Researchers: Higher Special Education Funding Not Tied to Better Outcomes

Early look at state-by-state spending on special ed reveals scattershot efforts, suggests evidence-backed reading instruction for all kids is crucial.

Get stories like this delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

Updated

An early look at new special education datasets reveals massive inconsistencies in how many children states are identifying as needing services, how much is being spent on them and whether that funding is tied to better outcomes, according to Marguerite Roza, director of Georgetown University’s Edunomics Lab.

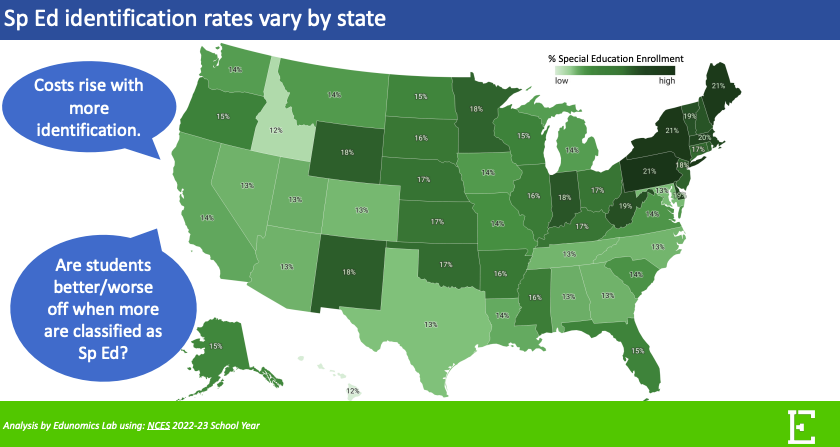

Preliminary though the research is, even the broad takeaways are especially timely, Roza recently told a group of policymakers, educators and journalists. The number of students with disabilities has risen dramatically over the last decade, as has the share of school budgets dedicated to paying for special education.

“Historically, our tendency has been to look the other way on special ed spending,” she said. “It hasn’t gotten the same scrutiny [as] other elements in the district budget.”

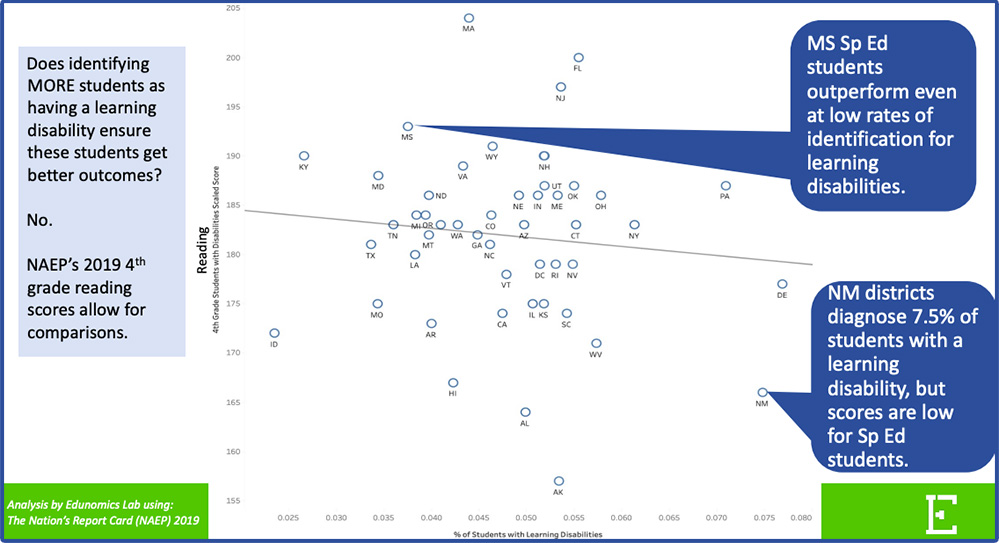

One immediate takeaway is that states that provide sound literacy instruction for all students also post better reading scores for special education students, Roza noted. Case in point: Mississippi, where recent, dramatic gains in literacy have been credited to a 10-year push by state officials to ensure evidence-based reading instruction is taking place in every classroom.

