older study, from 38 to 58 percent among middle school teachers, and from 24 to 42 percent for high school.

One potential explanation for the marked uptick is that “nearly half of teachers say ‘not enough’ attention has been paid to ‘diagnosing and addressing the challenges posed by a text,’ ” the report authors wrote.

Struggling readers can access grade-level texts with appropriate help from teachers, like early introductions of potentially tricky vocabulary words or “bread-crumbing” questions that help lead students through text, study author David Griffith, Fordham’s senior policy associate, told The 74.

But that’s a difficult skill for teachers to pick up, he said.

“We need to help teachers a little bit here, because we’re asking a lot of them when we say teach grade-level texts, even when [students] are behind,” he said. “They’re not doing it, and it seems likely that’s just part a basic capacity issue.”

The Common Core State Standards is a group of benchmarks for reading and math, developed by state leaders through the National Governors Association and Council of Chief State School Officers. Forty-one states, the District of Columbia, and the Defense Department’s school system have adopted and are currently using both the reading and math standards; a few states adopted and later revoked them.

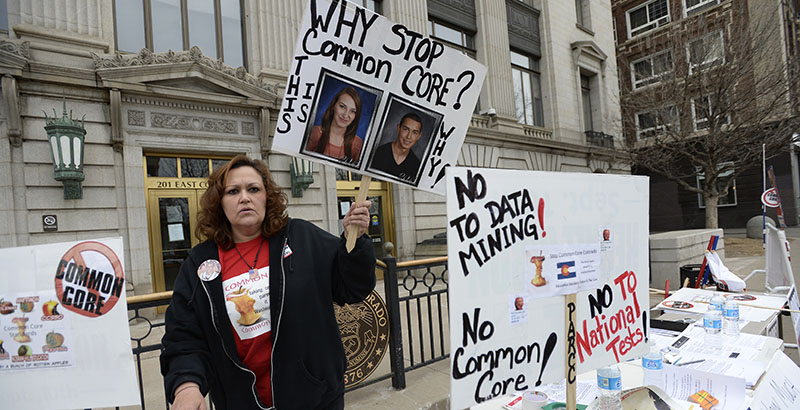

They garnered intense criticism among conservatives as an inappropriate attempt to nationalize K-12 education — President Donald Trump during his 2016 campaign called for abolishing them — and many parents and teachers balked, saying some of the tests aligned to the standards were too difficult.

Teachers surveyed by Fordham also said they’re assigning less fiction and more informational texts. That’s important, given the Common Core’s emphasis on nonfiction, but they also said they’re assigning fewer “classic works of literature,” which the report authors called a “concerning development.”

“Literature should remain the cornerstone of English courses in middle and high school,” the report states.

“Great works of literature” should include literary fiction and nonfiction, as prescribed by the Common Core, the authors said.

“In other words, the reading list should include not only ‘The Great Gatsby’ and ‘Lord of the Flies,’ but also works such as ‘Letters from a Birmingham Jail,’ The Emancipation Proclamation [and others],” they wrote.

Educators should remember that the emphasis on nonfiction is spread across subjects, so history, science, and other teachers as well as English teachers should help students learn to analyze informational texts, the report said.

General content knowledge has also been overlooked, the report found.

More than half of teachers surveyed — 56 percent — said general content knowledge “such as the laws of gravity or who Shakespeare was” have not gotten enough attention in state standards or implementation.

“[General content knowledge is] critical to vocabulary acquisition. It’s critical to reading comprehension. It almost equates to those things. If you don’t know anything about outer space, you’re not going to be able to make sense about a scientific article about it,” Griffith said.

The report offers several recommendations for teachers, including the use of “text sets,” or units focused on one broad subject to help build general knowledge and vocabulary.

School leaders and advocates could work to craft better curricula, particularly ones that offer students the general knowledge they need, Griffith said.

Teachers also aren’t doing enough to push for evidence-based writing, still relying on creative and personal expression, the report said.

On the positive side, teachers are doing a good job teaching vocabulary in the context of reading text, Griffith said.

“The days of sort of disconnected flashcards seem to be over,” Griffith said.

They’re also using appropriate tools to gauge the complexity of texts they’re giving to students, and they’re teaching the “close reading” analytical skills that students need, according to the report.

Researchers surveyed 1,237 English language arts teachers online in fall 2017, and they also conducted a focus group with teachers from Maryland ahead of the survey.

Disclosure: The Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation provided financial support for the Thomas B. Fordham Institute report and The 74.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)