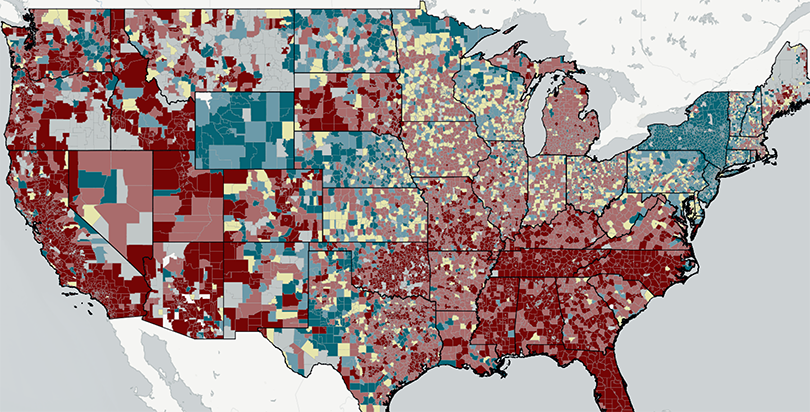

New Map: School Funding Inequality, Often Measured By State, Is Far Worse Nationally Than You Think

School funding inequality isn’t limited to the oft-discussed state-level disparities — in fact, national spending differences paint an even bleaker picture.

A new report published today by the nonprofit group EdBuild shows that inequality between states is even worse than inequality within states. When looking at state and local funding nationally, the poorest districts in the country get 21 percent fewer dollars per student. In a school of 500 students, that’s a gap of nearly $1.5 million between the schools poor and wealthy students attend.

“What we found is that there are dramatic differences [in spending] that point to a completely arbitrary system,” said Rebecca Sibilia, EdBuild’s CEO and founder.

Below is a scatterplot that EdBuild released to The 74, showing that on average as poverty went up, state and local funding went down.

Virtually every state in the country has experienced a school funding lawsuit arguing that the way education is funded within the state isn’t adequate, fair or both. Some have been successful; others haven’t. Many still have suits making their way through court.

A variety of studies have documented that some states — think Nevada, New York, Pennsylvania, and Illinois, among others — spend the least on poor students. A report released earlier this month by EdBuild echoed these findings, showing regressive school funding systems in many places. According to EdBuild, the average state spends about 5 percent less per pupil on poor kids compared to wealthier ones in the same state.

The latest study, though, emphasizes something seemingly paradoxical: Funding inequality nationally is worse overall than even the most unequal state. How could that be though? How could the total disparity across 50 states be worse than any individual one?

Sibilia explains: “In states that do have a high number of students in concentrated poverty… they’re funding all education at a lower level than states that have a lesser number of students in concentrated poverty.” In other words, if you look at the states with the highest poverty rates — mostly Southern states — they also spend the least money on education. (This may stem, at least in part, from less wealthy states simply having less money to spend on education.)

Click here to view the interactive map

This highlights the fact that there can be — and often are — funding inequities in every part of the system: at the national, state, and local levels.

(EdBuild’s numbers do not include federal dollars — which account for only about 9 percent of total education spending — because the idea behind some of that money is to give lower-income students an extra boost, rather than to make up for existing inequities. That philosophy, by the way, is where the phrase ‘supplement not supplant’ comes from — right now a point of major controversy in Congress over how to ensure federal money is targeted to poor students.)

Bruce Baker, a professor at Rutgers University who reviewed EdBuild’s findings, said he had disagreements with the methodology, saying it’s inevitably challenging to make apples-to-apples funding comparisons across the whole nation. “If we’re evaluating equity, we want to be looking at the real resources kids receive in say, Arizona versus New York … To buy the same quantities of the same stuff in Arizona and New York has a very different cost.” EdBuild adjusts for cost-of-living in different parts of the country, though Baker had some methodological concerns about their approach.

Still, Baker said the basic findings reflected in EdBuild’s data hold up: “That storyline is absolutely is true… The extremes nationally are certainly probably worse than the extremes within most states.” In some high-poverty states, it’s not that poor districts get less; it’s that funding is bad across the board or “equitably awful” as Baker puts it.

The numbers paint a depressing picture of resource inequality, but even more disheartening perhaps are the political hurdles awaiting policymakers who want to address the issue. Both Baker and Sibilia agreed that correcting these funding inequalities would be a tough sell politically.

Since the problem is a national one, the most efficient solution would seem to come from the federal government. But — in our highly decentralized education system and with the new Every Student Succeeds Act weakening federal oversight — the only approach would be to withhold money from certain states who don’t correct their inequities. That course of action, however, risks making the problem worse in states willing to turn down federal money that comes with strings attached. Baker said that the states most likely to defy the feds (and lose out on free money) are probably the same ones that are already underfunding their schools.

In the report, EdBuild is critical of a 1973 Supreme Court decision, San Antonio v. Rodriguez, limiting students’ ability to sue over school funding disparities. “The San Antonio ruling means that, even though the federal government provides approximately 9% of total education revenue, it has little role in addressing the inconsistencies and inequities in education funding,” the study states.

Of course, a crucial question here is how school funding connects with student performance. Some argue that money is not a consistent driver of student outcomes, while others claim that resources are a critical part of educational quality.

A significant body of recent research suggests that, on average, putting more money into schools leads to better student outcomes.

Sibilia agrees: “Money absolutely matters… Money influences how a school can recruit and retain teachers, it influences what kind of extracurriculars you can provide to students, it influences the dropout prevention programs you can run in concentrated poverty areas, it influences how much money you have to transport kids in rural areas — it influences everything.”

Disclosures: The 74 and EdBuild are both funded by the Walton and the Buck foundations. In 2012, I was an intern at StudentsFirst at the same time that EdBuild’s Sibilia worked there, though I never worked with her directly.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)