Mississippi is one of two states that dedicated the smallest portion of its education budget — some 8% — to meeting the needs of special education students, yet it is one of four where children with disabilities perform the highest on the reading portion of the National Assessment of Educational Progress.

By contrast, Connecticut spends nearly 22% of its education budget on special education but has middle-of-the-pack reading performance among students with disabilities. More than half of the state’s third graders are reading below grade level, and a new law requiring science-based literacy instruction will not be fully implemented until 2025.

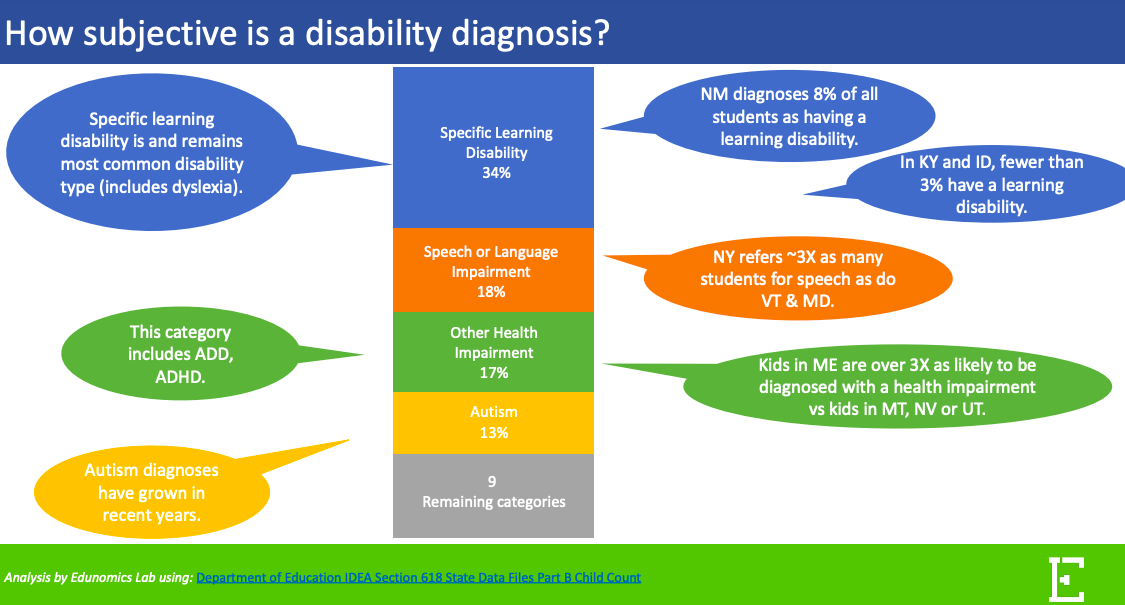

This finding is particularly important because the most common special education diagnosis, specific learning disability, includes children who are dyslexic or who have other neurological differences that interfere with their ability to process language or do math. More than a third of students receiving services fall into this category.

High-quality core literacy instruction could mean fewer students who need an individualized education program — a federally mandated plan that spells out how a child with a disability will be served. Other research has shown that struggling readers whose needs are identified early are less likely to need intensive support in later grades.

