New Report: Despite Red Ink & Academic Losses, School Boards Rarely Talk Budgets

With painful choices looming, a third of boards spent less than 15 minutes considering district finances. More than half of members had no questions

Get stories like this delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

Right now, most of America’s roughly 13,000 school boards are confronting some painful math as they consider next year’s proposed budgets. COVID recovery dollars have run out, and the future of federal education spending is uncertain. Sharp enrollment declines have led to lower state per-pupil funding, and a recession seems likely.

As the people responsible for deciding how to spend some $700 billion in education dollars, school board members, one might assume, are spending a lot of time discussing tough choices.

But according to a new paper from researchers at Georgetown University’s Edunomics Lab, many boards devote as little as 15 minutes to considering possible trade-offs and the impact of spending decisions on student outcomes as they vote on new budgets. Indeed, as millions of dollars are allocated, half don’t ask any substantive questions at all, researchers found.

But the data indicate that educating even a single board member on how spending can impact student learning stimulates more discussion. States could play an important role in making this happen, says the report’s lead author, Edunomics Director Marguerite Roza.

The results suggest that states, which provide the lion’s share of school funding, should consider requiring board members to undergo better training on budgeting, says Roza. Though states bear primary responsibility for holding districts accountable, they rarely demand that boards spend money on the things that most benefit students.

“Most board members have only rudimentary finance training that’s about compliance issues with state laws or audits,” says Roza. “As a condition of giving them the money, [states could require] board members to regularly get some training on the basic role of budget oversight. What is a strategic way to evaluate a budget? How often should they be asking questions about the outcomes, or equity or other kinds of things?”

Published by Brookings, the paper is the latest of three drawn from a first-of-its-kind analysis of hundreds of hours of video of school board budget deliberations, which take place every winter and spring. Using a federal grant, Edunomics researchers streamed meetings that took place in 174 districts of varying sizes, poverty levels and geographic settings in 27 states, tracking the amount of time each board spent discussing revenues and proposed spending, as well as what specific issues members talked about.

The meetings analyzed in the latest report took place in 2023, when districts had wide discretion over an unprecedented $189 billion in pandemic aid intended in large part to boost students’ academic and social-emotional recovery. In theory — with students falling further behind academically, the money set to run out in September 2024 and a fiscal cliff looming — board members should have asked which investments were proving effective and whether budgets should be adjusted accordingly, says Roza.

At the time, the researchers noted, states and the U.S. Education Department were offering districts numerous resources on how to best use the one-time infusion of federal funds.

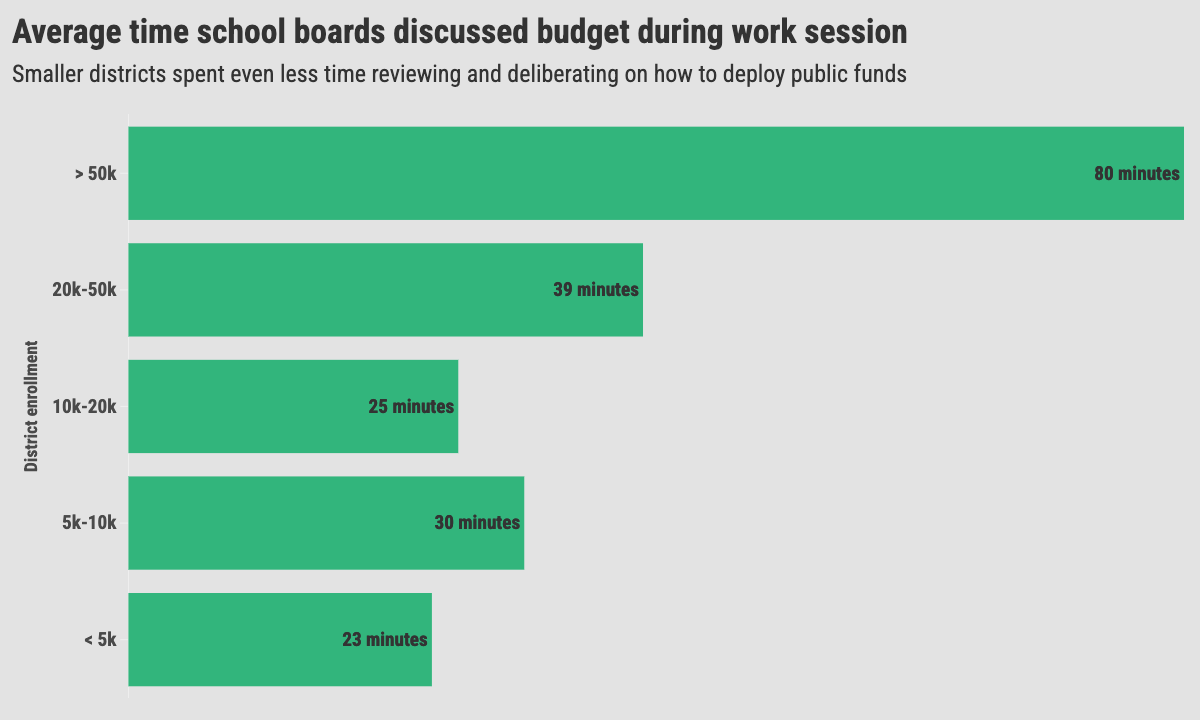

But on average, boards — which typically vote each spring to approve proposed budgets drafted by district leaders — spent just 40 minutes discussing finances. Conversations were longest in the largest school systems, yet in one-third of all boards, they took less than 15 minutes. Fewer than a fourth of budget discussions made reference to the possible impact of past or current spending decisions on student outcomes in reading, math, attendance, mental health measures or assessments.

When board members did ask questions linking spending to results, says Roza, the conversation changed to, “’What did we learn this year and what are we changing next year to accommodate that?’ That that simple statement by a board member would create a lot of pressure on district leaders to be thinking about that and to come ready to talk about that in plain terms.”

Student outcomes were discussed in just 7% of meetings in the highest-poverty districts in the researchers’ sample. Board members asked whether prior investments were delivering their intended effect in just 13% of meetings. How a proposed budget would affect individual schools within a district was raised in 15% of meetings, and the impact on different student demographic groups was discussed 22% of the time.

One-fourth of boards spent the majority of their budget discussions focusing on sources of revenue, which they do not control. In 9 out of 10 meetings, there was no discussion of alternatives to the spending proposal before the board. Researchers categorized 53% of board members as “silent observers,” who sat through meetings without offering substantive comments.

A secondary goal of the research was to determine whether educating board members on evaluating budget trade-offs — something Edunomics does during annual workshops for district leaders and others — has an impact on deliberations. To that end, Edunomics and researchers at the American Institutes of Research’s National Center for Analysis of Longitudinal Data in Education Research, or CALDER, reviewed budget meetings from 2022 and 2023. Half of the videos were from districts where Edunomics had trained board members on finance issues between the two budgeting seasons.

CALDER found that board members who had participated in education finance training were more engaged in budgetary discussions, and were more likely to ask about budget choices and student outcomes and to insist on better information. Board members in high-poverty districts were most likely to ask about the sustainability of financial investments, the impact on different student groups and spending alternatives.

“If we could get more board members focused on whether the budget is delivering the outcomes expected,” says Roza, “that would just send a powerful message that this is what they’re expecting at the next meeting.”

Disclosure: In 2024, Beth Hawkins participated in an Edunomics education finance training.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)