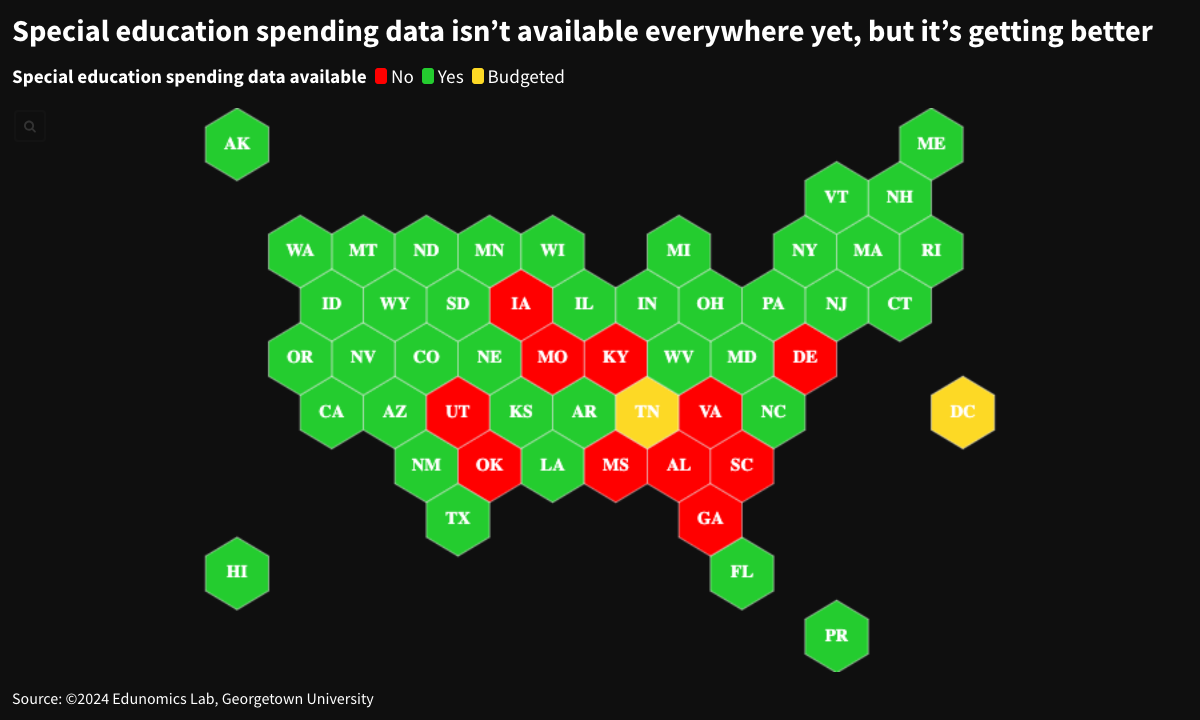

In the 2019-20 school year, the National Center for Education Statistics, part of the U.S. Department of Education’s research arm, began collecting data compiled by states on district-level special education spending. A number of states have yet to provide any information, but Edunomics researchers were able to combine the first two years of information with existing records to begin building an overview.

Between the 2013-14 and 2022-23 school years, the number of children in special education rose from 6.5 million to 7.5 million, even as public school enrollment fell by more than 400,000. In four Northeastern states — New York, Pennsylvania, Massachusetts and Maine — 1 in 5 students now have an individualized education program, or IEP, while in 11 states, 13% or fewer receive services.

From state to state, diagnoses are wildly inconsistent, raising questions about the subjectivity of how students are funneled into special ed. New Mexico, for example, diagnoses specific learning disabilities in 8% of students, versus less than 3% in Kentucky and Idaho. However, despite identifying a high number of children with learning disorders, New Mexico has some of the lowest literacy rates among special education students in the country.

New York refers almost three times as many children for speech and language services as Vermont and Maryland. Students in Maine are more than three times as likely to be categorized as “other health impairment” — a diagnosis category that includes ADHD — as pupils in Montana, Nevada and Utah.

States also vary wildly in how many special education staffers schools employ, with Ohio and Idaho having less than 20 per 200 students. Hawaii, New York and New Hampshire have three times as many. Yet Hawaii significantly underperforms national averages.

The data also raise questions about the quality of staff delivering services and inequities in how teachers are assigned to schools. Since 2007, the number of special education teachers has risen by 12%, while the number of specialists and paraprofessionals has jumped by 35% and 37%, respectively.

One reason higher staffing levels don’t necessarily correlate to better student outcomes could be that instruction is being delivered by paraprofessionals — often low-skilled, entry-level staff — and not special education teachers.

The data also suggest that the perennial shortage of special educators contributes to inequities in which kids get the most qualified instructors. In Massachusetts — which Edunomics researchers praised for its unusually transparent spending reports — low-poverty schools have higher numbers of licensed special educators. High-poverty schools have fewer teachers and far more paraprofessionals.

Districts often cite federal maintenance-of-effort laws, which put strict guardrails on attempts to lower special education spending, as a reason why they don’t scrutinize the cost-effectiveness of their services. While some of these assumptions are incorrect, more legal flexibility would help, said Roza.

Disclosure: The Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation and the Walton Family Foundation provide financial support to Edunomics Lab and The 74.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)